🎧🍌 Lessons From Building Mercury with Immad Akhund (Co-founder and CEO, Mercury)

Lessons from selling a company for $45 million, how to get free legal advice, cultural mistakes most startups make, how to fundraise, and the embarrassing pitch that raised a Seed from a16z

👉 Stream on Apple, Spotify, and YouTube

Immad Akhund is the Co-founder and CEO of Mercury, a digitally native bank for startups. Mercury is supported by investors like a16z, Coatue, CRV, Chapter One, Ryan Peterson, Scott Belsky, Serena Williams, Terrence Rohan, Zach Coelius, Todd Goldberg, and more. Before Mercury, Immad was a part-time partner at YC, co-founded Heyzap which sold for $45 million, and co-founded and scaled Clickpass to millions of users.

Find Immad on Twitter and LinkedIn. Check out his new project, The Curiosity Project, where he interviews the founders of companies like Replit, Jasper, and Substack about AI, nuclear energy, and the future of media.

This episode is brought to you by Secureframe, the automated compliance platform built by compliance experts. Book a demo here.

To inquire on sponsorship opportunities on future episodes, click here.

In this episode, we discuss:

The future of banking

Why Mercury’s beautiful onboarding was an accident

Cultural mistakes most startups make

Two lessons from selling his first company for $45 million

How to get free legal advice

Why it’s better to build a network of entrepreneurs than investors

How to fundraise

Why its contrarian to start a non-AI company right now

How Mercury is thinking about AI

Why each operational team has its own engineering team

The embarrassing pitch meeting that raised his Series A from a16z

How crypto used up all its goodwill

The hiring advice he gives every founder

Follow The Peel on Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok.

Thanks to Zac and Xavier at Supermix for the help with production and distribution!

Transcript

Find transcripts of all prior episodes here.

Turner Novak: Immad, thanks for joining.

Immad Akhund: Yeah! Thanks for having me Turner.

Turner Novak: So first question, I'm a Mercury customer – big fan. I think of it as my bank, but it's not technically a bank. Can you kind of explain what that means and how the product works?

Immad Akhund: Yeah. From a regulatory and licensing perspective, we are just software providers to our partner banks. For most of the banks you use, whether it's SVB or whatever, the actual mobile app and the website are made by other software providers. Banks don't, generally speaking, have engineering teams that build this stuff.

From a licensing perspective, it's fairly similar. We don't touch our customers’ money, like there's no point where we take custody over your funds. If you raise from LPs, they send money from their bank, and it goes straight to Choice Financial or Evolve Bank & Trust, which are our two partner banks.

And then when you make an investment, you basically instruct us to say, “Hey, I want to send this much money to this other bank account.” And we then work with the bank’s backend systems to send it.

I had this idea in 2013 and I started in 2017. It wasn't obvious whether you could deliver a great experience by just being software that sat in front of banks. A few people had done it, but I thought by this point – wherever we are in 2023, it's been six years – I thought we would need to get our own bank charter to really deliver a great experience.

But it turned out we can deliver a pretty good experience, working with these kinds of sponsor banks. And that whole ecosystem has really evolved in the last six years to enable that.

Turner Novak: Would you ever get a bank charter?

Immad Akhund: Every year we look into it – at some point it's more of an ROI calculation. It's actually not that expensive.

One of the reasons we don't do it – and I think you as an early-stage investor will appreciate this – if you were to think, what are the two characteristics of an early-stage startup or high growth startup? Number one, it's unprofitable. And number two, it grows fast, right? Those two characteristics are basically antithetical to what bank regulators would want of a bank.

A bank that's unprofitable and growing really fast is very scary. And actually, if you look at SVB’s failure, we could talk about why did they do this, etc., but a lot of it stems from the fact that they grew really fast.

Don't quote me on this but I think they grew from like $90 billion in deposits to $200 billion deposits in two years because 2021 was crazy. And when that happens, it creates this pressure and the CFO at the bank is like, “Hey, we grew deposits. What should we do with all this money?”

Obviously, they decided to put in 10-year bonds, which turned out to be a bad decision. But it is that high growth pressure that creates bad decisions at times.

Having said all of that, we have been profitable for the last four quarters, so at least that part of it, we've ticked. We still want to grow fast, so it's something we do explore.

I really think about it from a customer perspective, like, “Okay if Turner is using Mercury, would he have a better experience if Mercury had its own bank charter?” At least right now, I don't think that's the case.

Turner Novak: Yeah, it's a really good product. I can tell it's all you guys think about, the user. That's why I signed up, because I looked at a bunch of banks and I think Todd Goldberg, who I think is an investor, was like, “Hey, check out Mercury.” And I was like, “Oh man, this is great.” I got an account in less than a day or whatever the time was and logged in and it was super easy to use.

Immad Akhund: You know, one thing that's interesting which is maybe a good lesson for other people is, it was almost accidental that Mercury's onboarding experience was quite so good.

What happened is, we started this in like 2017 – August 2017 is when we incorporated. We were basically ready to launch in November 2018. But our partner bank at that time – I guess I can say who it was, it was BBVA – they had made these promises to us.

They were like, “Oh, we're going to have wire support. We're going to have immigrant founder support.” They'd make these promises and every month we were like, “Okay are we getting them?” And then a year later they had not delivered on them, so we ended up switching partner bank at the last hour.

So the designer and the front-end engineering team, which was basically me and another engineer – we had a bunch of time on our hands because we were like, “The backend engineering team has to do this whole integration from scratch.”

So we re-did all of the onboarding. We did all the bits that when you do the initial MVP, you're usually like, “Oh, let's skip that bit.” At that time, I was like, “It's a one-off experience, why make it that good?” But we ended up making really good and it creates this initial impression that really lasts.

I think if you talk to a lot of customers, everyone's always like, “The onboarding was just so seamless and great,” even though you've been using it for years. You could talk about some of the other stuff, but it creates this first impression that's lasting.

It has made me re-evaluate how important the onboarding experience is, and now I'm like, it's actually really important. We are about to make the split, so we're going to have two engineering teams that are focused on the onboarding experience.

Turner Novak: I was looking probably two or three months ago – another bank I was looking at, my email chain with them was 76 emails over the course of a couple months. And I don't think I ever even got an account made. That's the other side of the experience, so I've definitely always really appreciated it.

Why is it bad for a fintech company or for a bank to grow fast? What are some of the downsides of that, like why don't regulators like that?

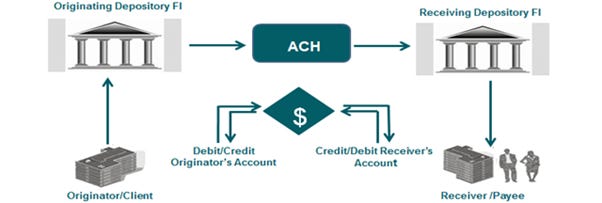

Immad Akhund: The reason banking is regulated in the first place more than a software company would be, is that it's based on this fractional reserve model. For normal banks – and this isn't true for Mercury customers, which I can also talk about – like SVB or whatever, if you put $10 million in, they will take $8 million and they will lend it out.

Turner Novak: And that's because they need to make money in order to pay you your interest.

How banks make money through the fractional reserve banking system. Source: Bankroll Zen

Immad Akhund: Yeah, to some extent it's also because they want to make money. And that provides a valuable service, right? Like the $8 million goes to other businesses and consumers. It helps the economy. Lending exists for a reason, it does something similar to what VCs do, right? You invest now for a future return. You are helping build something and that's what kind of what lending does.

Most people couldn’t afford a house, but if you give a mortgage it lets them get the house today, get the value of the house, and they pay it off and the bank makes money and they get they get an output. That's kind of the banking model that's existed for a thousand years or something, right?

