🎧🍌 The $4 Trillion Business of Financial Crime with Natasha Vernier, Co-founder and CEO of Cable

How financial crime makes up 4% of global GDP, why we only catch 0.2% of it, why banks aren't incentivized to stop it, joining Monzo as the 17th employee, and how to get VCs to pre-empt your Series A

Stream on:

👉 Apple

👉 Spotify

The episode is brought to you by Secureframe

Secureframe is the automated compliance platform built by compliance experts.

Thousands of customers like Ramp, AngelList, and Coda trust Secureframe to get and stay compliant with security and privacy frameworks like SOC 2, ISO 27001, HIPAA, PCI, GDPR, and more.

Use Secureframe to automate your compliance process, focus on your customers, and close deals + grow your revenue faster.

To inquire about sponsorship opportunities in future episodes, click here.

Natasha Vernier is the Co-founder and CEO of Cable, the all-in-one effectiveness testing platform for financial services. Prior to Cable, Natasha joined UK neobank Monzo when it had less than 100 customers.

She built and led their financial crime team for five years, and is one of the most knowledgeable individuals in the world on financial crime, which amounts to over $4 trillion per year, or 4% of global GDP.

Natasha started Cable in 2020 with her co-founder Katie Savitz, and has since raised over $16 million supported by investors like LocalGlobe, CRV, Stage 2, and Jump Capital.

In this episode, we discuss:

How crime is a $4 trillion market

Why we only catch 0.2% of financial crime

The reason banks are incentivized to stop fraud, but not crime

Why it's so hard to stop financial crimes

The $20 billion in crime committed on crypto rails in 2022

The fastest growing types of fraud

Joining Monzo as one of the first employees and staying through a $4 billion valuation

What it’s like to be fully invested in a startup when you’re not a founder

Building Cable to enable regulatory and financial crime teams

Signing the first customer and raising a Pre-Seed round without a product

Why compliance officers want to buy complicated products

How Natasha diversified her cap table, raising a Seed round from CRV and a group of angels with broad skill sets, ethnicity, race, and sexuality

How she got two funds to pre-empt her Series A

Why founding a startup means getting punched in the face every day, and her biggest mistake was not enjoying the little things early on

The two founders she most looks up to

The one interview question she asks every candidate at Cable

Follow Natasha on Twitter and LinkedIn

🙏 Thanks to Zac and Xavier at Supermix for help with production and distribution.

Transcript

Find transcripts of all prior episodes here.

Turner: Natasha, how's it going? Thanks for joining me today.

Natasha: Yeah, good. Thanks for having me, Turner. Good to be here.

Turner: I'm really excited to chat because your company is operating in the space of financial crime. Can you explain what that is and why it's important?

Natasha: Yeah, to clarify, we're in the anti-financial crime space. We're not trying to perform the financial crime ourselves, although it sounds better that way. My job title and my previous job was Head of Financial Crime, which I think is the coolest job title ever, but also slightly wrong, because I was not trying to perform financial crime.

Turner: You're not committing it.

Natasha: Correct. I promise. We're trying to help companies become more effective at stopping financial crime. So we mostly sell to banks. Financial crime is the movement of money, trying to utilize money that has been gained illegally. So if you carry out a crime, you're almost always doing that to try to have some kind of financial gain.

You steal something, you're trying to get some money from somebody else, you're trying to sell drugs. They're all doing that to make money. And so financial crime is really, “How do we then take that money that I maybe made illegally and actually use it? How do I embed it into the financial system? How do I buy my house with it? How do I buy that boat?” All of that stuff is financial crime. So it's the getting of the money illegally. It's the moving of it, and it's trying to use it.

Turner: And I think you've said you think it's the biggest problem in the world that no one's talking about.

Natasha: I just don't think anyone really knows about it, right? Before I started working at Monzo and was asked to deal with the fraud that we were seeing, I just didn't understand really what it entails and how big a problem it was. And I remember saying to my family, “Oh, I'm doing this new thing. It's cool. Financial crime.” They were like, “Oh, fun. What does that mean? Do you find a criminal, what, like once a week, or once a month?” I was like, “It's happening all the time and nobody knows.”

Turner: The number, if you go to the Cable.Tech website – $4 trillion dollars a year in crime? That sounds like a fake number.

Natasha: It's crazy. The UN estimates that 4% of global GDP is being laundered every single year. It's so much money. It's one of the biggest economies in the world.

Turner: How do you define crime? What goes into that $4 trillion dollar number?

Natasha: It's a lot of things, which does make it difficult to then pin down, but it's everything from drug-trafficking to environmental crime, ransomware, corruption. It's the little scams that you see on social media, all the way up to the huge organized crime rings, selling drugs across borders, and the big headline stories, so it's all of those things.

Turner: And I think you've said that basically the majority of this crime is happening for financial gain.

Natasha: Most crimes are committed to make money. And so I was coming up with this, I called it the financial crime equation. I was looking at the Office of National Statistics in the UK. They list out what crimes are carried out every year. And it lists out fraud, all these different types of crime.

If you actually look at, “What is the purpose of somebody stealing something? What is the purpose of a robbery or a theft?” They're all to make money. They're all to get something that they can then sell to have a financial gain.

And when I ran through that list that the ONS put up, over 80 percent of those crimes, ultimately the purpose of them, was to make money. And so if more than 80 percent of all crime, just crime generally, not financial crime, is being carried out for financial gain, to be able to use that gain actually in the financial system, to buy your coffee or to buy a house, you have to perform financial crime.

This is the biggest problem that no one talks about. All of this crime is happening, it's all for financial gain. And financial crime is the thing that you have to do to then be able to use all that money.

Turner: And I think I've heard you say before, if you're committing some form of theft, or local police are trying to track someone down or stop certain crime from happening, it's all tied to the financial system. So I've heard you propose, “We should stop the ability to do it on the financial end, and that will actually stop the original source of the crime.”

Natasha: Yeah, that's how we think about it. That's a bit of a hypothesis that we have. So, in all those movies or TV shows, it's always like, “Follow the money.” That's true, right? You have to follow the money and, be that digital or fiat currency, whatever it is, somebody is carrying out a crime to make a financial gain.

They then have to move that money, get it into the financial system. If you follow all of those crumbs that have been left, and you make it harder for somebody to actually utilize the money that they have stolen or the gain that they've made, then they're not going to carry out the crime as much, right?

If you're not making as much from the thing that you're doing, you just won't do it as much. You'll find other ways to make money. So if we can actually make it harder for criminals to use the gains that they make from their crimes, if we become more effective at stopping financial crime, then less crime will happen.

