🎧🍌 The Peel Episode 1: Building McDonald's for the Next Generation | Jonathan Neman, Co-founder and CEO of Sweetgreen

Sweetgreen's origin story, the $2 trillion of hidden external costs in the US food system, building an enduring brand, and never giving up

Hi everyone 👋 Turner back again with The Split. Welcome to all new readers and the 22,000+ of you tuning in to each email!

This is a special week of The Split with three episodes of my new podcast The Peel releasing this Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday (beginning next week, we’ll release one per week). This is also the first post with extra benefits for Premium subscribers, human edited and enriched podcast transcripts (these will get better!).

👉 To jump right in, find Episode #1 on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and YouTube.

The Peel will explore the world’s greatest startup stories, where we’ll:

Get a behind the scenes look into each company’s origin story

Explore how the industries they operate in actually work, and

Learn playbooks and tactics you can use to launch and scale your own business

Upcoming guests include the founders of Mercury, Superhuman, Overtime, Slice, Primer, Forward, Snackpass, Haystack, and more.

I’m still figuring out how this podcasting thing works, please let me know if you have any feedback on this first episode or suggestions for future guests!

If you want to support the show, I’d love it if you could leave a review wherever you listen to podcasts, like, comment, and subscribe if you’re watching on YouTube, and share it with one friend who might like this episode. It helps with visibility and getting more guests, and it takes less than two minutes.

And now, on to The Peel Episode #1 with Jonathan Neman, Co-founder and CEO of Sweetgreen.

Building McDonald's for the Next Generation | Jonathan Neman, Co-founder and CEO of Sweetgreen

👉 Find the episode on Spotify, Apple, and YouTube. 👈

Jonathan Neman is Co-Founder & CEO of Sweetgreen, an American fast casual restaurant chain that serves salads. Jonathan and his co-founders started the company in 2007, opening their first restaurant just three months out of college. Sweetgreen opened its second and third locations in the middle of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, and went public in 2021 in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sweetgreen’s focus on locally sourced quality ingredients has built it into a national brand with more than 200 restaurants across the US.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter and LinkedIn.

This episode is brought to you by Secureframe, the automated compliance platform built by compliance experts. Book a demo here.

To inquire on sponsorship opportunities on future episodes, click here.

In this episode, we discuss:

How the restaurant industry actually works

The $2 trillion indirect healthcare and environmental costs of the US food system

Sweetgreen’s origin story

How the 2nd location almost failed

Launching a music festival headlined by Kendrick Lamar, The Weeknd, and The Strokes

Killing a major product line to double down on online ordering in 2015

How to build an enduring brand

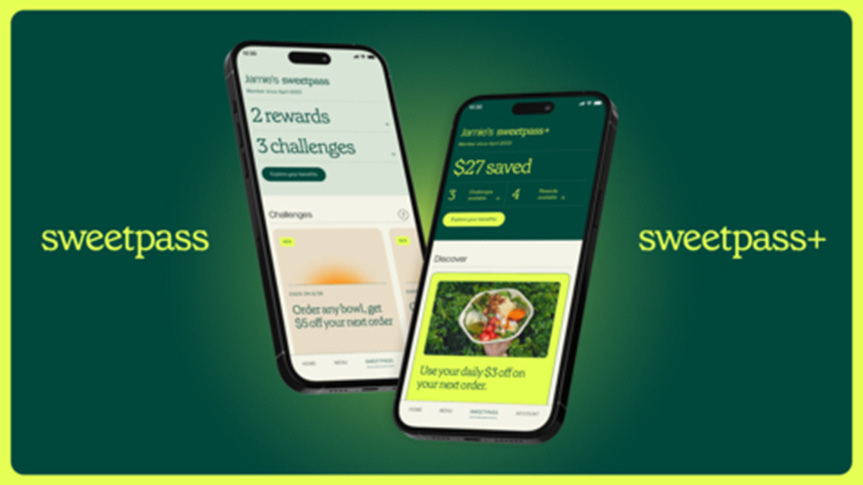

Sweetgreen’s new salad subscription and gamified loyalty program

The surprising benefits of Sweetgreen’s new automated Infinite Kitchen

Why the best entrepreneurs never give up

Follow The Peel on Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok.

Thank you to Zac and Xavier at Supermix for the help with production and distribution!

👉 Find the full episode on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and YouTube 👈

Transcript

Find transcripts of all prior episodes here.

Turner: Jonathan, how's it going? Thanks for joining me today!

Jonathan: Thank you so much for having me. It's great to be here!

Turner: I wanted to jump right in. Could you talk a little bit about the state of the restaurant industry, big current topics and trends, and how it all works?

Jonathan: I can talk a little bit about what we saw when we started and then maybe what's changed 15 years later. So going back to 2007 when we started the company, we wanted a healthy option that was delicious, affordable, and convenient in our own community. We were students at Georgetown and we couldn't find a place to eat and we just looked around, we're like, “This is crazy. How come there is nowhere to eat that is healthy but also delicious?” And you looked around at all the brands and things like McDonald's or Coca-Cola or Subway - the best option for healthy food was considered Subway, which is full of processed foods. They promote this idea of freshness, but it’s really not that healthy, similar to McDonald's and all the other food out there.

The system is really focused on most efficiently moving calories, largely processed, and getting them to people in the most efficient way as possible. And in the effort to standardize things and drive margins, as well as the fact that most restaurants are franchised in this country, it means that you really have to build a system that dumbs down the operation at the edges, which means most of the food is actually prepared further upstream, somewhere in a commissary, really in a factory. And then it's kinda reheated for you.

Turner: Which is terrible.

Jonathan: It's crazy when you think about how it's being done. In 2007, Chipotle had recently gone public, so you saw a different kind of model being developed around fast casual, and they had a fresher model of food and still maybe not that healthy, but definitely fresher. And we saw an opportunity to create, what we thought could be, one day, a global iconic brand that stood for food that was healthy and delicious and really supported the communities that we were in.

So that was the idea from the beginning: how do we create the McDonald's of our generation? The industry - first of all, it's a huge industry. I think the number I recently saw was 200,000 fast food restaurants in the United States. So that's one for every 200 people.

Turner: When you say fast food, how is that defined?

Jonathan: So call it the McDonald's. We probably would not be in that category – we’re in this hybrid category of fast casual or fine casual. A lot of people define it differently – still fast, but with a higher quality of food.

By the way, I don't mind calling us fast food and going head-to-head with them because I think you’re speaking about the experience, not about the quality of food.

You have about 200,000 fast food restaurants in the US. Most of them are franchised. So if you think about the big restaurant operators in in the country, all of them are franchises or some hybrid version of the franchise model. McDonald's is pretty much fully franchised. Yum![1], they own Taco Bell. Restaurant Brands owns Burger King, Popeyes, Tim Hortons. All these companies are franchise. You have a few operators that are not franchised - Chipotle being one. You have Chick-fil-A, which is a bit of a hybrid model. In-N-Out is another that is not franchised. Starbucks is largely not franchised.

[1] Yum! Brands is a restaurant company that owns quick-service chains Taco Bell, Pizza Hut and KFC. They spun out from PepsiCo’s fast food division.

But for the most part, think about restaurant companies not as actually running the restaurants. They are the brand, the marketing engine, behind these restaurants, but really are making something like a 5% franchise fee off these other operators. Sometimes they’re more mom and pop; sometimes they’re larger franchise groups that are running hundreds or thousands of restaurants.