Turner Novak: But it's changed a lot – or at, at least the software around it has changed quite a bit.

Immad Akhund: And yeah, you could say the fundamentals of the internet changed it a lot as well. But anyway, so coming back to the original question, if that's the model, it's obvious how depositors would get screwed often if you did not regulate it because the bank's incentive is to go take risky loans or just not be that sophisticated about it. And they would eventually screw it up.

This used to happen all the time, like even in the seventies there were way more bank failures. And 200 years ago, this was just the normal, like 10% of banks failed. The regulations over time were like, okay, we need to protect consumers. And that's why regulations exist and that's why banks have to be regulated.

It’s like any sort of regulation, like the FAA or whatever would like look at a plane crash and go, “Okay, the plane crashed. What were the reasons that that plane crashed?” And that's happened over a hundred years with banks.

If you look at banks and they fail, like what are the reasons they fail? One of the reasons is they grow fast and they do bad things, like they take riskier loans. Failure is just more likely to occur in this situation where you grow fast. If you grow slow or you've been doing the same thing for 30 years – there’s is a term for it –if you've done the same thing for a long time, you're more likely to continue to do it successfully.

Anyway, if you 2x your deposits, then you will end up doing 2x the loans normally. Most systems have a hard time absorbing 2x loans. The way Mercury works, which is relevant and interesting – Mercury is a software company and can't lend in those deposits.

The two banks we work with are much smaller than the amount of deposits we send to them. Evolve is about $2 billion and I think Choice is around $3 billion, and we have tens of billions of deposits. So those banks can't actually host those deposits on their balance sheet.

The way they function is they have these sweep networks. They work with a bunch of much bigger banks that are in the sweep networks. I was told by at least one of these banks – not to name them, but you can actually look them up online, which banks are in the sweep networks – there are trillions of deposits in the sweep network banks.

The money is not held by us, even by our partner banks. It's not held by them. It gets swept into a bunch of these banks and those banks as a whole can lend against the money. That’s partly why they want it, but because it's distributed, you end up getting more FDIC insurance.

We guarantee that if you have $5 million deposits, it'll get swept to at least 20 banks that give you $5 million in FDIC insurance, so that's a very different model to a normal bank model.

Turner Novak: Yeah, you're almost like lead gen or deposit acquisition, sort of a sexy software layer.

Immad Akhund: Yeah. There's definitely a piece of that. And there are payment volumes. Banks actually are like a weird combination of like three things. At its core, it's a deposit function, a lending function, and a payment function. And there's no actual strict reason why the same company needs to do all three of them.

It made sense when like you had to walk into a local branch and there was only one bank in your town, but in the modern internet parlance, you would expect that to get like unbundled, and to some extent we do that.

Turner Novak: Yeah, and I think we're going to stop talking about the banking system. If anyone is interested in walking through all this, he did a podcast with Logan Bartlett. If you just search Logan Bartlett, you can find it. We'll throw it in the show notes, it's like two-hour podcasts. He spends the majority of it really digging into all this stuff, so definitely recommend checking it out if you want to hear 10x more going way deeper on this stuff.

How do you think the industry is going to change over the next 10 years? Because that's definitely relevant to Mercury and what you're doing. What are you expecting as you think about positioning Mercury? What can we expect on the product side? Anything you can share?

Immad Akhund: Yeah, the thesis for Mercury was and is that banks are delivered via the internet now. Bank branches I don't think really need to exist. I don't think anyone enjoys going to them. I certainly do not.

Imagine more advanced ATMs, I think that's interesting. You might want to talk to someone or like deal with cash via an ATM in a more advanced way. We deal with tech-enabled businesses on the whole and I've been doing startups since 2006, like I'm never really needing to go to a bank branch unless I'm forced to do it because the bank can't do something online. So that's kind of the thesis

I think it's also relatively recent, right? Like, I would say it's only since maybe the last 10 years that people have moved almost completely to bits when it comes to money. I think in that world it's hard to believe that these kinds of a hundred-year-old banks will be the dominant player when it comes to delivering financial services.

I think it will be a combination of people like Apple and people like Mercury. And there will still be – if we still have lending and niche kinds of lending – we’ll still have more traditional financial institutions running it.

But I think for the broad set of things that people expect out of banking – credit cards, bank accounts, even the basic loan stuff like mortgages, car loans, etc. – I just think it's going to be delivered by tech companies on the whole and that's a really fundamental shift.

I don't want to speak too badly of normal banks, but if you look at the top 10 companies in the US, none of them are banks. But if you look at the next hundred, 20 of them are banks or something. So banks are worth $2 trillion or something in the US.

A lot of money is in banking but banks make it sound like they're these poor institutions – that they hardly make money and it's so hard, the multiples are low. I think they've created this aura of “We are not actually successful” so that they don't get regulated or something. There’s a lot of money in it as a percentage of GDP, like banking and defense – these things are big chunks of GDP.

I think there's going to be a big shift in that towards like when we say tech companies, it’s customer-first product and company, right? We really care about the experience that Turner has. I don't think most banks really care about the experience that customers have. They're very old.

Institutions have had a regulatory monopoly for a long time, so it's a very different mindset. I think overall it's going to be better for customers. It's probably going to actually reduce the amount of revenue in banking, which is an interesting point.

Essentially, financial institutions are like middlemen – they extract money out of the system. And if you bring competition, if you bring the internet and the ability to select a large set of products, I think it'll be more convenient for people. It'll also probably have less fees associated with it and deliver the same or better product for less cost to consumers.

I also think the whole system will be more efficient behind the scenes as well. Mercury doesn't have to pay for expensive buildings on every street corner. That cost saving we have, we can pass on to consumers. The whole system is just better. Maybe even the net profit in the system will be the same, which is kind of the magic of technology.

Turner Novak: Yeah, and isn't a lot of the banking system still run on IBM mainframes and spreadsheets?

Immad Akhund: Yeah, it's really old school.

Turner Novak: I think you've kind of talked about publicly, you didn't know anything about banking at all when you got into this. What's the story starting Mercury and coming up with the idea? You’re obviously not from the US where you live now. Can you walk through this story, the journey of Mercury, all the insights that you learned?

Immad Akhund: So I'm from the UK originally. That's where I grew up. I did my first company there and I moved to the US in 2007. That was the start of the kindling for this idea. Banks are better in the UK historically…

Turner Novak: Like less monopolies?

Immad Akhund: It's weird, actually more monopolies, but the regulators – this is my external impression, I'm not deep in the UK system – in the UK system, the regulators are like, “Hey, you now have to adopt this payment rail that makes money move instantly.” And all the banks adopt it or they're like, “You can no longer charge ATM fees” and then the banks can't charge ATM fees

It's much more specific and they get into the nitty gritty of it, whereas in the US my impression is that regulators mostly leave alone how banks do things but obviously like get involved on the loan side.

Turner Novak: Yeah, we kind of let crypto happen for years here.

Immad Akhund: I mean there's some magic to it as well, right? There are thousands of banks in the US and there are only 20 or something in the UK. But either way I was like, this is kind of weird that it's bad here. I thought Silicon Valley is supposed to be the future. So that was my first impression.

Turner Novak: Did you move for YC?

Immad Akhund: I did a YC company in ’07 and another one in ’09.

Turner Novak: What was the first one that you did?

Immad Akhund: It was called Clickpass. It was an easy single sign-on system for websites before that stuff was like, cool.

Turner Novak: Okay, so this was like login with Gmail or Facebook?

Immad Akhund: Exactly. It was a developer tool that would help people set that up.