Turner: The UN estimates we only catch like 0.2 percent of all this stuff. Why can't we catch it?

Natasha: I think there are a few different things that go into that, a few reasons why it's really hard to stop, and why we're bad at it. Some of it is traditional structural issues with banking, and how traditionally slow banks used to move, right? They're just huge, huge, huge organizations with very, very old technology.

They were also not incentivized to stop financial crime. All banks are incentivized to stop fraud because it hits their P&L. If somebody carries out fraud, a consumer loses money, very often the bank will pay that back and the bank will be the one to take the loss.

And so if there is high fraud at a bank or a fintech, then that financial institution is the one directly impacted. This is why all the fraud in the UK that was happening to fintechs like Revolut and Monzo and in the US with Chime, that's why that was such front page news, right? It's actually impacting their bottom line.

How can you IPO, how can you become a profitable business when your fraud rates are so high? But the other types of crime that are much more prevalent and fill up much more of that 4 trillion bucket, the money laundering, the drug trafficking, the corruption.

The requirement that banks have is to identify suspicious activity and then to report it. They are not financially incentivized to stop it. And so that provides a weird imbalance in the incentives that banks have traditionally had.

And what's really interesting, I think, and the question that we often get asked at Cable, is why would anybody want to buy Cable if it tells them how much more work they have to do to become effective at stopping this? And what's really interesting, there's a whole load of reasons why they should buy Cable that we can talk about later.

But I think that people are changing. There have been some surveys done of consumers, and a large number of consumers care if their bank has knowingly been involved in financial crime or, people cared that their banks had banked Trump or Epstein. People didn't want to bank with those banks because they didn't want to be connected to that kind of attitude or those kinds of stories.

And I think we're seeing a little bit the generational shift around climate change. People care more about what they do with their time, where they shop, who they spend their time with. I think people also now care who they bank with and what that says about them, and the impact that it can have on society.

Turner: What's the process then, like if I'm a criminal, what am I usually doing to get around these certain controls? Do the banks just not watch closely and it's pretty easy to commit some of these certain types of crime? Or how does it usually play out?

Natasha: There's a whole range, right? So you've got the individual criminal who is sitting in his bedroom or her bedroom and that he or she creates a scam on Facebook, selling Air Jordans for like $1,000 or something, and those don't exist, and they make $1,000 and then they just disappear.

And then you've got the middle-of-the-range-type crimes where maybe you've got a small enterprise, a small group of people who work together to carry out crimes. And so you might have somebody who is controlling a group of what we call money mules. And a money mule is somebody who is being used to launder money, maybe without actually knowing that they are being used to launder money.

So an example of this, this really spiked during COVID. People obviously were on furlough or had been made redundant, at home spending a lot more time on social media, in need of money, in need of easy ways to make some more money. There were lots of adverts around, “Become a payroll provider for our nursery.” And you're like, “Okay, I can do that. What does that mean?” You look at the details. It says, “Work for us from home, from your sofa, two hours of work a day, and you'll make 500 pounds,” or whatever it might be. They may have to actually send in their passport and go through an interview process to get this job.

And what the job is, is “Okay, so you're running payroll for our nursery, or our childcare program. You will receive payment, and you need to then pay all of our teachers.” So you'll receive a thousand pounds or a thousand dollars, then you send out a hundred dollars to these nine people, and you keep a hundred of that, and that's your payment.

And you're like, “Okay, cool, well I went through an interview process, I provided my passport, or my work documentation, and I'm moving this money for this company that I can Google, because they're on Companies House in the UK, or they're registered somewhere.” And that person has become a money mule, and they are receiving illicit money, illicit gains, gains that have been made from carrying out a crime.

They are sending it on to maybe nine other money mules that don't know what they're doing, or maybe back to the criminal enterprise itself. And they are keeping a hundred dollars or a hundred pounds, but that is criminal money. Now that was a really common way that people became involved in money-muling during COVID.

And what's even smarter about this crime is that they've also handed over their passport, right? So probably that criminal enterprise is also carrying out fraud and signing up for new bank accounts as them. Because they've spoken to them, they maybe have taken a screenshot, they can have their passport, they can go through an identity verification process for a fintech or a bank. So it's a multifaceted crime. That's a middle-of-the-road, but still organized, crime.

Turner: I'm assuming this nursery doesn't exist.

Natasha: Nursery does not exist. But if you use something like a nursery, or childcare, or a school, or a hospital, then you think it's legit, and you go through an interview process, and so on, and so on.

Turner: So then what's the bigger scale?

Natasha: Well, the big stuff is the Pablo Escobar, like, huge drug rings where you can literally think of them as large corporate entities. They consider themselves to be companies. They probably have a finance department. They probably have a CFO. They probably have a marketing team, people who are very, very skilled in accounting and in actual legitimate jobs, but they work for criminal enterprises, and their whole job is, “How do we move money around the world and spend it on stuff and avoid being caught?”

Those cases, I think you probably have less and less confidence that you'll ever catch them. If you stop money, you don't know whether it's from a huge ring or from a middle-of-the-road-type criminal gang.

When you're working in a bank and you're seeing these money movements, all you have to go by, if you're working in a single bank, is, “Okay, I see this money coming into this account that belongs to Joe Bloggs. And the money is going somewhere.” And so firstly, “Who is Joe Bloggs? What information do I have on them?”

And then the only other information you have is, “What do the normal transactions coming in and going out look like? And does this look the same? Does this look genuine?” And so you're trying to piece together this story and work out whether what's happening is actually suspicious or legitimate.

Turner: What are the tools or the strategies that people use? Is it spreadsheets? Do they work with the FBI or Palantir or something? What tools are out there? And maybe we can talk pre-Cable, because I know you're solving this, but how did they historically do it?

Natasha: Almost all of the financial crime investigators that I've spoken with or worked with on that, would love to be able to speak with the FBI and actually be able to be involved in finding these criminals. But disappointingly, you never do. Job actually stops when you send off a report. And then you hear nothing, or certainly that's the case in the UK.

Turner: Because you have a front row seat of, “We see these transactions happening.” You would think that piecing together all these different parts of the chain would make it easier.

Natasha: Yeah, you'd think. That's what the government entities are doing. So that's what the FBI, or in the UK, the National Crime Agency, that's what they're doing. They are trying to piece together, “Okay, I've received this one report about Joe Bloggs from Bank A. I've received this other report from Joe Bloggs from Bank B. I'm going to try to piece together all that information”

The tools that people use, how do they actually stop it… Is it spreadsheets? So, it might be spreadsheets when you start a company. When we started Monzo and we had our first, what they're called transaction-monitoring rules - so you'll be monitoring transactions to try to identify suspicious behavior, because you simply can't look at all the transactions, of course.