COVID changed our industry significantly. One - obviously digital has shifted significantly. Restaurants were kind of late to the game as it relates to digital. I think that's one of the things that Sweetgreen did differently. We were early to digital and our digital penetration was over 50% before the pandemic. Obviously, like anything else in e-commerce, the pandemic brought that forward for a lot of people. All the big chains now are seeing digital penetration somewhere around 30 to 40% of total sales.

Another big shift that we're seeing is around labor. The restaurant industry employs a lot of people. A lot of people left the workforce during the pandemic and it's a job you cannot do remotely. Today, there are over 2 million open jobs in the restaurant industry. So whatever you think is going on with our economy, the restaurant industry is still hiring. We did see that the industry's seen over 20% inflation from wages so the average wage for restaurant employees has gone up significantly.

Turner: Do you know why there's that huge gap? Because I feel like the narrative I hear is “Gen Z doesn't want to work.” Is that true or what's driving it?

Full episode available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and YouTube.

Jonathan: I think it's a job that you can't do behind a computer. It’s a job you largely have to do with your hands and it's a hospitality job and I think those can come with a lot of stress and pressure. I do think what's amazing about the restaurant industry is, it's one of the only places where you can come work really without a lot of preexisting qualifications. So like you can come work at Sweetgreen as a team member and within three years be a head coach, what we call our GM, making over a hundred thousand dollars a year. So, I think that's one of the amazing things - is the development opportunity and the leadership opportunity that, whether it's Sweetgreen or other restaurants, really provides.

I make fun of McDonald's a lot - we kind of use them as a foil to a lot of what we do, and I think the food they serve does make our country sick. However, if you look at their commercials and what they talk about, it's about the jobs they create.

Turner: Yeah, I guess when you kind of think about how the country's evolved, like even going back to Ford - I think Ford was kind of known for employing a ton of people and his goal was to make the cars affordable for all the employees. Do you know what percentage of people in the country work in restaurants or what percentage it employs?

Jonathan: I think you have tens of millions of people working in the restaurant industry. I believe it's probably (one of) the top two employers in the country. When we founded the company and you looked around at the food system - so much has changed since 15 years ago - I think when we were like, “Oh, we're starting this healthy food concept. We're gonna sell salads.” People were like, “Well, alright, you're gonna get to 10 stores and you're gonna -

Turner: Go bankrupt. No one's gonna buy 'em.

Jonathan: - get one store in every major market and that's kinda it.” Today we have over 200 restaurants and we believe the TAM is in the thousands. And it's one of those things that as we build the company, I think the TAM - the addressable market - continues to expand as we grow.

I remember Whole Foods early on when their original goal was 50 (stores). When they got to 50, they were like, maybe we can have 100. When they got to 100, they were like, maybe we can have 200. Whole Foods has 600 Whole Foods today. If you think about, a company like Lululemon - it has over 500 retail stores in the US. So I think the consumer is really beginning to value health and wellness a lot more.

The system, however, has not caught up to it largely because, I think, a lot of it has to do with the economics of the restaurant business. It is very hard to make money. It is capital intensive to build a restaurant. There's then a heavy labor component. There's a heavy cost of goods component or rent component, etc., so you need to be good at a lot of things to turn a profit in the industry.

And the incentives in the US are highly, highly misaligned towards healthier outcomes. So, you know, 97% of the subsidies in the US goes towards, five crops that are not the crops that you want to be eating. So most of our subsidies are going to things like corn. And when I say corn, it's not corn like corn on the cob, it's corn that creates high fructose corn syrup.

Turner: Which is - what's high Fucose corn syrup? For people who don't know.

Jonathan: It's highly refined processed sugar. It's what goes in Coca-Cola and it's just really not good for you. You'd be surprised how much high fructose corn syrup is in everything. I do believe it's one of the biggest, issues facing us as a country - the health of the country that's honestly been exacerbated by the pandemic.

The fact that we are so unhealthy has a lot to do with the food system. And the cost, the financial burden, on the country is huge. Rockefeller came out with a report a couple years ago that showed that the cost of the food system, the externalities, are about $2 trillion dollars. A trillion of it is on health outcomes, another trillion is on the environment and climate. And so this just has massive ramifications, but it's such a fragmented industry.

Another report just came out that showed the top 10 restaurants gained market share - they went from like 23% of the total market to like 28%. The 10 biggest are only controlling less than 30% of the overall system.

Turner: Are there any such thing as like local monopolies, like certain brands or certain restaurants might have control of certain demographics or regions, and does that impact things at all?

Jonathan: Yeah, I think that's the other thing that's really interesting in the restaurant business. There's a lot of national brands, but it’s a city by city, community by community business. So, here in California, In-N-Out is truly beloved, but they only have a few hundred locations. You go to the South and people love Whataburger. You go to Canada, people love Tim Horton's. A lot of different brands really work in certain regions but really haven't transcended to become national. And one of the things that we did very early on, was we always intended to be a national and then, one day, global brand.

And so, we started the company in DC. We opened the first almost 20 restaurants in the greater DC area. We really thought it was important in order to support the supply chain and to build a brand locally that we stayed in one area. But from there, we intentionally branched out. We went to Boston, Philly, New York, Chicago, San Francisco, LA, and Austin. We went to the major cities with the intention of building a national brand. We want to have a national presence and we want to plant flags in these different places. We don't go to cities and just plant one. We'll go and we'll at least open a few stores in a city and look to build a network. Our goal has always been to build a national brand.

Turner: And I'm assuming each new store in a market, up to a point of saturation, just probably improves margins across the board for each store, right?

Jonathan: Correct, yeah. They help acquire new customers. We buy a lot of food locally, so that helps us a lot. So the more stores we have in a single market, the more we're able to see some economies of scale at the local level from a food cost perspective and around management and overhead. You have one person that can oversee 8 to 10 stores in a market. And so if you open one store, you’re (only) leveraging that person across one store, versus you can grow that to 8 to 10 and you still have that one person overseeing it. We also see a lot of efficiencies in marketing. Once you hit a certain scale, you're able to invest into marketing at the local level that can improve the economics overall.

Turner: You could basically have done everything differently. You’re almost thinking first principles: what's best for, maybe for the business, maybe for society too. Can you talk about how you guys started the first store?

Jonathan: Yeah, of course. So I went to school in Georgetown, Washington, DC and I met my two co-founders, and I think we, the three of us, all bonded with just this entrepreneurial itch. We all somehow knew we wanted to be entrepreneurs and we were always like the three friends that we're talking about starting a business.

Turner: Did you do anything before Sweetgreen? Any ideas or failed concepts?

Jonathan: A ton of ideas. I had a concept in high school. I ran a actually a club called the Young Entrepreneurs Club, where, as our business, we started selling planners like agenda books.

Turner: To run your business on?

Jonathan: No to students. And what’s interesting is we had an interesting way of doing it. I went to a pretty big high school. I think there were like 5,000 kids in the school. And so what we did was we said, “Hey, we have a distribution of 5,000 kids.” We made it. We figured out how to make it almost mandatory for everyone to have one of these agenda books. It just became like part of the curriculum. We convinced the teachers and the administration to make it standard so we sold them almost at cost. But then we went to advertisers locally, and we said, “Hey, we have 5,000 kids here.” This is before Facebook, really before digital. “We have access to 5,000 eyeballs of these kids that you want to get.” And we would sell ads in the book and we figured out we could sell ads on the back cover on the corner of each page. We figured out really clever ways to sell ads on these agenda books. Each year we would do it would generate over $30 - $40,000, in ad revenue.