Turner Novak: Interesting. Anything interesting happen there? Like any learnings or did you guys get any customers? How did that go?

Immad Akhund: Yeah, I mean, there are always learnings from all this stuff. We had a bunch of customers. Actually Hacker News[1] was using it. Washington Post was using it. This company called Disqus – do you remember? It was a comments system.

Anyway, there were a few YC companies and some non-YC companies using it. It actually had a lot of users, a few million maybe. But we just didn't have a way of making money, we hadn't thought that through very much.

[1] Hacker News is a Reddit-like social news website run by Y Combinator focusing on technology and entrepreneurship.

Turner Novak: (laughing) It’s the last thing you think about, how do we make money…

Immad Akhund: Yeah, we were really focused on “Let's get a Series A,” but, at least back then and maybe now too, just having users and not making money was not a good way of getting a Series A as we also didn't have a very credible story on how we would make money.

Turner Novak: What was the story? What did you tell people?

Immad Akhund: Not good. We went through a ton of different stories. This was a little more common in 2008, but we spent months and months fundraising. We would go, “The story is now X. We're going to go charge blah, blah, blah. We're going to go charge consumers.”

We went through a bunch of stories and none of them worked. I think one of the interesting lessons was: if you are not convinced by the story, you're never going to convince investors.

I think sometimes founders kind of pretend to themselves that they find their own stories convincing, but I think in our heart of hearts, we did not find our own stories convincing. And I think investors can pick that up pretty quickly.

I think sometimes founders kind of pretend to themselves that they find their own stories convincing, but I think in our heart of hearts, we did not find our own stories convincing. And I think investors can pick that up pretty quickly.

We ended up doing a talent acquisition for that company. It was just getting a high paying job, which is not what I wanted. So I did another startup after that.

Turner Novak: Yeah. Right after, it sounds like.

Immad Akhund: Yeah, there was no pause at all.

Turner Novak: Okay. And that one was Heyzap?

Immad Akhund: Yeah. That was Heyzap, which we did from the end of 2008 to when we sold in 2016. And don't ask me about lessons from that because that was eight years of lessons. (laughing) It would be the whole podcast.

Turner Novak: Ok so what do you think is the most valuable and applicable today?

Immad Akhund: I mean, there's a ton. One thing that I we did a lot better at Mercury, which I had to and I never really understood until I finally figured it out later at Heyzap, was how important culture is and also what is culture like? People were like, culture, culture, culture.

And I was like, your first impression for culture is: are there beers in the fridge? Right? Is that your first impression of culture? That's my first impression.

It’s like when people say startup culture, right? Beers in the fridge, maybe massages, ping pong table. And I think that is a symptom of culture, but it's definitely not culture.

And I do think culture is a weird word, like it means lots of different things. I think the bit that is quite important and important to get right very early in a company is, what are the personalities that you have at the company?

And which ones do you hire for and what personality traits do you encourage? And some of these work fine, but are completely contradictory. It’s like that Ben Horowitz book says, “What You Do is Who You Are.” That book is pretty good about explaining what I think culture is.

But if you take Uber's culture, whether it's hyper-competitive or high-ego, you work your ass off and you win no matter what. That worked for them. I know people think Uber is not successful, but it's a $40 billion company or something, like it was extremely successful.

Turner Novak: I think it's a hundred now. I don't know if you've seen recently, but they were free cash flow positive in the most recent quarter.

Immad Akhund: Yeah and it was built on that culture. They crushed all the competition getting there, whereas I'm not like that at all. That’s not the culture of Mercury. We are all about like hiring humble people that want to be helpful, that are low ego.

We are all about like, ignore the competition and just go focus on customers. Both cultures work but you have to be like true to one or the other culture. And if half your company is humble, low ego people and the other half is competitive, high ego people, then it's probably just going to break and you need to build systems around it.

Turner Novak: Yeah. That's fair. Maybe it depends on industry too.

Immad Akhund: Yes, exactly. Your culture has to work within the company, but ideally it's expressed in the product and the customer experience that you deliver. I think banks are actually, generally speaking, a little higher ego, a little less customer centric, and we don't want that. We want the opposite of that.

But it also has to be true to the founders. I think culture is bottoms-up innovation and giving people a lot of authority and trust and control. But culture for whatever reason is a very top-down thing.

If you behave in a certain way, it's hard for some other way to get manifested, so it has to be true to who you are. I guess I was 23 when I started my previous company, I probably just didn't know who I was either. It’s hard to create a good culture when you don't understand yourself, which is kind of a tricky aspect of that.

That was the biggest lesson. We wrote, even when there were just four people at Mercury, we wrote down what we cared about in our culture. And we ever since then, we've hired alongside it and come up with ways of testing for it and encouraging it in the company.

I think that's been a really powerful part of it because, yeah, people often talk about mission and things like that, which I do think are important. But at the end of the day, who you work with and what you do at a company is pretty much the same in most companies, right? In front of a computer, you're a programmer, you're coding, or you're designing.

Those things are fundamentally fairly similar between companies, but the people you work with and the culture that exists actually are probably more of a defining characteristic of whether you enjoy it more than the mission. The mission matters of course, but it's probably not going to change what you do day to day and whether you enjoy it. You could be on a great mission, but hate it because the people.

Turner Novak: I could see them tying in together where, if both of them really click, then that's probably the magical work environment.

Immad Akhund: Yeah. That was the biggest lesson. The second lesson, which I don't know how fulfilling it is to people but it is to me to some extent is, I don't think I was that much worse of an entrepreneur in my previous company. Mercury just worked way better.

Having the right idea at the right time – timing is really important. It's so important that people should probably spend a lot more time on the idea. I had this thought process that you shouldn't care about the idea so much that execution was everything. And that a good entrepreneur would figure out, executing any idea or being able to twist and turn through the idea maze while you do it.

I think it's not true, really. I think execution matters, but I don't think you can take a bad idea and execute the hell out of it. But I think you can take a good idea and execute it well. I think even if you're slightly bad at executing a good idea, you can probably like learn. But there's no way to like learn your way into a bad idea. On the whole, there are probably exceptions.

Turner Novak: Yeah. And it's probably that, famous Mark Andreessen blog post where there’s the grid with the four squares and it's like, 1) good team, 2) bad team, 3) bad market, 4) good market. And you try to find intersection of really good founders, really good market.

You could be amazing. You could be the Jeff Bezos, the Elon Musk of the world – but if you're trying to sell software to K-12 schools or something, or one of those markets that everyone knows is just a slog, I don't care who you are, that's tough.

So, okay, you've learned all these things from Heyzap. You're thinking about what to do next. I think you've mentioned, you ran into this problem that Mercury solved. What was the moment where you decided this is what I'm doing?

Immad Akhund: You know, Heyzap was often struggling during the eight years. So, because it was struggling and I was very interested (I live in San Francisco) in startups, there would always be these ideas that were in the back of my head.

And as an entrepreneur you always have ideas about how do I make my life easier? Those are the easiest ideas to come up with. And I'm not saying that I came up with these ideas, but you could see things that sucked as an entrepreneur.

Payroll really sucked for a long time. I remember we were signing up to ADP and it was me and my co-founder, we are literally living and working in an apartment in Soma and this guy comes in. He's got a literal binder and he is getting us signed up to payroll.

And I was like, this is insane. It should just be online. How does the cost work out that this guy has to physically come here to sign up guys? It’s insane.

Turner Novak: Did he have a suit and a briefcase?

Immad Akhund: Yeah, it was full-on 1990s kind of stuff.