The first way that we did that was in Looker, just with some simple rules, pulled together once a day, a list of user IDs that deserved further investigation. And then we migrated that into an internally-built, transaction-monitoring system. There was machine-learning in there. There were rules-based rules.

And there are lots of very good transaction-monitoring vendors out there that people buy. So Unit 21, ComplyAdvantage, Oracle AI, all of those types of companies do this, and they all use a variety of rules-based rules and machine-learning rules.

Turner: So do you know what they look for? Are there certain patterns that trigger a crime, fraud, burglary, human-trafficking? What are the signals that trigger this stuff?

Natasha: They're looking for a mixture of known typologies. Typologies is the term that we use to talk about a particular series of events or actions that could indicate a crime, and I'll give an example in a second. But they're looking for a mixture of typologies, but also unusual or anomalous behavior.

So, if I, Natasha Vernier, I'm always receiving about this much money in per month, and I'm spending that, if I suddenly receive a lot more, that might be flagged as an anomalous thing that somebody might look into at the bank, and try to understand if it was legitimate. But typologies is what's really, really interesting.

So a typology, as I said, is a series of events or actions that a customer might take, that could indicate that a financial crime has taken place. So, for example, there is a typology in the UK, if there is a male in their early to mid-twenties, they live in or around an area of England called Birmingham, and they spend money late-night and early mornings on Eastern European airlines, and on larger-than-average spending at fast food restaurants, like a KFC or a McDonald's, and taxi companies. That is a typology that could indicate that that person is involved in human trafficking.

Now, of course, not everybody who does those things, who buys a flight to an Eastern European country or spends money at KFC, is involved in human-trafficking. But we know that generally, a series of events like that may indicate that that person is involved in human-trafficking.

Often women are trafficked from poorer Eastern European countries, and they are brought to places like England. And then they are made to work as prostitutes, so they are taking cabs, taxis, early morning, late at night, to-and-from clients. And then a single person who is controlling this group of women, usually a man, may go to a fast food restaurant at the end of the shift of work, and buy food for 10 women who have all been working all night long, and take that home to them. So those are the sorts of things that you piece together as you think about a typology.

Turner: I'm assuming you probably found that from a case that actually got solved, and you can take those patterns and apply them across other transactions or other accounts, or something like that.

Natasha: Yeah, so what you're always trying to do is identify not only an individual instance of crime, so, “Okay, this person looks suspicious to me,” but also patterns. So, “Okay, I've had ten of this type of thing. What are the similarities between these accounts that have made me suspicious of all of them?”.

And once you identify a certain number of accounts acting in the same way, then you may call it a typology. You'll probably build a transaction-monitoring rule specifically to look for that kind of thing.

Turner: So in that case, you've probably found some instance of human-trafficking, if you're the bank, do you usually relay that to the government entities and that's off your hands, and you watch it keep happening and wait for the government to intervene? How does that usually play out?

Natasha: Sometimes very like that. It can be quite demoralizing. I remember when I was at Monzo, we found some suspected human-trafficking and our onboarding flow was looking at, we used identity-verification providers to take a video, and you'd hold up the phone and say, “My name is Natasha and I want a Monzo account.” And it would help you onboard so that the bank could understand that you are who you say you are.

And we were seeing a lot of these videos with women in the same room, with the same table and tablecloth and they have bruises on them. So we could see that these women were probably being forced to carry out the identity-verification to open an account. And we submitted all of this information to the National Crime Agency, and then very often you hear nothing back.

And you as a bank decide on your own risk-appetite as to whether you will keep accounts open or close them. And banks have different views on this. It's totally down to their own risk-appetite. Then you have to make a decision of, do you continue to bank with these people? How many times do you become suspicious before you decide to exit them? And so on.

Turner: Wow. It's kind of demoralizing.

Natasha: It is. Yeah. I think one of the stats that I find the most interesting and the most demoralizing and depressing is 4 in every 1,000 people in the world is in modern slavery, which means that they are in forced labor or forced marriage. They've been forced to marry someone because somebody else made money from that, or they're being made to work probably in horrible conditions on a drug farm or something like that. Four in one thousand people. One thousand people is not that many. We all know more than that, far more than that, which is horrifying to think about.

Turner: That's like the entire population of London plus Birmingham or Newcastle. It’s a pretty big number when you really think about it… that's crazy.

So then when you're looking at some of these large-scale enterprises, is there usually a real business? Let's say, a very popular drug, they're smuggling it into the country, but is there some kind of manufacturing business that's attached to this? Or maybe it's an agriculture business or fishery or something, and they can hide these transactions with a real thing that just makes it even trickier? Is that why it's so hard to catch some of them?

Natasha: The Breaking Bad example of they're doing some legitimate stuff, and Ozark, where they've got all these businesses and they do run a bar, but some of the money is laundered. Certainly that happens a lot. And that's why Ozark I think was probably so popular, giving some real life examples of how it actually happens.

It's often the case - I mean, we don't know in a lot of cases as well, or I should say, I don't know, and there are probably a lot of government entities that do know - but yeah, that's often the case. Bars, strip clubs, any cash-intensive businesses, those are commonly used for laundering money through.

Turner: I listened to this really good podcast on the history of Las Vegas, and a decent amount of Las Vegas was funded and built by the mob because it was so cash-based. And they're like, “Hey, these are actually pretty good businesses, but this is the perfect setup to also hide other illegal activities that we’re obviously partaking in.” Throughout like the last century, that the mob did.

Natasha: I think it's just how prevalent it is. Have you ever had a cleaner and you've paid them cash?

Turner: Maybe.

Natasha: Have you ever gone to a carwash and it's one of the ones where the people do it themselves, not an automated one, and you've paid cash?

Turner: Possibly?

Natasha: Those are risky businesses where those people may not be paying tax. That's tax-evasion. That's financial crime. So even without realizing it and even as a good-standing citizen, and thinking that you're following all the rules, you probably have met people, or maybe even unknowingly partaken in what becomes financial crime, because it really does touch everything.

Turner: I'm going to have to edit that portion out about admitting to… I'm just kidding. We'll leave it in. I guess a lot of people have speculated with crypto, this was this whole new window or world for committing. Do you know what percentage of some of that stuff was illegal activity, or was it really just gambling and were actual business activities?

Natasha: I have found some stats to help with this, but they're certainly not from Cable or from me. So Chainalysis is really good at releasing information about this. Definitely the amount of illicit activity is increasing in crypto, but the numbers are still really, really, really small. So the share of all cryptocurrency activity that was associated with illicit activity has increased over the last number of years, but it's still at like 0.2%.