Turner: Wow. And that was pure profit, right?

Jonathan: It was pure profit. There was really, you know, there was nothing. So that was one early concept. I had a lot of early tutoring and teaching kids how to play basketball - always had some sort of side hustle.

I think it really came from watching my parents. My parents came here in 1979. They were immigrants from Iran. They came over after the revolution and they really had to start over here. They had to leave everything in the middle of the night, leave all their belongings, just move to the United States, and start over. And I got to watch my dad do that with his two brothers and kind of live the American dream. And for me it was always this idea of starting something from scratch and building something. From the time I was a kid, I remember I used to read biographies of business people and always looked up to these other great business leaders and always imagined some creating some sort of company. I never thought it would be in food. My partners were similar. Both my partners, my co-founders - their parents were also immigrants to this country. So we kind bonded over that as well.

So, fast-forward senior year, we'd all gone abroad. I had gone abroad in Australia, this is 2005 or 2006. I'm in Sydney. And what was so interesting is the cool places to eat - the places you kind of like would want to go, the cool cafes on the beach - were all really healthy. And it was cool to be healthy, cool to have this active lifestyle, and the cool kids were eating salads and bowls and riding bikes and skateboarding and surfing. And I was like, wow, this is a very cool lifestyle - this idea of being healthy, taking care of yourself so you can be active and have fun.

Turner: Which is not what it was like here in the US.

Jonathan: It was not that all. We were like, wow, there’s something really here. And then it took my love of food and love of business - and luckily I met these two co-founders - we all complimented each other really well, we still work together, and we decided to start a restaurant. And so right in the fall of senior year, we said, “Hey, wouldn't it be cool if this just existed here? Isn't it crazy that there's not a decent place to eat and our options are, Subway, McDonald's, Chipotle? Like there's not like a clean, good, healthy place to eat?”

Turner: Were there any big salad chains at the time?

Jonathan: No, there were no real salad chains yet. You had the ones in New York that were kind of like the Cafe Europas, things like that.

Turner: $30 salads or something?

Jonathan: Yeah, but it really hadn't become much of a thing yet. And for us, it's funny because people were like, “Why salads?”. Part of it was because it was naturally healthy and part of it was that none of us had any culinary background but we could figure out how to make salads in the early days.

Turner: Just throw leaves in a bowl!

Jonathan: It's true till today – a good salad is all about the sourcing of the ingredients. I actually believe great food in general. You talk to any great chef, they give all the credit to the growers. You know, our chef Amos would always be like, “Listen, I, all I did is not mess this thing up. Right? I bought the best food and my job was to let the ingredients shine.” And the salad is kind of this format that really does let the quality of the ingredients shine. And that's kind of been the thing from the beginning, is source the best food and just kind of don't mess it up. Create cool combinations for it, make healthy food more comforting, meet customers where they are, make it easier for them so it's delicious - it has a brand that people believe in. It's a great, convenient experience and meets customers where they are.

And so we decided to open the first restaurant. We raised money from friends and family. This is before VC had totally taken off and it was easier to raise money, probably more like what it's today. And for restaurants at the time, it was especially hard to raise money. So we raised $300,000 from about 50 investors. So, if you do the math, it's like almost $5,000 per person. It was classmates, it was old bosses that we had interned for, it was really anyone you know. We met someone on a plane that we convinced, like anyone that would take a meeting. We had to talk to hundreds and hundreds of people. The amount of times we heard why a restaurant business is so bad, why 90% fail in the first year, all of these things - we heard over and over.

Turner: So my wife has wanted to start a restaurant. She actually has a similar story where we ate at a really nice cafe in the UK and she was like, I want to build this in the US. And for the last 10 years I've been like, restaurants are very, very bad businesses - let's wait a little bit if you really want to start something. How did you convince people?

Jonathan: I think at the, at the time it was people just believing in us. It was friends that we knew or old bosses, and they were like, “Alright, five grand, I'll take a bet. I believe in you guys. It seems like a different approach in what you're doing, and either this goes to nothing, or this can be something that is potentially really, really big.”

Turner: Yeah, and I guess there's probably a cash flow component too. Like, did you give out dividends or anything like that?

Jonathan: So when we started, you weren't investing in Sweetgreen Inc., you were investing in Sweetgreen Georgetown. And so there was a management company that held the IP and then you were investing in the individual entity and we were giving quarterly distributions. We actually paid back our investors in our first restaurant with cash before we eventually, after we had three restaurants, decided we were gonna continue opening. We rolled up all of the entities into a singular entity. We traded everyone being like, “Hey, you own X percent of restaurant one and X percent of restaurant two and X percent of restaurant three. We're gonna give you a different percentage in the overall holding.”

Turner: How many meetings did you say it took?

Jonathan: Hundreds. And I always say with raising money - the value is, it's kind of like going through this gauntlet of really sharpening your thinking and your will. It takes a level of relentlessness of having to do that and tell your story so many times and try to convince so many people. And in the process, you kind of convince yourself too, like you have to believe it so much to go through that pain of how many meetings and how many rejections that you really have to believe it and it really forces you to sharpen your thinking.

Turner: So you got the round done, the first 300,000, you own the restaurant. How did it go?

Jonathan: So we thought we'd open in the spring of 2007 while we were still students and we thought it was just going to be maybe like a one-and-done. We were like, “We'll open one and we'll hire someone to run it and we'll all go on with our lives. Maybe they'll grow it and like, great, it'll be a fun experiment. We'll learn a ton and it'll be a great value to the community.” It turns out what we thought opening a restaurant was, and what it ended up being, was very different. From the outside, it looked super simple. It looked like you go buy a bunch of kitchen equipment and put it in an empty box and you buy these ingredients and you just kind of make them and serve people.

Turner: Yeah. People just show up and buy them.

Jonathan: Yeah, starting a business is really hard. Everything from like setting up, and for us, building restaurants is really hard. It's not just buying kitchen equipment.

Turner: Yeah. Cause you guys kind of have a, at least at the time, sort of unique setup for things.

Jonathan: I think you just talked about first principles. A lot of the credit I give was this naivete. We actually just didn't know shit, so we didn't know how the restaurant industry worked. And so we kinda thought, oh, how should it work? Oh, we go to the farmer's market, why don't we go to the farmers and talk to them about buying food directly? We didn't know that people didn't make their food in the restaurant themselves. What else do you do but make it all from scratch? And so there's all these simple concepts that seem obvious and I think are part of our model, but it’s not how the restaurant industry was set up.

And I think as we started writing the business plan, we started to have early inkling like whoa, this is actually a big problem. This is not a problem just in Georgetown in our little community - this is a big opportunity. Fast casual was a really fast-growing market at the time. It seemed like there was a real niche to be served around people that wanted healthy and delicious food together.