I was like, this is just clearly dumb, someone needs to improve payroll. And then Gusto came along and did that. There was no Stripe, there was no Slack, almost everything to do with being an entrepreneur sucked. It was all of these old school enterprise-y companies that were impossible to use or sign up for.

Banking was one of these things, so as these things improved, I was like, “Oh, tick, that's done. Someone should do X.” And then someone else did X. And I was like, “Okay…”.

There aren’t that many services that every single business uses, right? It’s like payroll, website hosting so AWS, banking – there's basically like 10 or so things that every startup needs. It was just one of these things where I was like, “Okay, it's just going to improve at some point.” So I had this idea develop over years where I was like, someone's going to do it. And then I think it was around 2013 where I was like, “If I had time, I would just do it.”

But obviously I was still working on that startup but what I started doing, which if you have the luxury of ears, you could start doing, is I started collecting contacts. Every time I met someone who was in fintech, I would write their name down or at least mentally go, “This is someone I could turn to if I ever did this.” Same with VCs.

There was a reasonable amount of fintech innovation. So there were people that you could build on the backs of. And then in 2017 when I did Heyzap, I was like, this is still my favorite idea. I was pretty sure I could build a product and I was fairly sure I could get the customers. The bit that I was not sure about at all was like, how the hell do I do it? And is it just completely impossible?

Turner Novak: Yeah. Because you were starting a bank and in your mind, it’s very hard to do. I don't know if everyone's seen that chart where it shows number of bank charters issued over time and it just stops – it goes to zero in 2007 and no new banks have been created or very few. How did you figure things out? Like what was the process of learning about all this stuff?

Number of new FDIC-insured commercial bank charters in the United States from 2000 to 2022. Source: Statista

Immad Akhund: I think that's the power of Silicon Valley. The two most useful people, there were the two founders of this company called Standard Treasury that sold to SVB, Zach Townsend and Dan Kimerling. At that time they were starting a VC fund that was investing in fintech.

They were just great. They spent like hours with me going, “What about this?” And it's not like they knew exactly how to do it, but they were just further ahead and you could just spend a few hours and absorb all their knowledge.

The other thing that was really useful, which is probably unexpected, was talking to lawyers. One trick I have if you want to learn something about law and not pay for it is: if you talk to one lawyer, you ask them a bunch of questions, you'll have some follow-up questions. So you go to the next lawyer and you ask them the follow-up questions.

There are a surprising amount of things in legal that are gray areas. Before I started my career, I was like, “The law is the law.” It’s X or Y – but actually a lot of it is, “You could maybe do this, but maybe not.” And no one's really tried it, especially when it comes to things that are truly new.

I basically got to as many lawyers as possible. There's a fintech lawyer at every single big law firm, and then there are a bunch of specialist fintech lawyers. I probably spoke to 12 or so lawyers, some of them multiple times.

They were very generous. A couple of them ended up investing in Mercury and we also hired a couple of them eventually so I wasn't just abusing their time. But yeah, they were very friendly and, and helpful.

Eventually you just keep asking these questions and you're getting the same answers back. Or every other lawyer is giving me contradictory answers, which means I'm at the edge of the knowledge kind of gap. So that was very powerful.

Fintech VCs were quite useful. I talked to a bunch of those guys and girls. And it’s like anything right? And then I started it.

I remember after the first few meetings, I was like, “Wow, I have no idea what the fuck these people are talking about.” Because someone would say (and now it seems basic) Nacha[2] and I'd be like, “What is Nacha?” And I don't want to sound like an idiot and keep interrupting them, but eventually I would write down every time they said something and I would Google it.

[2] Nacha stands for the National Automated Clearing House Association. It operates one of the major networks that carries electronic financial transactions between banks and payments services providers. It is responsible for the rules and standards that are used to move money between accounts held at various types of financial or payments companies. It is a secure, cost-effective and efficient alternative to the processing of paper checks or wire transfers. Source: Payments Innovation Alliance

Eventually I got to the point where I was like, I kind of understand what the hell's going on. And that was an important point. One lesson there is that it’s worth knowing what you don't know and I think a lot of this pre-seed side of things should be all about de-risking what you don't know.

One's initial instinct here might be to start coding but I knew I could build a product. We'd built like 15 years of products – most investors could believe I could build a product, right? So there's no reason to de-risk that. Me spending that initial six months writing code would not have helped anyone believe anything.

So you really have to spend time de-risking the thing that is the biggest risk, which for a long time was how do you even do this? Is this allowed? What is the compliance and regulatory framework? And eventually I came to this conclusion that the way you do it is partner with banks.

And then I did a separate, very long process of locking down a bank partner, which as we mentioned earlier, turned out to be the wrong bank partner.

Turner Novak: What was the context around that? At the end did they just say, “Yeah, we can't do the wires?” Did they kind of rug pull you guys, or what happened?

Immad Akhund: No, this is a long story, but basically this company had bought Simple, the “bank”. They were not a bank as well – they were a software company that was called Simple, that provided banking services. And those people had been tasked to go build, open banking or a banking-as-a-service platform.

They were good people and they really wanted to be helpful. And they were tech people. They were like, “Yeah, we are disrupting banking by opening up APIs to banks.” So they were great and they really wanted to deliver it, but they were attached to a pretty old school, fairly big bank. BBVA is the second or third biggest Spanish bank or something like that, that owned this US subsidiary.

It was just hard for them to get it done. It wasn't their fault. They wanted to do it. The APIs were actually pretty good. They knew how to build tech, but the compliance folks at the bank just locked them.

Turner Novak: Yeah, it was from the top. Once you get past a certain step, they're just like, “No, you can't go any further.”

Immad Akhund: Yeah. And the way compliance works at a bank – even at Mercury which is not a bank – you can't go to compliance to say “We're going to do this.” Compliance has to want to do it and it's an interesting kind of thing. There are literally people that are personally liable if they make bad decisions in the compliance team.

It's not like they have a very serious kind of role and the regulators hold them up to that. It's tricky. You can have an exec team, especially at a bigger bank that's an older school institution, that's like, “Yes, we want to go support Mercury and we want to do all this cool stuff.” And then you can have a compliance team that's just like, “No, sorry. This is a bad idea.”

Turner Novak: So what was going on with this other compliance team that did that did say yes? How did you convince them?

Immad Akhund: So generally speaking when you are a really big bank, you have a very different mode of operating. You have a whole big business that you're trying to protect. So having like a fintech company that's tiny that could grow but hasn’t even launched yet – there's nothing you bring into it.

To some extent, is it worth the effort to have online sign-up for non-US residents, right? And from their perspective, they're a big bank – they’re like “We don't even want to figure this out. This sounds scary.”

So most of the partner banks are smaller banks and often their business is partner banking. Their business is not their lending portfolio – most of their business is being really good at partner banking.They're willing to go hire compliance people. They're willing to go invest in that and figure out how to actually deliver that experience. So it's just a very different mindset.

I would say anyone who's thinking about fintech, especially when you're early on: avoid working with a big bank. You want to work with someone that'that wants to deliver a great experience to your customers along with you.

Turner Novak: I heard you mention somewhere else you have a 40-person compliance team. Maybe you just threw that number out, but that seems like a pretty big number for what I would perceive the size of Mercury to be. Is that a pretty big function?

Immad Akhund: Nowadays actually we have compliance and risk split out. For a really long time, no one could give me a straight answer of what the difference between compliance and risk is. Now I finally do understand it. I can try to explain it to you if it's useful.

Compliance is setting the product and the processes up so that they are complying with the law and with what you've agreed on with your financial institution partners and all that kind of stuff. It’s much more non-operational, like let's set up the things so that the right agreements are in place, we collect the right data, etc.