Turner: 0.2?

Natasha: 0.2, sorry, language barrier.

Turner: Is that how you say it in the UK?

Natasha: It is. we say nought, yeah. And midday means very specifically 12pm, noon. Midday just means noon.

Turner: Wow.

Natasha: Midday does not mean the period of like 10 til 4, just so you know, if you have any English friends.

Turner: We are learning about crime and we're also learning about English-language differences between the continents.

Natasha: It will help you, don't worry. We also consider ourselves to be English usually, not British. Anyway, I digress. 0.2%. Because so much was being moved through cryptocurrencies, that did correlate to $20 billion over the last year. So $22 billion of illicit use of cryptocurrency activity, but that's such a tiny percentage of the overall amount.

Turner: Who knows what that even means? Someone would make up an NFT and then it would trade for 20 million dollars. And that 20 million is just made up out of nowhere. Fascinating. The evidence from Chainalysis about 20 billion dollars of financial crime that was committed over the crypto rails, in 2022?

Natasha: 2022, yeah.

Turner: How pervasive is fraud and crime across the economy? We think it's about 4 percent of GDP? That's the number that you think is a fair number to state.

Natasha: That's the last number that I think anybody has that we can use. It's the last number that the UN came out with. So that's the number that everybody will quote to you. There's no way to measure how much it is other than self-reported fraud. Self-reported as in, you've been the victim of it, I suppose, not if you're carrying it out, “Hey, I did this thing.”

Turner: The IRS will be like, “Hey, if you committed fraud this year, make sure you admit the income on your taxes.” I don't know if you've seen that, but that is literally on the IRS website. It's like, “Make sure you report your crime financial gains.”

Natasha: I wonder how many people fill that in every year.

Turner: They probably catch some people. I bet they catch at least one person every year.

Natasha: Maybe.

Turner: Like, “I forgot about this money I stole.”

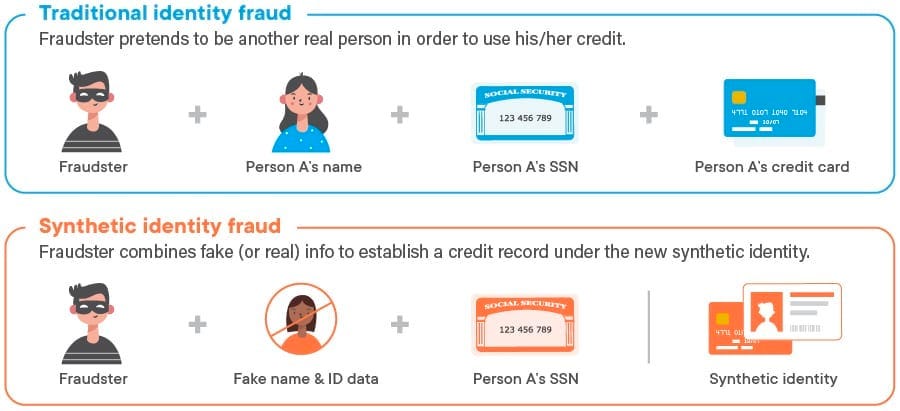

Natasha: But it's just endless. There are some reports that say synthetic ID fraud is the fastest growing type of fraud in the U.S. that cost six billion dollars last year.

Turner: What does that mean? Synthetic ID fraud?

Natasha: It's taking different bits of a real person and making up a new identity. So you may pass a credit-check with different elements of somebody else. And so it's really making up new identities using true pieces of other identity. You're persuaded to give somebody your ID, or there's a data-breach at a company and they get a lot of information, they could use all that information.

(Difference between traditional and synthetic ID fraud. Source.)

Turner: What do you think is the next frontier of fraud, if it makes sense, or what do you think is coming next? You talk about the synthetic IDs, is there a new way people are starting to commit, but then also pick up on, on the enforcement-side?

Natasha: AI is the obvious thing to talk about, but everybody is already talking about that. It's probably not anything new. People are being able to make deep-fakes or voice-spoofing. If you receive a voice-note from your mum, and she's like, “I am stuck at this supermarket and I can't pay my bill. Can you send, here's a link to pay my supermarket bill.” It's like $500 or, I don't know, something else that if it sounds like your mom, probably going to believe it. And that's now possible because of AI.

There are lots of scams that happen over phone or email. It's really easy to make it so that you call somebody or you text somebody and it says from HSBC, or from the IRS. The actual name that appears on your phone is really easy to spoof. So that's already really, really easy to do and happens a lot.

I received a text the other day from a legitimate-looking company saying that the payment hadn't gone through and could I please retry this link? And it's of course a scam. If you're buying a lot of stuff online, you may not know. You click it, you put in some details, and you've lost some money.

Turner: I've gotten that before with FedEx and AT&T payment, I think. It's probably every two weeks I'll get a text like, “Your FedEx wasn't delivered.” And I'll be like, “This is not right.”

Natasha: It's actually also really interesting how much easier that seems to be in America. I've just moved to the U.S. from England and I have had the same phone number for 15 years, maybe, in the UK, and I received maybe a handful of those texts or phone calls ever in the UK, and I have had my US phone number for five months, and I've already received multiple texts and calls. So there is some low control-bar happening in the U.S. with phone numbers that just make it so easy for people to find numbers and to try and scam you.

Turner: I have a hypothesis around this. Mine started when I signed up for a domain with GoDaddy. I'm putting them on blast. Did you happen to do that recently?

Natasha: No.

Turner: Okay. I swear to God they sold my information.

Natasha: I think probably lots of companies do it because there are more controls around that from Europe, which, obviously the UK is no longer part of.

You asked about new frontiers and fraud and things that might happen. The thing that I think is probably particularly worrying is actually for the first time in a really, really long time, people of our generation are earning less than their parents did, or are less able to buy homes or cars, or pay for education for their children.

And usually it was the case in most recent history that every generation had the chance to better their parents and to earn more. And with a whole generation of people really struggling to pay for stuff that would normally be considered a necessity, a place to live, a car to drive, especially in a country like America, which is so vast, you need a car.

There's a lot of people who just can't make ends meet and are dissatisfied, probably a bit pissed off with the government, and sitting at home wondering how on earth they're going to pay their bills this month. And if there are more easily-accessible scams, you can claim naivety, and you can make money really easily, why would you not become a payroll-provider for a nanny company?

Turner: I'm really interested then, learning all this stuff that you've learned, maybe we can talk about the Natasha life story. You worked at Monzo. How did that job come about?

Natasha: I was working in corporate finance. I had done a law degree, realized I didn't like law. I went into accounting. I became an accountant because if you don't like law, I guess, the most obvious thing is then to become an accountant or something.