And so we ended up opening August 1st, 2007, first restaurant was only 500 square feet, so it was tiny. Just give you an idea, our restaurants today are between 2,500 to 3,000 square feet, so five or six times the size. In that store, we still did all the scratch cooking. We did everything that we do today so it had to be done in a tiny, tiny store. And I think some of the advantages is it forced us - the constraint for was really helpful. I always believe that constraint drives creativity. And so it forced us to keep things really simple and distill the concept down to the basics.

(The original Sweetgreen location on M Street NW in Washington, D.C.)

I think if we had a bigger space day one, we would've probably done sandwiches and smoothies and God knows what else we would've had on the menu. But you only have 500 feet. You had to really, really keep it simple.

I think we were very lucky from the very beginning. Even from the very first day we opened the doors and it was very clear that we'd filled a need in the community. People really were looking for an option. And by the time students were back in September you know, the restaurant was doing really well. We couldn't keep up with the business until winter hit and the students went away for school and we had no seating inside and people didn't really want to eat salads in the winter. And all of a sudden our sales were down like 70% from what they were.

Turner: Wow. What, like what were your investors doing? How did they handle it?

Jonathan: I mean, it was very scary for all of us because it's not like we like ran with working capital in the business. At the end of the first restaurant, we raised enough money to build the restaurant and we still owed the contractor like a hundred grand.

Turner: Oh wow. So you were selling salads and it was just going to the contractor?

Jonathan: Yeah, we were literally still paying the contractor. We had no working capital. We were the employees in the restaurant for the most part. We had a couple other people, but we were just running the place for, for the first few months. And it was very, very scary.

Turner: You had committed to go work somewhere before this all happened and you actually went and worked there for a while. How did that go?

Jonathan: Yeah, that was also a really interesting part of my life story. So we started writing the business plan call it September, October of that year in 2006. Right around the same time, at least at our school, they started recruiting for jobs. And at Georgetown, everybody would go into consulting and banking. I knew I didn't want to be a banker, but consulting sounded interesting. You got to work on business strategy. So applied for a job and at the time, I thought it was my dream job to go work at Bain. And I got the job and they gave me a signing bonus.

Turner: Which is awesome when you're in college.

Jonathan: I put all that money in Apple in 2006. I still haven't sold it, which was the best investment I ever made. But I said I'd be in Bain in Boston the following October. I almost forgot about it and went on with my life. I started the business, figured I'd figure it out later. We opened the restaurant and Bain was like, “All right, are you ready to come?”. And I'm like, “I'm actually not ready. Can we delay it a little bit?” And so we pushed it out till around the end of the year.

By the end of the year, that winter, I worked at Bain. I had a great experience there. I learned a ton and met a ton of really high-quality people. I learned a lot about a lot of the basics and fundamentals around business strategy. But at the end of the day, I also learned that I wanted to be driving the business, not advising the business. And the frustration of just making decks and not actually solving the problem was just maddening to me.

I remember one of my first days I got a case for some telecom company and our job was to reduce churn. I'm like, “Well, why don't we go think about what's wrong with the product? Why are people churning so fast?” And they were like, “No, our job is to figure out what's the right win-back offer when they call to cancel and make the telephone decision tree-”

Turner: What?!

Jonathan: “-How much should I give them when they call to cancel? Do I give them one free month to stay or six free months? And what's the LTV of like doing that?” I'm like, “You guys are just trying to stop the bleeding here. This is not very sustainable.”

Turner: Which is terrible for the brand. I don't know who you're talking about, but my internet provider - trying to communicate with them - part of their strategy is to make it hard to even modify your subscription or your account.

Jonathan: Yeah. And I get why people do this from a business sense, but as an entrepreneur, I always wanted to go to the core issue. What's wrong with the product? What's wrong with the experience? What's up with the brand? What's up with the team and the org structure? Like where do we go to the heart of the problem?

And I think having already started a business that I was emotionally connected to and starting to be successful, I was always one foot in, one foot out. And so after six or eight months, we decided we were gonna open a second and third restaurant and so I decided to move back.

Turner: How did that second restaurant go?

Jonathan: So we decided to open a second and third restaurant, pretty much at the same time. So now we're looking at early 2009. The economy is a disaster. We’re fully in the great financial crisis. We had watched Lehman Brothers happen and AIG and just these crazy moments, which in retrospect, are even crazier. At the time, you didn't even understand that it was crazy because it felt like you just were born into that world. We didn't know how bad the economy was because that's all we knew.

And we opened, so we raised a lot more money for restaurant two and three. Restaurant three was really successful. We opened in the same month. It was in Bethesda, Maryland, and right out the gates, it was great. But restaurant two we opened in DuPont Circle in DC, and it was not successful. We opened in April, we spent over two times what we spent on the first restaurant. We spent like $700,000 building it, it was supposed to be this big flagship for us. And we opened the doors and pretty much had no customers, We were doing way less than we were doing at our first restaurant and this restaurant was bigger and was supposed to do way more.

We just realized people didn't know who we were. At the first Georgetown restaurant, people knew who we were because it was the story of the students opening this restaurant and we had a very captive audience. In DuPont we didn't have that. But what we did have is we had the farmer's market behind our parking lot of that restaurant. And so we knew the customers were there. And this is not just any farmer's market, this is THE farmer's market of DC. It's kinda like the Union Square Farmer's Market in New York. It's like the major farmer's market. And so realized there was an opportunity to capture some attention.

And again, not knowing what we didn't know, our idea as 23-year-old kids was, “Why don't we go buy a big speaker from Guitar Center, get a big folding table and just start playing music.” And the funny story was at the very early days, our menu was made out of this wildflower seeded paper. It was printed on this seeded paper as like a sustainability thing and the whole idea was like, come get the menus and plant the menu.

Turner: It would actually grow into something?

Jonathan: It would actually grow! It was kind if this gimmicky thing while we were playing music and just meeting the community and giving out samples. It's interesting - we still have this same challenge. People think of Sweetgreen and they're like, “Oh, it's a salad place, I'm not a salad guy. That doesn't sound delicious. That's a side, that's an appetizer. That's not a meal. That's not gonna fill me up.” And we knew we just had to get people to try it because how we build salad and bowls is different than I think how most people think about it.

And so we started DJing. This little DJ set turned into a block party. The block party grew and grew, and all of a sudden few months later, we have over a thousand people there with a bunch of local artists and bands having this block party for Sweetgreen. It was right after the farmer's market. And we realized there was an opportunity to really elevate the brand beyond just a restaurant and build in more lifestyle components that - back to like the founding vision of it - eating healthy is just part of a greater healthy lifestyle and it can still be fun and cool.

And music was a passion of ours and, we thought, a great universal language to share with people and connect on. And so we turned that block party into a music festival, and it went from like a thousand people in a parking lot to the next year with 25,000 people at Merriweather Post Pavilion. It was headlined by the Strokes – here’s a poster in 2015 you can see.

Turner: Oh wow! For people who are just listening and don't have video, there's like avocados. It looks like you have peas, different fish, and then there's also musical instruments like a guitar.

Jonathan: And then the artists are Kendrick Lamar, Calvin Harris, The Weeknd, Pixies, Billy Idol, Tove Lo, Marina and the Diamonds, SZA. So I think it was this like cool way of bringing these huge artists and creating this amazing experience telling the story of our brand that “Hey, you can listen to music and go to this big music festival and still be healthy.”

Turner: Okay, so I have to ask, how did you convince those people to come and perform at a music festival for a salad chain? Had any of them even heard of Sweetgreen before?