Risk is taking that and like applying it. So, let's take a concrete example. The compliance team with our partner banks have decided we cannot onboard a marijuana company. So when someone applies and in the description, if they say, “We deal with marijuana products,” then we have a separate team, which is the risk team, that looks at every single application and goes “Oh, actually this is a prohibited industry.”

If someone's trying to be tricky and they don't put in that they deal with marijuana products and they're like, “We provide like goods for sale online” then, then the risk team will go look at their website and go, “Okay actually they're selling marijuana products, so we can't onboard them.”

Those are the two different groups – compliance sets the rules that should obey the law etc. and risk goes and implements the rules. There are different parts of risk as well. There's card fraud – we have a whole team that deals with fraud. We have a team that’s called the financial crimes team, and they are literally talking to the FBI and a whole part of the Secret Service that deals with wire fraud.

Anyway, our compliance team is 10 or so people. And then our risk team is much bigger because they're dealing with operational stuff. And I think it's actually bigger than 40 now. It's like 60 or 65, something like that.

Turner Novak: So compliance is maybe like frameworks and then the risk team is executing on them.

Immad Akhund: Yeah, much more legal side of things. Our compliance team is under our general counsel, which is quite common as well. Very different mindset, but no one could explain that to me for a long time. I don't know why, maybe I was just being dense (laughs).

Turner Novak: Well when you're probably thinking about how your existing banking experience isn't very good, the last thing you want to do is learn all about why. It’s because of compliance or risk – things that aren't exciting to give people an even better experience.

Immad Akhund: No, I mean, actually I would say I was pretty interested in this aspect. If you talk to a lot of people and you say, “What sucks about your banking experience?”, yes they complain about “I can't find my account number and routing number on the website” or they complain about very specific product things, but a lot of the complaints actually come down to “I was trying to do X and I got blocked.” Or “I couldn't do Y” or “It took like days to do blah.” A lot of them actually are compliance issues. I do think it's a core part of what we solve.

We understand our customers really well, and then we try to apply technology and product to compliance and risk issues. We have what we call the risk team, but we also have a 20-ish person product engineering team that works with risk and compliance.

This is one of my other things that I like to do, which is I think it’s good for every major operational team to have an engineering team behind it. Same with like customer support. I think it's, it's actually a core part for every fintech service, but definitely for Mercury. A core part of our innovation is, how do we do a great job here?

If we go back to my earlier thing about how bank branches are kind of stupid and cost a lot of money, the other thing that's kind of stupid is the way most banks run, for compliance and risk, they mostly throw lots of people at the problem.

Yes, you need people to make like judgment calls on is this really marijuana or not, but I think like a reasonable amount of product can speed them up. Even if you take this marijuana thing, at some point maybe we'll build a scraper that goes and looks at the website and builds a little AI summary thing to figure out if it’s a marijuana company or not. There are lots of ways you can apply leverage to the system.

Turner Novak: Yeah. I'm trying to think of one example. When you go to your checking account on Mercury or you go to your card, the number is actually blocked out. There’s a click-to-reveal where it shows you your number and you can copy your card number. When I think about my existing personal bank, the numbers are X-ed out, so I'm assuming there are probably compliance reasons, like you can't show the information on a potentially public screen. Is that essentially how it flows through the product?

Immad Akhund: For most banks, the system that runs the website has literally no idea what the rest of the bank numbers are. I'm not even joking here. These systems are like a hodgepodge of systems that can't talk to each other and we insisted on building it all ourselves. Very few people of the bank care about making your experience better and giving you the numbers. There are definitely risk and compliance issues associated with it.

The other one that used to kill me and still kills me when I have to use a bank is, why can't you search for transactions more than three months old? You have to go into these PDF statements. It just pisses me off so much. I really thought for a while there must be a law because it's universal. Like every bank will stop you at three months. But yeah, there's no law – these systems are just like archaic things and no one's trying to improve them

Turner Novak: I have to ask this one question. We moved past it, but it's from a Saar at CRV. He said I need to ask about this, and this is maybe a hot topic that you’ve seen come up on Twitter. Remote work – so you guys are pretty remote-friendly, how did you make that work? Because a lot of people say it doesn't work.

Immad Akhund: I think there's a nuance to it. I don't think it works in a lot of situations but I do think you can make it work if you're very intentional about it. Firstly, pre-COVID, we were about 30% remote. And then post covid, we grew from 30 people when Covid hit to now we have 500. We were 400 at the start of this year.

We basically just committed to it. And I think it was hard to imagine hiring people with a restriction that you have to move to like San Francisco in the middle of COVID. And we had to grow. So to some extent it was not a choice. But then you have to lean into it.

So if you're going to lean into it, like how do you make it work? We do a bunch of things. It's not perfect. We have everyone get together at least four times a year. Being remote, it's not cheap. Paying for people to meet four times a year is a lot. Paying for office space is not that expensive.

It is not cheap, but you get the big benefit of like anyone across the US and Canada. And I'm trying to start hiring in Mexico as well. That's like hundreds of millions of people. And there's only a small percentage of people that already live in the Bay – I guess we could have a New York office as well – or they're willing to move.

The talent pool is huge. I'm in my bedroom right now. I like working from here. So I think that works pretty well. I think there are big downsides where it doesn't work, which is actually most companies, and I don't think it's that great.

My most controversial take is, I don't think it's that great pre-product market fit. I think most companies don't know what the hell culture is. I didn't know what it was in my previous company. I think most startups don't know what culture is and if you don't have a strong culture, you don't know what your culture is and you don't really emphasize and care about it, it doesn't work.

Whether you're a big company or small company, you have to have that kind of aspect. The third one is if you really scale, like if you're Google, when you're scaled up to be like a 30,000 person company before COVID, it's hard to change your culture to work for remote. I'm not a hundred percent sold that it works well at most of those companies.

If you add up all of those companies, like companies with bad culture, companies are pre-product market fit, companies that were scaled before COVID – that's like 99% of companies. So I do think the people that say on the internet that remote doesn't work – I think they have a point.

The reason it's a little bit of a culture wall is, if you are a CEO of a company trying to be a not remote company, you need all your employees to be convinced, and you need the talent pool to be convinced that they're willing to go back to this pre-COVID thing of moving their lives to come to you.

You have to try to win and you can't just make a choice for yourself. You have to try to win public opinion. It’s why people argue about it on the internet. They're trying to get people to change their mind about it. As a remote-first company, I actually don't really care what people think.

They should do whatever they want. I'm like, do whatever you want. I'm not trying to change people's minds about it. But actually, if you're an employee at a remote company or you want to be remote as an employee, you do want to change people's minds.

There's a little bit of a culture war happening between VCs and CEOs that want to have like a non-remote culture and employees that want to have a remote culture as an employee. It's just clearly, I think in most cases, better – most people want the flexibility to be able to apply from anywhere and do anything.

From my perspective, do what you want and it probably doesn't work for most people, but I think you can make it work.

Turner Novak: I think it's a phase of life and phase of career thing too. Like if you're super young, no obligations, you would probably move to San Francisco or move to wherever and work in the office.

Immad Akhund: We have an office in San Francisco and one in New York and one in Portland. I think there is a reasonable number of people that would prefer being in an office.

Frankly, if I just came out of college, I don't want to be sitting in my apartment in New York all day. I want to be around people and making friends and working in that environment. We try to be a little flexible, but I would say we are remote-first rather than hybrid. Most of the meetings people have are on Zoom.

Turner Novak: On the other end, when you have kids, that's a big piece. You're like, I need to be as efficient as possible with how I spend my time.

Immad Akhund: It's nice to have some flexibility, right? You're likem I need to go do this chore. You can just go do it for 20 minutes and come back to work. If you're in office, it's hard to have any flexibility.