Turner: They’re both really dry and boring.

Natasha: Exactly. So I went into that and I became an accountant and I worked in corporate finance for five years and also hated that. And then wanted to get into tech and didn't know what that was. And I was lucky to have a very good friend who was building a startup in London back in 2014, 2015, which was very early for that scene in London. We talked a lot about what tech was and how to get into it.

And I decided that the next interesting area to get into in tech that might become big at that time was FinTech, or at the time it was called challenger banking in the UK, and there were a handful of companies doing that, and Monzo was one of them. There were two startup fintechs that managed to get banking licenses really, really early on, Monzo and Starling, in the UK.

And so Monzo is one of the earliest fintechs in the UK. They have an actual banking license, they are a bank, they now have over 7 million customers. They've got the highest NPS of any of the banks in the UK, I think that's still true. It's a really, really great banking product, they offer savings, credit cards, all that kind of stuff now. And I joined when we were about 17 people and we had about a hundred customers. It was before we became a bank.

Turner: A hundred customers. Okay.

Natasha: We were not a bank, so they were what we called prepaid card customers. We were using Wirecard's banking license, which is amusing given how the Wirecard story ended up…

Turner: Yeah, okay.

Natasha: … in a fraud-related story as well, yeah. Nothing to do with Monzo, to be clear.

Turner: So then how did you get that job at Monzo? How did you know that Monzo was a thing and how'd you convince them to hire you, lawyer, accountant, corporate finance person?

Natasha: Yeah. So I had decided that fintech or challenger banking was the best place to go if I wanted to be in tech. And I knew a little bit about it with my background, and I did some Googling and found that there were, at the time, there were like four startups trying to become banks in the UK. There was, it was called Mondo at the time. That was the original name. Mondo, Starling, Atom, and Tandem. They were the four. I don't include Revolut in that list because at that point they were very much pitching themselves as just Forex. And I was wanting to work for a bank rather than a Forex company.

Turner: And then wasn't there one called M21 or N21 or something?

Natasha: N26.

Turner: N26. Were they not in the UK?

Natasha: There was a U.S. FinTech called M1. No, N26 is based in Germany.

Turner: Oh, Germany. Okay.

Natasha: They expanded to the UK for a while, I think they're no longer in the U. K., but they're in a few other European countries, yeah.

Turner: I need to get my European fintechs all sorted out apparently.

Natasha: Yeah, all squared away. The original fintechs.

Turner: Yeah, now I've got it though. Somebody quiz me after this episode, I'll get it right.

Natasha: So I found these four. I decided that Monzo were doing it the right way. I really liked the founder and CEO, Tom Blomfield's approach and the things he talked about. And I contacted them. I think there was a job online for an engineer and a marketing person. And then there was a, “If you're smart and you think you can help, email us and we'll chat.” And I contacted Tom and I was like, “I want to build a bank, and this is what I would do if I were to build a bank.”

And I had a very strange interview process, actually, because it was before they had an interview process. At that time, they may have only been ten or eleven people, because I delayed my start. I'll explain why in a second. So it was really small, and I went and met them in the pub, and then we went to a piano bar one day, and then I went and met them at the office, and then they asked me to organize an event to do my interview process, which I did, and then I got a job.

And I was originally just coming on board to be a business operations analyst, just to do anything that I could to help make the startup still live. There was someone else also doing that role. So I was coming in to work with her to do stuff to help Monzo succeed. And before I joined though, I went to San Francisco and I learned to code. I did a coding bootcamp, which was amazing. So that's why I then delayed my start at Monzo by about three months, to go and do that.

Turner: Did you feel like that was a necessary thing to get a job at a startup?

Natasha: No. I did not understand how if somebody wrote some numbers and letters into a computer here, somebody on the other side of the world could interact with it. I just did not understand how that would even work. And I just thought that if I was ever going to have kids, they would know this stuff, and I would not understand it at all.

So I was just interested in understanding how it worked. Turns out I loved it. And another path I could have taken was just to try and be an engineer forever because I loved it so much. It really goes very well with my black-and-white mentality and being able to solve problems really easily. So I really, really enjoyed it.

Turner: So were you able to apply some of it when you came back and started at Monzo?

Natasha: Not as an engineer. I tried for about a month and then I realized that my three months of coding in a different coding language did not help me be able to build a bank. It was like, “Yeah, we're building a payment processor.” I was like, “I think that might be above my skill-level.” So no, I didn't.

But I then, after about four months of being at Monzo, we had some fraud, and I was asked to deal with it. And I became the one-person financial crime team. And I think that financial crime, or financial crime-detection, is really the perfect combination of law, accounting, and coding. Because you're applying regulation, you're trying to understand it, you're looking at money-movements, the ins-and-outs of it, and then the solution is very often rules-based, working with engineers and building systems. So I think actually, it was the perfect combination of everything I had done, which was purely by chance. I wish that had some degree of me putting the blocks together, but it was just by chance.

Turner: So before we dive a little bit deeper into that, you said something I thought was really interesting. You said you thought Monzo had the best approach out of all the challenger banks. What do you think was right about their approach versus the market?

Natasha: It's a good question, and I think it's actually a really interesting debate. The whole Monzo, Starling, Revolut race that happened in England and in Europe is really fascinating. And I think there's a whole couple of hours we could talk about with them in mind, which we probably shouldn't get into in too much detail.

But at the time, Monzo and Starling were trying to get banking licenses. Atom was focusing on mortgages, so they were not trying to be a consumer bank. And Tandem, the founder had done some other stuff before and I think I was just more interested in Tom's approach to things and the way that he spoke and the way that he was.

So really, the two that it came down to were Monzo and Starling, and as it turns out, they had started off as one company and then split. And there's a lot that you can read about that online that I was not there for it. So I don't have firsthand information for you. So everything I would say is secondhand, but interesting backstory to Monzo and Starling.

I like Tom, I thought he was, Tom and Jonas, the CTO, I thought they were doing really, really smart things and approaching the whole bank from the ground up. They were not buying a payment processor. They were going to build it all, which I thought made a ton of sense, because the fundamental ways that you improve the customer experience is being able to control everything in that flow of money. And they were doing that rather than buying systems to help them do that.

Turner: That's incredibly hard though.

Natasha: Yeah, they did it all. It was amazing. I think that they had some of the best engineers I've ever met, in this small room. They're a handful of them who were absolutely brilliant. The whole Monzo, Starling, Revolut, Ultimate journey is a really interesting one. Monzo took a very community-focused approach. It was a great place to work. Almost everybody who worked there really loved it, and they were very thoughtful about things that they did. They got a banking license, and that meant that releasing products had to go through committees and processes and sometimes to discussion with the regulators.