Jonathan: No one had heard of it for a long time. The festival had bigger brand recognition because we ran the festival for like six or seven years. It was kind of the big festival in the DC area. We had a great partner that we worked with there that owns 930 Club and a bunch of other venues. So he would help us with a lot of the booking. And two of our early investors were the guys that started The FADER[2] magazine, John Cohen and Rob Stone, and they were very helpful in the early days of helping us think about how to build the lifestyle brand and then they had a lot of connections in music. And so, I always remember, the first one when we decided we were gonna do a festival, we wrote a list of bands. It was like, Daft Punk, Jay-Z - we named all these big bands. The Strokes were always one of my favorite bands so we had them on the list, and someone knew The Strokes’ manager. They were coming, doing a comeback tour and we sent him an offer and they said yes. And it was just like, whoa, this thing's real.

[2] FADER is a NYC based magazine launched in 1999, covering music, style and culture. It was the first print publication to be released on iTunes.

Turner: Were you able to fund the music festival? Like did people pay to get in or were you kind of running it as a loss and hoping that people came to the restaurant?

Jonathan: The festival could not run at a loss because again, at the time we were not funded. We would raise enough money to open a restaurant and that was really it. And you had years where the festival, for the most part, broke even. You had years where you made a little bit of money. You had years where you lost a little bit of money. But for the most part, the goal was to kind of break even and have this amazing moment of telling our brand story. So we got a lot content out of it. We got a lot of earned media out of it, and I think it just kind of positioned the brand in a different way.

Turner: And then also leveraging the cap table, were you thinking about that when you raised money from those guys? That they'd help us down the road?

Jonathan: Kind of. I think for us, we really valued relationships and looked for people that we admired and wanted advice from and would somehow convince them to give us a little bit of money and leverage their expertise. So one of the secrets to success very early on is, we did a lot of networking outreach and met a lot of people who we could learn from, whether it be a guy named Walter Rob, who was the co-CEO of Whole Foods for a long time - he joined early; a guy named, Gary Hirschberg, who is this founder of Stonyfield Yogurt, kinda one of the OG pioneers of the natural food movement – he joined; Seth Goldman, who did Honest Tea. So we had some people in the natural food world that were involved, and then we had other people, more lifestyle types, and our job was to synthesize all those relationships and see how they could help us.

Turner: And you mentioned frozen yogurt. That was a big category initially, right?

Jonathan: Yeah. When we first opened, it was a huge part of the business.

(Sweetgreen’s original frozen yogurt called Sweetflow)

Turner: I think you mentioned it was something like 30% of revenue, 50% transactions, and then you killed it. Like what? That seems like an insane idea.

Jonathan: Take your mind back to 2007, it was when that frozen yogurt craze was taking over the country. Pinkberry, Red Mango - they were starting to grow, but it wasn't a huge thing yet. When we opened in DC and we had that type of tart frozen yogurt, we were the first to market. When we opened Georgetown, it was the only place you could get that type of product. By the time we got rid of it in 2013, it was a product that had really been commoditized. You had thousands of these yogurt shops everywhere and it went from being 30% of our sales to probably mid-single digits of sales, which at the time we were like, “Okay, this is great,” BUT we had this idea around online ordering and now we have these huge lines. We had just opened in New York City we have this line around the corner, and we can only go as fast as this one make line can produce.

Turner: So was it like a 50/50 split? Half the restaurant was salad, half was froyo?

Jonathan: Not half, but it took up a pretty good chunk of space, especially in those restaurants where like you had the yogurt machine. You had all the toppings for it. We had this idea around online ordering - instead of having a yogurt machine there, we can put another make line. We can put these shelves up to have people do online ordering. So by 2010, we had been playing with online ordering, which I remember at the time, people thought we were crazy. People aren't gonna order on their phone…

Turner: (Sarcastic) Yeah that's ridiculous. Why would you do that?

Jonathan: Why would you do that? But it's interesting, the iPhone came out in 2007, the same year as Sweetgreen was founded. And I think we were just very lucky being of that age, being digitally native in that way, both on social media and on mobile - seeing that that was clearly going to change the world and it was going to change e-commerce in a significant way.

And so at the time, the yogurt was probably, mid-single digits of our business, but we saw the opportunity with online ordering and mobile ordering. We've considered bringing yogurt back because I do think today, now that the market is not saturated, it could be something really great to bring back to capture that like afternoon, day part. And our yogurt was just really, really good. Cause we were able to do it with just great ingredients and not processed, so it had that like tart flavor, but creamy and not processed tasting. But at the end of the day, it was great. We introduced mobile ordering and that ended up being a huge accelerant to the business. We were able to take that line of people, the hundreds of people waiting in line and convert them to mobile customers and essentially double the throughput of each restaurant.

Turner: And then it seems like you've done a lot more around apps, mobile ordering, and also increasing throughput automation, things like that. So recently, you guys had two really big announcements, and this is why I reached out. I was like, “Holy cow, I want to talk about these.” So the salad subscription, Sweetgreen Plus, and then the Infinity Kitchen in Chicago - can you just talk about those and how they work, what the process was like for launching those, what direction you're going with them?

Jonathan: Yeah, of course. I'll talk about, Sweetpass first and then, and then I'll talk a little bit about the Infinite Kitchen. So in terms of Sweetpass - Sweetgreen for a long time had a loyalty program. We had a loyalty program that was more traditional, like buy 10 get one free. We learned that while customers really loved it, it wasn't really driving behavior and it wasn't really driving loyalty. And we thought there was a different way to gamify loyalty and create a membership or subscription model.

I think what positioned us against the competition around this specifically has to do with the food. One of the things that makes Sweetgreen special from an economic standpoint, is the frequency of our guests. Our guests are high frequency users. It's a normal thing for someone to eat Sweetgreen in three times a week, whereas if you look at a lot of our competitors, I don't know if you can say that about a lot of them. The idea was how do you play into these existing behaviors? How do you improve existing behaviors and incentivize things that are people already doing? And just create slight improvements into those things?

We saw a lot of inbound requests around, “Hey, can I just like…subscribe? I don't want to think about it because you can just feed me every single day.” Like how do we make it easier and reduce the friction of just being able to fuel myself with this good nutritious food as often as possible? And so about a year ago we tested into this program and we called it Sweetpass, where for $10 a month you get some sort of discount. And so we tested into it and it did really well. And just about a month ago, we launched it nationwide, where for $10 a month you get $3 off every order.

It also comes with a bunch of other benefits around things like free delivery, access to a larger menu, some merch swag, some drops that we do that people love, that are very high demand, so kinda building some lifestyle components around that. And really the idea is just making it easier to live your Sweet Life. And good response so far, and I think over time, you'll see more and more customers opt for that.

Turner: So thinking through some of the numbers, $10 a month, free delivery…

Jonathan: So it’s not all week, all the time free delivery.

Turner: Yeah I think it said once per week maybe, something like that. And is it after 4:00 PM too?

Jonathan: Yeah. It's, it's evening delivery. So it allows to incentivize some of the behaviors we're trying to create, which is get people to come more at diner, get people to come more on weekends. And then the Sweetpass, the non-paid version, is totally gamified rewards and challenges. So we use personalization to offer different customers different challenges, very similar to what like the Starbucks app will do. So, hey, come three times in a week and get this, or try two things on the seasonal menu and unlock this, or just buy one, get one free. It uses personalization to give us a lot of control over which users we want to offer which things. The idea is just, how do you increase margins while still giving customers something they l they love and some benefits for being loyal guests.