Turner Novak: So where do you think the mistake is made then in terms of remote work? It’s almost like not choosing the right workplace strategy based on the position that you're in as a company or concept.

Immad Akhund: I think the biggest mistake that people made and they are getting screwed by it. Take a company like Apple – and I was talking to an Apple employee recently – they said you can go remote, but you have to come back once COVID is over. They were very deliberate about it and everyone understood it. But I think a lot of companies were either non-specific about it and they didn't set a policy, or they actually set a policy and said “Remote is fine,” and people moved away.

They moved on with their life thinking remote was fine and now they're trying to change that. I think that creates the most anger among people – where now they don't live in the Bay Area or wherever and are expected to move back or lose their job.

And I think that kind of expectation setting and breaking is probably the biggest issue for people, and it's a very valid and relevant issue. And then I think the rest of it comes down to like people trying to change people's minds.

Turner Novak: Slightly switching gears in terms of fundraising, you do this program, it's called Mercury Raise. Essentially you help startups raise money. Can you kind of talk through really quick what it is, how it works, and maybe we can talk a little bit more about fundraising tactics?

Immad Akhund: Yeah. We're going to change it around so this is going to be old information soon but right now we run it once a quarter. You can apply to it. We run it for free. We have about 3,000 applications to it, and we select about 50 companies using internal and external judges that help select the companies.

And then we blast those 50 companies out to a set of investors. I assume you are on it, Turner, so we have a bunch of mostly seed, pre-seed investors that we send it out to. The idea from the investor perspective is that this is a curated list.

We source most of these companies from Mercury customers, and most people sign up to Mercury right when they've just started their company so we have a source of early-stage companies. It's actually hard from an investor perspective and this is I think partly why YC is so successful. A lot of the time as an investor you're waiting for like deal flow to just present itself, or you have like you have your Twitter DMs or something, which is like completely uncurated deal flow.

Those are the two levels mostly in the world. It's like completely uncurated, really hard to find, very noisy dealflow, and then the other side is very curated, but very passive, like you're waiting for introductions from other investors and things like that. We wanted to create a channel, which is a lot more signal but also anyone can get to it.

Turner Novak: I always look at the list! It’s valuable.

Immad Akhund: Oh, nice. Have you invested in much through it?

Turner Novak: I've had portfolio companies that have got gotten checks through it, so I know it definitely works. I feel like you guys have some success stories. I think it says on the website like $1.7 billion raised or something.

Immad Akhund: Yeah, that might be a little bit of a vanity metric of all the money that all the Raise companies have raised. I do think for the 50 that get selected, it's quite valuable.

And this will come back to your fundraising point, like fundraising at seed stages is all about momentum. Maybe at every stage, but especially at seed stage, because – there is this game theory perspective where an investor's incentive is to wait as long as possible because every month you wait, you get an extra piece of data. You also have this massive disincentive as an investor that you don't want to be the only check in the round.

That's happened to me a few times where someone's like, “I'm raising $2 million.” I'm like, “Sure, I'll give you like $50k” and then they end up raising $200k and they don't have enough money to make that startup successful. So my 50 K is just like this orphan.

And in 2021 it didn't matter because everyone was able to raise whatever the hell they wanted. But you know, right now and pre- 2020 it was a factor that you don't want to be the only one in the round or you don't want the round to not be complete.

With the combination of those two factors – you get more information over time and you don't want to be the only investor – it means that the incentive for investors is to wait. So the only way the founder can break this incentive is to to talk to so many investors that you create this like moment that's self-fulfilling.

Turner Novak: So how do you do that?

Immad Akhund: In general it's hard, but if you're using Raise Seed by itself, it's maybe not enough. We send you to 500 investors. But if you're using it in conjunction with the round, it can help give you the extra push.

How do you do that? I think step one, which I think a lot of early entrepreneurs miss is, you want to have a really good network of entrepreneurs. So I think sometimes people try to build a network of investors. I think that's actually much harder as an early entrepreneur. But knowing a lot of entrepreneurs is not that hard.

You just show up at events you like. Most early entrepreneurs are willing to be helpful. Everyone's been through their journey. You find people that are like close to your space. Ideally you go through YC or something like that and that helps a lot. So that's step one.

Because most entrepreneurs that have raised a seed round know at least 10 investors, if you know 10 of them and they know 10 investors, that's a hundred investors right there. And most of the time as an investor I feel like you almost have a legal obligation to look at an email from a portfolio company founder, right? Otherwise, like, what the hell are you doing?

So I think that's step one. You want to have a good network of entrepreneurs that can connect you to investors. And then step two is, you get all your ducks in a row. You write the deck, you go pitch it to some of your friends, you pitch it to your wife, whatever. Make sure that you're like pretty solid story.

Two-weekYou try to de-risk it as much as possible to make sure you’re selling a good product to investors. And then I try to compress it all down into like a two-week period where you just go completely crazy. Ideally you're doing like five meetings a day for two weeks. So that's like 50 meetings.

With that kind of momentum, I think your pitch, at least when I'm pitching something, just gets better and better if I do it again and again in this very quick time period. It’s because they'll ask you questions and then eventually you get to a position where you've just memorized the pitch.

You can completely focus on what the investor is saying. You don't need to think about what you're saying. And that’s a very different mode of operating versus actually I'm pitching and I'm trying to remember what I was supposed to say at this point.

Turner Novak: They asked the wrong question and it threw you off.

Immad Akhund: Yeah, exactly. You want the page to be automatic and you want to be focused on actually answering when an investor asks you a question. You don't want to answer the question you want to answer – what’s the question they're trying to ask?

If the investor's like, “How will you get your first user?”, you don't want to answer, “How will you get your first user?”. You want to answer it with “Hey, my distribution strategy is X. I'm expecting my CAC to be Y” and you don't want to answer the literal question. You want to answer the question behind the question.

It's hard to do that when you're like very focused on the pitch part. So that's one part, your pitching gets way better. And then the second part is you can build up this momentum. If you do 50 meetings and all of them said no, you’ve probably got some issues anyway.

Even if your hit rates is only 10%, that would mean that in the first four or five days, you'll get three or four commitments. And then the next week you do the pitching, you're like, “Hey, blah is in and blah is in” and then you've got momentum. And then the second bit of like the investor mindset kicks in, which is FOMO [“Fear of Missing Out”]. And that's where you need to create to get a seed round done.

I don't think very many seed rounds get done without some FOMO. You want the investor to go “Shit, this round is happening. If I don't jump on the train, I'm not going to get my allocation. I'm not going to be able to invest.”

Turner Novak: So do you recommend talking to your favorite? Let's say you really love Saar at CRV. You want him to join your board. Do you go to him first or do you go later?

Immad Akhund: I think the ideal is to try to aim for the middle. It’s hard to do this. You want to have your least favorites upfront so you can practice, you want your most favorite in the middle, and then you want the rest at the end.

That's the rough thing. You don't want the most favorite at the end because there might not be enough space in the round for them. And you definitely don't want to have the start because your pitch sucks at the start. Until your pitch is tested, it will suck.

Every day you should do the pitch and you should say, “Okay, this is what I screwed up. This is why I need to change about the story, the deck, etc. This is the questions I need to answer better.” You should be learning from this process. It is intense, but it shouldn't last more than like four weeks.

I would say if you don't have like significant momentum after four weeks, the reality is as an entrepreneur, you do whatever the hell it takes. But in the ideal world, you would stop, you'd go “Okay, I'm just not there yet. I'm screwing something up.”