And then on the other hand, of course, you've got Revolut, very much more of the move fast and break it mentality. The Silicon Valley mentality. People I think either love it or hate it, working there. And I certainly know people who love it, as well as people who didn't. And they did not get a banking license. And that meant that they could release products super, super, super fast with way less controls around it, way less of committees and process and regulatory involvement. And so there is no doubt that they released more products way more quickly than Monzo.

But then they have struggled to get a banking license. That's been a hot topic in the press this last year. The will-they, won't-they get a banking license, they keep saying they're really, really close to getting it. The regulators keep saying they don't have it, keeps going back and forth, who knows if they'll ever get it? What happens to that business if they can't get it? If they cannot become a bank, what happens to their 20, 30 million customers and that money? How insured is that? Will they be able to continue to exist?

And that's really interesting, especially if you start to think about the shifting regulatory landscape in the U.S., where the regulators are getting much more involved with the fintechs, who are the customer-facing product, who are not directly regulated. That is the situation with Revolut. And so without those controls in place, without all of the process that is needed if you're a regulated entity, what does that mean for Revolut longer term?

Turner: And do you think, at least from what you've seen from your data, do neo-banks or challenger banks, however we want to define them, this new financial services companies that are digital first, is there a higher rate of financial crime that passes through their gross-transaction-volume percentage or is it probably pretty similar or less than the incumbent banking system?

Natasha: There have been a lot of articles. There was one in America recently, last year I think, about how fraud rates at the fintechs was a lot higher than at traditional banks. At Monzo, we prided ourselves on our fraud rates being really, really low. So we measured it all and we had lower fraud rates than the industry averages by quite a significant amount. And we released blog posts explaining that. But generally, yes, I think there has been higher fraud as a general industry.

Turner: So then how long were you there? This was like four or five years, right?

Natasha: Yeah, four and a half years I was there. So I left Monzo at the end of April and my wife was expecting our first baby, and I knew I couldn't leave and not have a salary. So I spent about three or four months working at some good friends’ financial crime consultancy, it's called FinTrail, and I spent the majority of that time really writing the business plan, speaking to customers about Cable, and I did a little bit of consulting work for them, that FinTrail then helps precede, I should say, Cable, which yeah, was the sort of deal there.

Turner: Was there a moment when you were like, “This is the idea for Cable. I have to do this.”

Natasha: December 2019, I took that whole month off. I was super burned out. I was really, really stressed, and I had been wanting to take a break since about February of that year, but I had to hire a senior management team into the financial crime team.

I had been doing financial crime at that point for like four years and I was hiring people from Barclays and HSBC, who had been in the industry for 20 years to report in to me. The whole bank was very much shifting from startup to proper bank, which it had to do.

Turner: What was the size of Monzo and the valuation of the company at the time? This was like multiple billions, right?

Natasha: Yeah, yeah. When I left, we had four and a half million customers. The team was like 1,500 people and we were worth a couple of billion.

Turner: Then what is it at today? You said about 7 million customers?

Natasha: If not more. And the last valuation was four and a half billion.

Turner: Monzo was a real business. You were trying to hire people that had decades of financial crime experience to augment everything you were doing. You took this time off. What happened during that December?

Natasha: I spent a month wondering, “Do I want to go back?” I was so stressed, “What should I do instead?” I spoke to a lot of people and I went back in January thinking, “I'm going to see how it goes and I might look in the future.” And on day one I was like, blood pressure up here, heart palpitations, just super, super stressed. “Can't stay here, I need to get out.”

Turner: What was so stressful about it?

Natasha: I think I had just gotten to the point that I felt so invested in its success, but I was not a founder and I was not somebody, I was not a C-level employee either. And I couldn't control the direction of the company. And this is not to say that my ideas would have been better in any way. I think the management team have done very well to navigate the COVID situation and to get the business where it is today.

But I was feeling like I would make different decisions about some of the stuff that was happening and I found it really stressful to be running this team and be responsible for all of this stuff, but not being able to actually decide the direction in which my team was being sent to run. I think I wanted to work in a slightly different environment as well. Monzo was a really, really awesome place to work. And Katie, my co-founder at Cable, we took some of the stuff from Monzo into how we built Cable, but we also took some stuff and said, “Okay, we know that that was done at Monzo and we do not want to do that.”

There are always pros and cons to businesses, I'm sure for Cable as well. So I went back in January of 2020, decided I didn't want to stay and I spent a couple of months trying to work out whether I wanted to go work for somebody else, another startup, or whether I should actually just do my own thing.

To boil it right down to the basics, what my job was, we were in what's called the first line of defense of a bank. We were building financial crime controls to try to identify fraud and to identify suspicious behavior. We built the entire onboarding journey for the bank. The customer-facing experience, if I'm signing up for an account, I'm submitting information the bank is verifying.

Turner: So the financial crime detection team was actually doing the onboarding.

Natasha: There were product teams involved in, “How should we make this screen look?” But we were saying, “Okay, we need to request this information at this point in time. You cannot move forward until you get these results back,” and so on.

Turner: And that's because getting that information helps catch people early on in this journey of committing some kind of crime.

Natasha: And it's a regulatory requirement. So you have to know who your customers are. You have to gather certain information. You have to verify it. And then we also built transaction-monitoring in-house. We built a whole system to try to identify those suspicious activities. We built controls for account-takeover or for 3D secure, that verification flow, if you're buying something online and you get sent to your bank. We built all of that and we thought we were pretty good at stopping crime.

We found really interesting stuff. We were identifying - there were all these times where we would see this money come in and we would stop it. Our automated system would say, “Okay, I'm going to stop this 50K payment.” Because the system thought it was crime, and we would review it and we'd be like, “Yeah, this was fraud. The bank that this came from, I don't know, HSBC or Barclays, their customer was defrauded and this money belongs to that customer. We should send it back.” And we'd call or email the bank and we'd say, “We've got some of your customer's money. This is crime.” And the bank would be like, “No, no, no, it's fine. You can send that money on.” And we'd be like, “No, it's really crime. It's fraud. Do you want this money back?” And they'd be like, “No.”

And then three days later, we'd get a call being like, “That money, that was stolen. Please. Can you send it back?” It's like, “Well, yeah, we've got it for you. Thank goodness.” And that happened a lot. And we felt like we were pretty good at stopping crime. But we didn't know, because criminals never tell you, “Here's my annual report for how much money I laundered through you.” No one tells you that, right?

And there is another regulatory requirement that banks have to independently test if your controls are working. How effective are your Know-Your-Customer checks and your OFAC screening? How effective are your transaction-monitoring rules? Are you doing all the stuff that you're supposed to be doing? And how well are they working?