Turner: It's not like you're doing anything bad. You're giving them salad, you're giving them healthy food.

Jonathan: Yeah, and then you asked about the Infinite Kitchen. So for anyone that has not been to Sweetgreen, the way it works is we source food from these great farmers -

Turner: It's locally, as much as you can right?

Jonathan: - locally, as much as we can, really focused on regenerative agriculture. Just the best produce we can find. It's really about the quality more so than where it is, but a lot of it does happen to be local, just because we love the regionality of some of those local suppliers. So we work with small, you know, small, medium, and large farms. We get deliveries to our stores every day so we do not have a commissary. We make food directly in all of our kitchens, and pretty much everything you have at Sweetgreen is made from scratch every day in the restaurant. From our dressings – that are made, for the most part, most of them are made in the restaurants – to our chicken and our proteins, they’re marinated and cooked throughout the day.

And we have a number of tools in the back of house that help guide the team in terms of exactly what to make. Restaurants have a lot of complexity and I talked about at the beginning. What most restaurants have done to limit the complexity in order to scale has been to remove the complexity from the restaurant. So totally simplify the menu, reduce the SKUs, or have everything made in some factory, somewhere where at the edge all you gotta do is put the thing together.

Our thinking was that's kind of what ruins restaurants, the quality of the food. Can we think differently about how to preserve the best thing about what we are, which is this freshly produced large number of ingredients that can be customized in so many ways - can we figure out a way to preserve that as we scale and still have great economics? And so the idea was, we're going to invest in technology that allows us to do that. There are a few things that we do that enables us.

One is in the preparation of the food - we have a couple tools that guide our teams. Think about them as GPS for the kitchen. We have one that runs cold prep, we have run that one that runs hot prep. If you are working in the kitchen, you have an app next to the oven that tells you - it has the recipe on it and everything - based off of the sales forecast and what the velocity is of what's selling, “It's time to cook chicken. Here's how you should do it. Here's exactly how much you should cook now. It's time to cook mushrooms and here's exactly I should do it.” And it measures all of this.

Similarly on the cold food - again, it's a dynamic beautiful iPad app that tells you “Don't just randomly start cooking, like chopping and washing things. Here's exactly what you should make when.” And it's fully dynamic, based off what's going on in the restaurant. So we really have lowered the cognitive load of how complex it can be to work in the kitchen and prep all of those things.

Turner: And I'm assuming with the app, you have this touchpoint with the consumer that just gives you an even more holistic picture or ability to influence all the different external factors to do that even better.

Jonathan: Correct. We have a really good idea based off of the digital connection we have, what the sales will be for the day, what the product mix will be, and what the ingredient mix will be for the day and by time period. So we're able to use that data to then just guides our teams to make the food in a much more seamless way.

You then move to what most people see in the restaurant, which is assembly. Assembly in our restaurants is them actually making the bowls down the line. Most of our restaurants have a frontline that is the one you typically see, where you come and order in-person with one of our team members working down the line. All of our restaurants also have a digital make line. This is the line I was referring to that took the place of the yogurt. Our restaurants have a separate digital make line. And this is the line where if you order online or for delivery, it's almost like a separate kitchen those orders are taken into. And some of our restaurants have multiple lines of second make lines. Some of our stores, like high volume locations in cities like New York, have two or three or even four of those lines so we can capture really high throughputs in a very short period of time.

Turner: Yeah. And I feel like you've mentioned somewhere before you guys have like 80% digital penetration in some stores.

Jonathan: Yeah, in some stores we do. Overall, it's in the sixties.

Turner: Is there a skew, like rural areas are more or in-person cities are more digital or vice versa?

Jonathan: Generally - although what was interesting with the pandemic is it really pulled forward the suburbs so you've seen the suburbs catch up in a really major way. Delivery is really big in a lot of the suburbs and we have wide, delivery radius. But yes, you're seeing urban, more pickup in urban. They have huge, huge lines and people want to use mobile order to pickup.

Turner: Do you see anything on demographics, like younger people are more likely to use digital? Income threshold - how does that change their behavior?

Jonathan: We don't see much on income. We definitely see a little bit on younger people, but on that, again, changing rapidly. Like we were really nervous, for example, about having kiosks. How are older people going to do with the technology? I think COVID just changed all of that, where everyone's just much more comfortable with screens and tablets.

Turner: My wife's grandma, she's like 82, I think, and she gets Instacart all the time now. And that was unheard of. That would never have happened.

Jonathan: You try it once and then you think why not do this?

Turner: Yeah. I mean, it's so convenient, especially if you're time constrained. It's a little bit more expensive, which I'm excited for people to figure out ways to bring the cost down to make it even more accessible. For me, a lot of things are just about time. When I'm ordering at Sweetgreen or whatever - if I can order on my phone, go pick it up, and not wait in line, I'll pay a little bit more.

Jonathan: For us, mobile pickup is the same price as ordering in-store. For delivery there’s service charges, which really we don't make go, they to the couriers, but on digital pickup, it's the same price.

Talking about the restaurant operation, this assembly part is a huge part of the business, and it's today done by our wonderful team members. But you have a few issues with this. One is you're capped in terms of how fast you can go. We've reported that our digital make lines can do about 200 orders an hour. Our front lines are slower than that. A hundred and something an hour when we're running at peak capacity. And so, one, you have your throughput constraints.

Two, you have our restaurant. Our food is highly customized, so almost 80% of bowls are customized in some way, 80% of people are doing something different. And an average bowl for us has 10 to 12 ingredients. So you think about how many individual actions have to be done perfectly to have perfect accuracy. It's really hard to do.

Just to give you some interesting math: you have 10 orders and they each have 10 things in them. You get one order wrong - a 1% error rate is not a 1% error rate. It's a 10% error rate because one out of 10 bowls has an error in it. If you ever ordered online and you've had something missing, it's just because when you're going that fast, trying to build customized items, humans naturally miss things.

Turner: Is that why we have menus? Like it's just, “Hey, there's the 10 things you need to know how to make,” and it makes it easier on both sides?

Jonathan: Oh, totally. It's a huge, I mean, we've had to design a system. One, we have great training program and we have great team members that learn our menu items, but. For the most part, most restaurants really want to make it so that “Hey, you learned five things and that's all you gotta learn.” Or “We're gonna print something on a ticket and you're just gonna follow.”

Turner: And I'm assuming probably as you shift the employees and the frontline workers away from doing the more manual, repetitive things, they’re maybe being a little bit more creative - they're interacting with customers more, maybe they're moving around the store, they're outside marketing. There's probably a lot more things they can do that's better overall.

Jonathan: So that was the thesis. The value of Sweetgreen is the fresh prep. The fact that we're buying the best food, preparing it from scratch, and we're cooking it right there. The value is not necessarily the fact that a human is putting it in the bowl for you. If anything, that's where a lot of the error rates are in us doing this. This doesn't seem like an unsolvable problem. We should be able to figure out how to automate this. And so we started thinking about it. I remember talking to people being like, “You're crazy. That's a crazy idea. Nobody wants that. I don't even know how that that would work.” at the time.