Either you need to get more product made, you need to get more customers you need to significantly change your pitch, maybe your valuation's coming in way too high. Hopefully you figure that out way earlier than like four weeks in. But ideally you can step back from it and then re-approach the whole thing after six to nine months.

I think that gives you enough time to make progress and like you can re-approach the same investors after six to nine months and say, “Hey, this is all we've done. This is what you said, this didn't work, etc.” You can't really come back to them like after a few weeks because when someone says no, it's hard to get them change their mind.

Turner Novak: Yeah, I've actually made two investments where I didn’t invest in the pre-seed. They did get the round done and they came back to me and basically both times I said, “Eh, I don't even think this is possible. Really cool idea, but I don't think it's going to work.” And then they come back, “Hey, we've kind of got it to work.” And I'm like, “Shoot…”

Immad Akhund: Six months later or something?

Turner Novak: Yeah. Like, nine – six or nine months, exactly what you described.

Immad Akhund: I think every investor does that, right? Like when you pass on a company, you're never sure, right? This is a game of unknowns. Sometimes I'm pretty sure I'm like “I just don't even care what this person does.” But a lot of the time, I don't know, there's some part that I'm not sure about. And with persistence, if someone comes back and they're like, “We did this stuff,” and they actually did it, that already puts you in the top 10% of entrepreneurs that you're doing things.

Turner Novak: So where do you think people usually trip up throughout that whole process? Is there like a certain part of the funnel or a certain step where they just don't do it correctly? Where do you see the most mistakes?

Immad Akhund: Everything. People make mistakes on everything. I mean, I made all the mistakes, right? I think the fundamental mistake is like having a product that's having a non-venture scale startup. Not every company should get funded by investors.

Investors are aiming for this fairly unusual company that could have like a 100x return profile. That's just the game being played. And not every company should be playing that game. That's probably the most fundamental mistake.

I think the one that I have made that I think is a little subtle that I try to convey to people – it's kind of hard to learn – is if you're doing like 50 meetings in two weeks, it's very easy to treat the investor as like a transactional player. I need to sell you and you need to believe in this sale. And you don't want to be a salesperson which is weird because you are selling something, but somehow in this short 30 minute to one hour time period, you have to build a connection.

At the end of the day, when a founder emails me, I will respond to them. That's a big commitment that most investors are making – they’re investing in this relationship as well as in the company. So you want to try to not be very transactional about it.

If I talk to someone and they're obviously trying to create FOMO, they're like, “Blah, blah, blah is in, and you better make a decision quickly.” It's just so off-putting. I'm like, “I don't want to work with this person.” And there are so many ways that people do think of it too much as a sale and they don't think about it as a long-term relationship.

So ideally you spend enough time getting to know them, explaining your story, and just not being a jerk. You don't want to be a sales-y person because most investors see hundreds of these pitches, right? That's most investors' jobs. It's just so easy to say no when someone's a bit of a jerk.

You don't even have to like, pay that much attention to the rest of the pitch. It's just like, “This person is selling things and it's too much ego” or “I don't even know if like they're lying about this.” You don't want to have any of those red flags. Those are the easiest ones to lose an investor on. I think especially for early fundraisers, it's very easy to fall into those traps.

Turner Novak: Yeah. Do you have any embarrassing mistakes that you've made there? Any stories you can share?

Immad Akhund: I have one really embarrassing story… So check this out. We were raising our seed round for Mercury and I talked to Alex Rampell who is our GP on a Thursday, and he really likes the pitch. He's like, “Come in on a partners’ meeting on a Tuesday.”

I've told Alex this story. Whenever I went to a partners’ meeting on Sand Hill Road, there's a Starbucks right there. And I had a little ritual where I'd go to the Starbucks, I'd show up early, I'd go to the Starbucks, get a latte, get settled in, and then I'd go. So I did that. But obviously like I'm a little nervous about this.

So I didn't put the lid on my Starbucks coffee properly and it’s loosely on top. I pick it up and I'm with my co-founder Jason. I go like this (gestures), and it falls all over me. This is like five minutes before this pitch and there's no time to go fix this thing.

Luckily it was a gray-ish shirt, so I'm wearing a gray-ish t-shirt and I have a massive brownish latte stain that's half of the shirt. And I'm like, “Wow, this is going to be awkward.” I don't even remember if I had a jacket. I don't think I had a jacket to cover. I had nothing to cover it.

So I walk in and thank God they have the whole room dark because they had the screen up for the pitch deck. The whole room is like dark. I'm still very self-aware that I’m half wet and it's going to look weird. But the whole room's dark and then I do the pitch, and then people ask me questions. But Marc Andreessen is there and he's just completely quiet through the whole thing.

I'm like, maybe this is a disaster, because obviously, Marc Andreessen's the man here, he's the only one who's got this printout of the deck and he is making notes. I don't even know what he's doing. And then he lets everyone ask all the questions and in the last 10 minutes, he’s like, “Okay, let's go” and then he asks tons of questions.

Turner Novak: Do you remember what he asked you?

Immad Akhund: You know, this is like six years ago and I was probably more worried about my latte stain, so I'm finding it hard to remember the exact what they asked. But I mean, I don't think there was anything that was a super surprising question. It was like the standard set of questions.

Marc Andreessen and Andreessen Horowitz in general were very focused on how big could this be.That's their big thing. How could this be a $100 billion dollar kind of thing? With Mercury, it was easy to paint that picture.

They gave me a term sheet that day, so it worked, but it was the most embarrassing kind of moment going like, “I don't know whether this is going to work” and I’m walking in with this thing.

Turner Novak: Did anyone notice?

Immad Akhund: No one commented on it, so I don't know. Maybe they did and they were just nice about it. But, yeah, it worked.

Turner Novak: That's amazing. Was it hot coffee or cold coffee?

Immad Akhund: Hot. It was very uncomfortable when it happened.

Turner Novak: I'm glad you made it through. This isn't quite the smoothest transition, but I know we both really want to talk about this. AI – it's the big topic right now. I'm assuming there are probably ways you can incorporate it into Mercury. I know you're kind of an investor. How are you kind of thinking through all the AI stuff that's going on right now?

Immad Akhund: One thing that's interesting is I don't think fintech has a ton of great AI applications. I do think things will get more efficient, like customer support is an obvious one, where I think AI will help answer the first 80% of questions or something like that.

And maybe with fraud as well, you could apply it, but AI has been applied to fraud for a long time, so maybe there are some extra things you can do. For fintech and probably for a reasonable amount of businesses, the biggest application is efficiency gains, and maybe our programmers will get more efficient and write code faster.

It is a little sad. would love to come up with like, some really sick application and blow people's minds. But yeah, I’m a little skeptical and doing it for the sake of doing it. It has to have its own really interesting thing to it.

If you look at a lot of people announcing things in AI, especially existing companies, it's kind of forced, right? They want to jump on the bandwagon and do it. And that's not really our style.

Turner Novak: Yeah. We've seen that play out every hype cycle.

Immad Akhund: Every hype cycle. One thing that I think is funny is we just got through this crazy 2021, like everything was a hype cycle phase, and it's just so funny that we're back in 2023 and we're making the exact same mistakes.

Companies getting funded with no revenue, seed valuations at $40 million. I'm like, “We just learned these lessons, why can't we just like remember them for any time period?”

Turner Novak: It always happens. It just happens over and over again.

Immad Akhund: I do think greed is a much more powerful motivator to human nature than fear. And I think this is just one of the parts of that. But yeah, I think there are lots of interesting things. I think there are two types of companies that are interesting. And if you're not one of these two types, I would probably not touch AI.

Number one is like you actually know what the hell you're doing, like you've done a PhD in AI. You're at the cutting edge and you can do something that doesn't have to be a foundation model, but something more foundational that really pushes the field forward.