Turner: And those things are basically - Know-Your-Customer KYC is making sure it's a real person, real business entity, with commercial purposes. That's essentially what KYC is, right?

Natasha: Yeah, it's gathering certain bits of information and then verifying them to make sure that you know that the person you're speaking to is not only a real person, but the person that they're supposed to be.

Turner: So obviously I could steal your identity and bank as you. And you need to know that it's not actually Natasha, it's someone's pretending.

Natasha: Correct.

Turner: Okay.

Natasha: We bought all of that stuff. We had half of the team, in the team that I ran, were engineers and data scientists, and we spent millions on technology - buying tools, buying other checks, and so on. And there was this other team at Monzo whose job was to independently test our controls. By the time I left, the team that I ran was about 40 people. That other team was like three or four people. Now, I believe it's much bigger, but at that time it was like three or four people. There was no technology they could afford. And they had no engineers and data scientists. So they would manually review 10 accounts a month of our four and a half million, and come to me and say, “This is how well your controls are working.” Randomly pick ten accounts and then extrapolate out and say, “Okay, well this means that we're this good.”

Turner: That sample size, that seems way too small.

Natasha: And then we'd pay KPMG a hundred grand to manually review a hundred accounts of the four and a half million that we had. And that's how this regulatory requirement of effectiveness-testing was satisfied. It's still how it's done almost everywhere.

So the idea that we had was, “Well, firstly, that's crazy, and that should be automated.” So the idea was, “Can we automate the effectiveness-testing with the ultimate goal?” Taking this back to the first half of this conversation and everything we talked about - our mission at Cable is to reduce financial crime. Because if we can reduce financial crime, the ability to move all that money, then we think we can reduce all these crimes and all the impact on the humans.

If we can make banks more effective, if we can actually tell them how good they are at stopping crime, then we can, over time, make them more and more and more effective. And then we can reduce financial crime and reduce all these impacts on the people in the world who are being impacted by financial crime and some who don't even realize that they are being impacted yet.

Turner: If we can level-set, what exactly is the Cable product and how does it work today? I think I have an idea, but I don't think anyone listening, can you just get us all on the same page real quick?

Natasha: Yeah. So we have a few different products. The main product, the thing that we built that we were the first people to build, and we don't actually know if anyone else has done this yet, we've not come across anybody else doing this, is what we call financial-crime-assurance. We take in bank data, account-level data, transactional-level data, and we monitor it all of the time for any regulatory breaches, any control failures, or any indicators that controls might not be effective.

Turner: And is this the sampling or is this literally all 7 million accounts?

Natasha: It's all seven million accounts. So it is replacing tiny-sampling. We're doing it across 100 percent of that customer base. And instead of maybe finding an issue in a sample where the issue started occurring three months ago, we flag the issues in real time as they occur.

Turner: So then who's the end user of Cable, is it the compliance regulatory team at a bank?

Natasha: Yeah. And it's usually the compliance team, the financial crime team, sometimes. The interesting area that we're getting into is that the business team that wants to drive growth is often our foot in the door. Compliance teams always say no.

Turner: Yeah - no new business.

Natasha: Yeah, that's always the complaint from the business team, “Compliance wants to slow down. Compliance doesn't allow us to onboard more customers, release this product, move faster.” And so one of our taglines at Cable is we help compliance officers say yes. So that assurance piece is one of our products. We also have a few different products. I'll mention two others.

The first is a risk-assessment product. So it is a regulatory requirement for banks to do financial crime risk-assessments to understand what risks do they have? What controls do they have in place to mitigate that risk? And how effective are those controls? And so what is the ultimate or residual risk that they are carrying?

And they have to produce one of these risk-assessments at least annually, and that is supposed to drive business priorities. It's one of the things that the regulators check. Almost every bank in the world does this in a spreadsheet. And even if it's in a tool, then it is a static once a year, once every six months, static risk-assessment in a tool.

What we've done is we've integrated, and again, we think we're the first people to ever do this, we've integrated the risk-assessment with the automated-assurance tool. So if through monitoring all of the accounts that a bank has, if we find a regulatory-breach or a control-failure, we automatically update the effectiveness of the control and the risk-assessment, which automatically updates the residual risk or the overall risk that something has in the risk-assessment that the bank has. And so we’re changing a lot of these financial crime compliance processes from being once a year, really manual processes, to being always on, always updating processes.

Turner: And they're look-backs, right? It's like April of 2022, and you're doing your December ‘21 risk assessment or something?

Natasha: It's usually trying to be forward-looking. So, “Okay, it's nearly the end of 2023. I'm going to pull together my 2024 risk-assessment.” But what we're saying is, “We're going to give you a real-time updating always-on risk-assessment that is based on what's happening today.”

Turner: And what is a risk assessment? Is it like, “We estimate that this is how much of something is occurring.”

Natasha: So today, very, very finger-in-the-air. There is a risk that we have account-takeover. I think the risk without any controls in place is pretty high because we're a large bank. It's probably a five on a one-to-five scale. I'm going to put some controls in place to try and reduce the risk of account-takeover. I'm going to put in identity verification, I'm going to put in some IP-tracking, and I'm going to put in some 3DS. I don't know.

And I think those controls are 80% effective. So in my residual risk, the outcome-risk a one down from a five. But these are all finger-in-the-air. I'm going to choose a scale, one-to-five, one-to-three, high-to-low. I'm going to choose a way to measure my effectiveness, which again is based on tiny-sampling or finger-in-the-air. And then I'm going to come out with this end-risk. What we're saying is, “We're going to monitor all of your customers and tell you actually how effective these controls are.”

Turner: What's usually the result of implementing the product? Is some of the stuff worse than expected? Are they able to catch problems sooner? What usually happens?

Natasha: Catching problems sooner, catching problems they didn't know about, catching problems that are introduced through product releases or changes. That's what's often most surprising to teams, or specifically engineering teams.

So, there are countless examples of: engineering team says customer can't do Y before X happens. And therefore, the control is working and you don't need to test it. But, engineering team then goes and releases a new product or makes a code-change, and suddenly you can do Y before X, and that's now a problem. And nobody picks it up until dip-sampling. In your sample of 10 accounts, you happen to stumble across an account that this has happened on, which might take you a year. Whereas Cable will identify that as soon as the change is made.

Turner: So if I'm the compliance person that's manning the Cable dashboard throughout the day, I'll get a paying like 120K transaction. You click it to dive in and do some research on it. And it's an instant thing. And I can immediately solve some of this stuff.