Still today a lot of people are thinking about these automated hands, so a lot of people have taken this not first principles approach. They have their restaurants, that are largely franchised, and they're like, “Hey, how can we make the franchise or the restaurant a little bit more productive by adding technology that you bolt on, on top of an existing system?” And one of the things we learned with digital ordering and how to integrate technology into our experience was you have to take a first principles approach. So if you take your existing system and just try to add online ordering, the experience is not gonna be great. You have to think holistically, day one: if you have multiple channels you have to serve, what's the best experience to design? And so we thought that same way around: automation - how would it work in a new store where you had the whole system automated from a first principles approach? And so we started working on this idea.

We actually originally started hiring our own team to do it, thinking we could build it ourselves. And then we met four college kids going to MIT - three of them were still there, one had just graduated. They were Sweetgreen fanatics. They loved Sweetgreen. They were on the water polo team. They were mechanical engineers at MIT and they were like, “We're gonna build Sweetgreen, but we're gonna build it with robots so we can make it more affordable and easier, and it's gonna be better.”

And I remember like seeing, a tiny little news clip about this automated system they built in their dorm. We went up to Boston. We met these guys, this must have been like six years ago. And we were like, “Let's stay in touch. This is super cool.” They continued on and they decided that instead of building automation for the industry, they were going to build their own restaurants, so they were going to build a Sweetgreen competitor. They ended up raising money from Maveron and Khosla - they raised like $30 million. They opened two restaurants with a beautiful automated system. It was called Spyce Kitchen. They had two restaurants open in Boston, and we stayed close and we really admired what they had done. The system they had built was amazing. But I think with being a restaurant brand, you have to figure out the technology and the operation, but you also have to figure out the brand and the food.

And I think our superpower around brand marketing and culinary, was a perfect match for their superpower, which was around engineering. And so about a year and a half ago, we acquired Spyce. In a lot of ways, it was like this perfect marriage because our mission statements were practically written the same. It was like we had the same exact idea of what we were trying to solve culturally around the food system. And so we acquired them and began working on the Sweetgreen System, which we've called the Infinite Kitchen. And just a couple weeks ago we opened our first one out in Chicago.

It's been really successful so far. We're learning a ton about it, but we do believe the future of the industry will be much more automated. As I mentioned earlier on the show: 2 million open positions, very high quit rates, very high turnover rates. And to your point earlier, we think we can make the job more fulfilling. We think we can focus the job more on the culinary aspects and the hospitality aspects versus just the repetitive aspects of the job. And so very early for us, but that first Infinite Kitchen has been very successful so far. We're excited to see what we do from here.

Turner: Any surprises just from the first couple weeks yet?

Jonathan: Yeah, I think what's been interesting. For us, we were trying to learn a few things when we did it. It was less, “Does the technology work?” because we knew the technology worked. They had two restaurants open and the day we acquired them, we put the Sweetgreen menu into one of their existing restaurants and just called it Sweetgreen pop-up and proved that the technology works.

So the questions were more - a few things. One was, do customers like it? The big fear is you're going to put this big piece of technology in a Sweetgreen, which is a very human and vibrant bustling kind of place - is it going to feel cold and sterile and not get the brand ethos across the way we want it to? Are people going to not like the ordering system? Are they going to be scared of it? Like, are they going to be turned off by it? And so that was one. So far, happy to report that people love it. I think the way you can order from a human, but you can order from kiosk or you can order from your phone - people love that.

The other thing we were trying to learn is, what are the unit economics? A store with one of these machines will be more than our existing stores, but we'd expect some labor savings and other benefits from those machines to offset the additional cost. So that we're still learning, but seems good.

I think the third is how do employees like it? Can we lower our turnover? Turnover for the industry is way north of a hundred percent. Can we get the turnover down significantly by making it an easier place to work? Early reads, our employees like it a lot more. It's a lot more enjoyable place to work.

But I think for me, the biggest learning that we weren't expecting has been a few things. One has been the actual food quality. The food quality has been improved. One of the things that we didn't realize is, you keep these foods in these perfectly temperature-controlled tubes, both hot and cold. The temperature is perfect, like you can't get it wrong. Although we're pretty good in our normal stores, it's perfectly controlled. And because it’s covered, the food doesn't get oxidized. Even the color in the food coming out of the kitchen is brighter.

Turner: Can it change how you operate your supply chain and how you procure stuff a little bit if they're in these controlled environments?

Jonathan: We're starting to think about it like does it change how we procure? But I think the other thing has been around portioning. You know, no matter what, getting portioning by hand correct is really hard. I mean, think about dressings. At Sweetgreen, we ask you light, medium, or heavy? We can train people how to do light, medium, or heavy… or you can have a machine that measures perfectly exactly what the different portions should be. For me, I spent the first few days there and I was just amazed. I wanted to eat the food more and I felt like the food quality was better and just the experience was better.

And then the last thing, which we knew was something, but it was very hard to quantify, is: what are the benefits of no longer having a line? When you order at the Infinite Kitchen, your food comes out in approximately three minutes. You were saying earlier like, “Hey, I have to make a decision around food and I have to order on my phone before or I have to go and potentially wait.” What happens to the consumer behavior when that is gone? Where you can walk into a restaurant and whether you've ordered an advance or not, have your food in three minutes? These machines have higher throughput than our existing lines – what happens when you can capture all of that demand that you were maybe missing? So again, learning a lot, but very excited for what this can do for Sweetgreen.

Eventually what our goal would be is leveraging technology to make healthy food much more accessible. There's a huge system that we're kind of fighting against here and today we're in the phase of “make healthy food desirable.” The first job is just like, make people want it. Because you can't go tackle food deserts and food access issues if people don't want to eat this food and it's not craveable and cool, and something that people just really desire. Once you've captured that, I think using technology and innovation to lower the cost curve, you figure out how to then make it accessible to more places. That's the holy grail. Take this and then eventually be able to kind of be ubiquitous by eventually being able to have food that can serve people in any community and still do so profitably.

Turner: Yeah, and you kind of think about just the food system. You open up your fridge and take out whatever you're eating or your pantry, or you go to a fast food restaurant and the burger's already prepared, and you're just ordering it and they hand it to you - it's good, some pieces of that. Some parts are not very good. Are there any interesting stories or stats you've heard on ways that food impacts you that we might not even realize or think about down the road?

Jonathan: I think about it a lot. I think the key to health is food, sleep, and exercise, the three major pillars. We as a society should figure out how to build a system that actually promotes these more versus the opposite, which is a lot of lobbying and special interests driving the cost of foods that are really bad for you. Also, a lot of regulation. For me, processed food and cigarettes are not that different. And the fact that we can't market cigarettes to children, but we can market all this processed food to children - I think it's crazy. There was recently a bill introduced in Congress that was around, SNAP benefits and what they can go towards. It's kind of crazy that $240 billion dollars of SNAP benefits, government-funded money, a year goes towards ultra-processed food. Food that has zero nutritional value, absolutely zero. I think SNAP benefits are really important, but we should make the SNAP benefits useful for things that are actually nutritious and nourishing, not things that not only have no nutritional value, but are going to kill you. And then on the other side, we're going to pay for the healthcare for these people that we're making sick. Of the $240 billion, $60 billion a year goes towards soda.

Turner: That's higher than I thought it was. I thought it was like 10%.