And especially if you can – there's a bunch of people doing vector databases[3] now – iff you can build some of these picks-and-shovels companies that are really potentially foundational, I think it’s an interesting space. But there are not that many people in the world that can do that.

[3] Vector databases store data such as text, video or images that are converted into vector embeddings for AI models to access them quickly. (More here)

And I think the second type that's interesting is people who have this very specific deep knowledge about their space and can apply these modern technologies to it. To come back to like this use case, the customer service use case, I think probably Intercom or one of these other existing customer service companies that have all the data, all the users will probably successfully apply AI to their use case.

It seems surprising that it'll be a new company that does it. But outside of that, if you are a doctor and you deeply understand the process involved and talking to a patient and coming up with a diagnosis and like you want to go code that into an AI thing that doctors use or something like that – just making that example.

There are a lot of like knowledge systems that I do think either will be replaced by AI or be significantly improved by AI. And if you deeply understand those systems, hat would be a great like startup to start. But most of the obvious ones, there's going to be a hundred startups doing it as well.

I actually think the contrarian thing to do is start a non-AI startup right now, and you'll almost have like no competition and you can own that space.

Turner Novak: I kind of think about it as if you're doing a startup in AI, you have to go after like customers that don't have software yet. And the AI is almost the reason they might adopt the software.

Immad Akhund: What’s an example of that?

Turner Novak: I don't know, like education or a landscaping business or factory software, software for the real world. Google, Facebook, Salesforce, insert the long list of existing software companies that have a ton of customers might be like, “Cool, we made this AI chatbot. We're going to put it in front of everyone and they're going to use it.”

But if someone's not a customer of those products yet, because no one's ever built software for them, maybe that's the opportunity. It’s categories that no one really talks about. That's kind of how I think about it.

I also think the big winners will be the Googles of the world. They're probably going to add a trillion dollars in market cap related to AI over the next 10 years.

Immad Akhund: I think Facebook maybe, but I think sadly, Google is in the business of slowing you down to some extent. They want you to click on ads. I think there's something about getting an answer quickly that's slightly disruptive to Google.

I don't know if they'll adapt as much. I do think Microsoft is like probably the most likely to add the highest kind of amount of market cap because of this. Who knows? Maybe Google will.

Turner Novak: That was probably the right company to put in there – Microsoft, not Google. Google, what are their big products? You've got Google search, which everyone is kind of starting to chip away at. You have YouTube, which TikTok is starting to chip away at. I mean, it's a pretty serious competitor. You've got Chromebooks, Microsoft is kind of putting pressure there. And then they have cloud too, but again, is Microsoft beating them in cloud too? I don't know. I'm not an expert on Google’s business.

Immad Akhund: Yeah I feel like they’re the third, behind AWS and Microsoft on cloud.

Turner Novak: When we first met, it was on a panel where I think we talked about crypto and this was right before FTX. How do you kind of think about how crypto interacts with the finance system and with banking?

Immad Akhund: Just being around Silicon Valley for this long, I was very excited about crypto like 2011, 2012, 2013. It felt like the future, like a system that no one controlled. And you were like, “Okay, obviously transactions will get cheaper and faster” and all of this stuff.

Now I guess sometimes people think of fintech and crypto as the other side, which to some extent they are, but I don't think they're strictly are.

Turner Novak: You mean like two different systems?

Immad Akhund: No, like almost opposing systems. Fintech is trying to fix banking from the inside, whereas crypto's trying to fix it from the outside. And you realize actually, a lot of things that people complained about with banking exist for a reason. You don't really want your money to be sent somewhere and have like absolutely no way to recover it. That might sound good, but actually, most customers don't want that.

They want to be able to shop and be able to dispute that transaction. They don't want to be like “I sent $50 in crypto and I'll never see it again.” Or “someone stole it and there's no way to get it back.” So a lot of the things that people think of as frictions exist in the banking system like customer protections.

That’s the tradeoff being done there. I also think that a lot of the promise of instantaneous payments was not really delivered by crypto. It takes 30 minutes on most things, you can't make enough transactions.

Their fees are actually really expensive – Mercury fees are cheap for any payment. Actually, they’re free for every payment type apart from international. In crypto, you get charged a lot of fees. So having said all of that, I do think there's two strong use cases for crypto.

Number one is just to store value, which Bitcoin covers pretty well. I think Bitcoin in most ways is better than gold, for that. And then I think USDC is actually quite good to transact with and hold. Most other currencies in the world with some exceptions are more volatile than USD, and international payments are really painful so sending and receiving USD instead of like having to deal with the SWIFT network is probably better.

Turner Novak: Can you explain what that means? Just for somebody who maybe doesn't know what USDC even stands for or anything you just said?

Immad Akhund: Okay, so you know Bitcoin and Ethereum and all of those are like tokens. There are a few tokens that are pegged to various currencies.

Turner Novak: And these are basically like cryptocurrencies, like the US dollar, but on the blockchain.

Immad Akhund: On Ethereum or whichever blockchain. So you can have an Ethereum wallet either on Coinbase or some other tool, or you can have it locally on your desktop. And that can have this token, in this case, USDC – this was founded by Circle and Coinbase. And at any point you can go to Circle and Coinbase, and sign up to them and transfer this USDC token into USD. Or you can transfer USD back into USDC.

Because they hold the money and they're not supposed to loan it out or anything, they're supposed to put it in a safe place, there's a one-to-one matching where at any point you can convert between USD and USDC.

Turner Novak: So it's not fractional reserve like the banking system. It's literally one-to-one. The money in theory is always there.

Immad Akhund: Yeah. There are a few people that do these stable coins, they're called. And I would say USDC is – I don’t know if it's quite the most popular, but I would say it's the most trusted and regulated. But once you have it, it's quite nice, like you can use it at these exchanges, but you can also send it to anyone in the world.

Turner Novak: And you can convert two different currencies like the Nigerian Naira or Euro or whatever country.

Immad Akhund: Well, kind of. There’s EUROC, which is a stable coin in Euro, so you can convert easily between that. But I don't know if there's a good Nigerian Naira stablecoin.

And on the other side, you still need an off-ramp. So if you're sending it to Nigeria, it might be hard to convert it from USDC to like the local currency, but again, if you're sending it to the US or Europe or whatever, it's not that hard.

I think the big bit that this solves is that international payments are really painful. We do them at Mercury and it's very archaic system, how you send money between like different countries.

We don't support them right now natively – like you have to go use Coinbase or something else to use it with us, but I do think it's like an interesting use case for crypto that Mercury would eventually support.

Overall, like I do think Crypto in general used up a lot of its like hype cycle merits. People just keep expecting things from it and a lot of people just promise a lot of things from it. And now we are 13 years in, and the promises have not been delivered.

So maybe in the next hype cycle, we'll have the promises delivered. And maybe some people would argue that that's a little further on. But I do think you can only use this hype cycle so many times. I think a lot of crypto entrepreneurs overpromised and underdelivered.

Turner Novak: Yeah. Well I feel like that's kind of the beauty of how the Silicon Valley ecosystem works, is you use the hype cycle to raise capital to then actually build and execute something that does solve a problem or does become a real company.

Because to your point with momentum and FOMO, every big publicly traded company at one point was a startup and whether or not they raised venture capital, they all need to get started somehow.

Immad Akhund: One of the flaws in crypto, which hopefully you'll appreciate is that I think the powers of like a private tech company are that you can't sell your shares. So when you buy in as an investor and you buy in as an employee, it's just long-term. There is some greed behind it, but you really have to believe in the mission and the vision.