Jonathan: Yeah, taxpayer money - give $60 billion to Coca-Cola. On the $240 billion, you could say, “Hey, there's no other option. People need to eat or they're hungry.” Okay, fine. But there's no excuse for the Coca-Cola. It just doesn't make sense to me. You can drink water. There are other ways to do it.

Another stat that's always been interesting to me, related. About 50 years ago, if you look at, per capita spend on food versus healthcare, it's really interesting to see how those lines have crossed. It used to be we spent twice as much on food as we did on healthcare. Today, it's exactly inverse, so we spend twice as much on healthcare as we do on food. I think it's just very related. It's hard to solve these problems further upstream because you're making investments for decades. Maybe there's not as much money to be made around the pharma that then goes and solves these things. Like Ozempic, etc., is going to be the most profitable drug of all time. Unfortunately, eating healthy is not as profitable as some of these other drugs may be.

I do believe incentives in a system are really important. And it's not that people are bad, and I do not believe consumers want to make the wrong choice. The obesity problem we have in this country where 40% of people are obese - it's not because consumers have a lack of willpower. It is a system that is driving that. It is a society that is making that food cheap, marketing that food as all there is to eat. It's a culture that is infiltrated by that. Our goal at Sweetgreen has been - how do you make it, like I said, desirable. You want to build a Nike. Like I look at a company like Nike or Disney, just meeting the customer where they are. For us: I want to eat this just because it's the best-tasting thing and the brand that I love most with the best experience. Oh, and it happens to be healthy. And that’s the only way we can kind of change culture, not by telling people to eat their vegetables.

Turner: Yeah, and I think it’s kind of like, capitalism's great but there's downside. There's a lot of upside but whatever is the most profitable, people will do it. When you think about the new consumer, kind of how we've been changing, people are sometimes willing to pay a premium for something that's health-related or better for them. So maybe it is more profitable.

Jonathan: Take a broader view on the total system and the health of people overall - how would a system be designed, not for sick care, but for healthcare?

Turner: That's a good way to think about it. You had a really interesting word that you’ve used before: Conscious Capital. It's kind of the intersection of a lot of this stuff. Can you just explain what that is?

Jonathan: It's the core value at Sweetgreen that we have called Win-Win-Win, which is about making decisions that benefit our customers, our team members, and our community. And really it's that triple bottom line. I think if done right, they're not at odds with each other.

Doing the right thing sometimes costs more, but done creatively and with the right time horizon, can create a really durable business. Case in point, Patagonia - great business, does a lot of the right things, just been named the most beloved brand. They have a very strong position in a lot of things they do, but that reinforces their brand and makes them more successful. I think it's very hard to do. In order to do it, aligning your stakeholders is important and playing an infinite game around time horizon, because doing the right thing may not help us in the quarter, but will help us if we're playing for decades and generations. And so I think you can only do it if you increase your time horizon and the game you're playing for. Because otherwise you can always take that short term cut. That's the idea for me, is finding those creative solutions where we can balance the interest of all of our stakeholders.

Turner: Yeah. And there's probably some something to be said about getting a bigger base of restaurants or fixed costs, leveraging the base you have, lowering prices, increasing access, more revenue, which of course lets you open up more restaurants, continue to leverage the fixed costs…

Jonathan: That's exactly the flywheel. And that's why, people say restaurants are bad businesses. And mom-and-pop one one-off restaurants can be very hard businesses. But it's also a very durable business and at scale can be really fantastic. So you look at a company like Chipotle, it’s almost a $60 billion market cap company. I think people are surprised by that. They have over 3000 restaurants in the United States. And if you look at companies like Chipotle or Domino’s, they've been some of the best investments over the past 20 years.

They can be fantastic investments at scale because the barriers to entry on single restaurants are very low but the barriers to entry to creating a large restaurant chain are high. Similar to retailers, anyone can go open one retail shop, but to create a platform like a Walmart or Amazon? Huge barriers to entries. And I think that, that, over time there is a huge moat around these sorts of companies because of the flywheel that you described.

Turner: I did have one final question that I was kind of intrigued by reading an article from a long time ago. You said that you and all your co-founders used to play a lot of board games. Do you have a favorite right now or historical? I think you mentioned Settlers of Catan was one. This is like 10 years ago.

Jonathan: Still Settlers. I still think it's one of the best games. So fun, like human dynamics. It's everything about it. First time I did the expansion pack was fun.

Turner: Seafarers or Cities and Knights? Which one?

Jonathan: Cities and Knights.

Turner: Oh, nice.

Jonathan: You Settle?

Turner: I do play, yeah. Not as much as I'd like to. We try a lot of new games too. Honestly, we play a lot of Sequence. Have you ever played Sequence?

Jonathan: No, no. Is it good?

Turner: It's pretty simple, but my six year old can play it and she's so good. I don't know why. Her win rate is like, I don't know, 70%, which doesn't make any sense for a game that you think is random and she's like six years old.

Jonathan: That’s amazing.

Turner: Awesome. This was great. Anything you want to end with?

Jonathan: Yeah, I think, for me, advice less for starting a restaurant, but for an entrepreneur would be: I think our society really glamorizes overnight success. You can look at Sweetgreen and be like, “Overnight success!”. People don't know we've been at it for 17 years.

I tell people all the time - every day, multiple times a day, I feel like I'm on the verge of world domination and bankruptcy, constantly. And I'm paranoid. I'm like, “Is this all gonna end? Even today we're a public company with over 200 restaurants? Are we doing anything right? Are we gonna make it?”. Or like, “Oh my God. This is going to work and we are going to be the next McDonald's!”. And I think that being an entrepreneur is as much an intellectual challenge of coming up with the right idea in the business, but it's also an emotional challenge around the ups and downs, the heartbreak, the relationships. And I think so much of the success is just not giving up.

With Sweetgreen, I don't think we're like that much smarter than anyone else. I think that we just kept going and we'll outwork people and keep going and learning and being very reflective around learning - quickly iterating from the mistakes we've made. But just that relentlessness, I think is so important for an entrepreneur. And so what I tell people is I think it's not for everyone, and if you're gonna do it, be willing to commit 10 years. 10 years of some failure to get there.

And on that note, everyone's talking right now about Nvidia, right? And it's just like, yeah, Nvidia and AI! This guy started 30 years ago. A 30-year overnight success. It was 30 years he's been grinding at this thing and seeing something that he believed in very early on and continuing to evolve and position it for that next wave. I don't want to say there's no such thing as overnight success, but wishing for that is kind of like winning the lottery. So just always, always, believe in taking the long view.

Turner: Yeah, I mean, talk about planning for the future. I think it was 2012 or something. He was like, “We gotta get ready for AI. And people were like AI? What is that?”

Jonathan: It's just amazing.

Turner: Well, this was awesome. Thank you so much for coming on.

Jonathan: Yeah. This is super fun. Thanks for reaching out on Twitter. I've been trying to do a little. You do a great job on Twitter. I've been trying to play with it a little more. I never did much tweeting, but I think I might start.

Turner: Yeah, you should. What’s your username on Twitter? We'll have people follow you.

Jonathan: @jonnynemo

Turner: @jonnynemo. Awesome. Good to chat and make sure you follow Jonathan on Twitter.

Listen to the episode on Spotify, Apple, and YouTube.

Find transcripts of all other episodes here.