Natasha: Yeah, so it's like, “Okay, we have now identified ten accounts that you've not received a valid name for, or the date of birth might be wrong, or they've not gone through this flow of controls that you set up, that we've configured for you.” We put the user IDs, and they can dive in and remediate those accounts right there.

Turner: So this happens instantly or next-day?

Natasha: However often the customers want us to be doing it. So we have an API. It can be done on an ongoing basis. We can also do data pools from data warehouses. We have an integration with Snowflake or BigQuery. So there's a few different ways that it could happen.

Turner: So then how did you get the very first customer? What was the product like when you convinced someone to pay for this?

Natasha: Well, the very first customer was a free proof-of-concept with a company called Tide in the UK, and they then did become our first paying customer. We had an idea, we knew what we wanted to do, and we persuaded them to give us their data so that we could prove it worked.

We took their data, we ran it through the system that we built, this really, really early product. We put some stuff in a webpage for them to look at, which was very manual for us to do, and really hacky, managed to find value for them in this data, managed to show them how effective their controls were. They're now on a new two-year contract. They've been using us for over a year already, we renewed them recently.

Turner: So then how much do people usually pay for something like this? Is it a couple thousand a month, a year, six digits? What are the contracts? You just said you signed a two-year contract. What do these usually look like?

Natasha: Well, most of our contracts are two or three years. So they're starting to look quite enterprise-y. We are currently pricing just like SaaS-based pricing, annual licenses, but we're moving to usage-based. We're launching transaction assurance. So we have been taking in the account-level data and monitoring for the regulatory breaches and control failures across account-level data. And we're going to start taking in this quarter-transactional-level data too. So we'll start introducing usage-based pricing, volume-based pricing for that.

Turner: Any time you catch an issue, that's what people are paying for essentially?

Natasha: People are paying for us to be monitoring their customer-base. So we're monitoring it all the time. And for compliance officers, no news is often good news. And so they are paying for the fact that we're monitoring it and providing peace of mind, even if there are no issues found.

Turner: Did you set up pre-seed in a seed round or what's the status of all the fundraising with Cable?

Natasha: Yeah, we've raised just over $16 million so far. We've done a pre-seed, a seed, and a Series A.

Turner: So how did you get the very first round done?

Natasha: At that time, my co-founder was still at Monzo. So it was me and a business plan. I still don't quite know how I got that raised. I knew some angel investors in London. One of them's Charlie Delingpole, who had founded ComplyAdvantage and MarketFinance before that. And he's done a lot of angel investing.

And another handful of angel investors who were prolific entrepreneurs in Europe, I got them to commit some money. And then they introduced me to their favorite seed, pre-seed VCs in London, and I had two term sheets and I went with LocalGlobe. They've been a really great partner. Remus there has been awesome to work with. They put the first check in, so that first round was just £675,000, so like $750,000. And that was back in September 2020, it closed. Just one month after my first daughter was born. That was just me and a business plan and then had to hire some people.

Turner: After you raised that pre-seed round, did you start adding some of the other products?

Natasha: No, not after then. So the pre-seed money we used to hire our initial team, for my co-founder to go full-time. And then for us to build out very, very early MVP and get the three, we did three proof-of-concepts, and we were turning them into full contracts.

And then we raised a seed round, which was led by CRV. And that one, that was four and a half million dollars. And that was back in August, 2021, I think that closed. So that was in 2021. And we used that money then to build out our team and actually build a lot more product.

Something that we learned that was interesting was, people don't like buying compliance products unless there's a lot of compliance products. Compliance officers are conservative people. And they're not going to put money towards something that necessarily looks and feels really, really early in a startup.

So we had to just build more stuff to be able to sell to these conservative people and to get budget. So that's what we did with the seed money. We built a lot. We started signing more customers. We started building some repeatable processes.

Turner: And speaking of CRV, I asked Caitlin, who I think is on your board at CRV?

Natasha: She is, yeah.

Turner: She said you had a very interesting approach to how you did the seed round, specifically with all the angels that you brought on. Can you talk about your process?

Natasha: Yeah. So the pre-seed round was, I think there were eight angel investors. They were all white men. And at the time I was like, “Awesome. People are giving me money. They're really experienced. Just take it.” And then we raised that money. And then I was thinking about the next raise and I was like, “Oh my gosh, my cap table is totally one-sided and not diverse at all.”

And so we very much wanted to approach the seed round and completely change the makeup of our cap table. Three, four months before we started really going to market to try and raise that seed round, I started talking to angel investors and trying to get introductions to angel investors that 1, were more diverse, but 2, had been operators in areas that I did not have experience in and that Katie did not have experience in.

We managed to completely diversify our cap table after that seed round. It was 52% female, way more diverse in ethnicity and race and sexuality as well. There's a blog post on our website that shows how that all fell out. But I was really happy with how that came about. But also, we brought on people who had founded companies and were experts in fundraising or go-to-market, and marketing, and so on. And they've all been really, really helpful to me.

Turner: And then did you have any thinking around minimum check size? I know some people, you'll see specifically in the fundraise, like, “Oh, minimum of 100K.” I found, at least what I've heard from, and me personally in my own fund, someone invests a thousand bucks with the highest ROI of any check. Did you find that's the case?

Natasha: Absolutely. My most valuable angel investors, I think some of them put $2K in, some of them put $5K in. It's not only you're cutting off valuable resource, because they are often the most useful, but also it's just really discriminatory. A lot of people don't have 25 or 100 grand to put in. And if we're talking or thinking about trying to lift everybody up and give equal opportunity, then you have to give opportunity to the people who don't have 100 grand but may one day have that money. So I definitely did not set a minimum check size and those smaller check angels have often been the most helpful.

Turner: The interesting feedback I got too when I was trying to get into venture and VC, people I called, “Just start angel investing, right? Just like $10K, $20K.” I'm like, “I got like two grand in my bank account total right now. That's a little tricky.” So no, I like that you're thinking about that.

So then after raising the seed round, you said you built out a lot of the product, prioritizing roadmap, things like that, it was basically figuring out what your customers wanted, what the compliance officers needed to convert and pay. It was a fully-stacked suite, a ton of stuff, didn't feel like a startup. That seems like a tricky thing to balance. How did you go from scrappy startup to a polished product so quickly? Was there a secret?

Natasha: So it's still definitely being polished. There's lots that we're doing. No secret, just a lot of hard work and trying to move really quickly. So we listen to what customers want. We built out the risk-assessment product actually, because some of the people that we were talking to said that they'd pay for it before we built it. So we were like, “Well, obviously build that.”

We've always had this really interesting way that we imagine integrating these things. If that's what people want next, we'll build that. That risk-assessment product actually drove a lot of our then-expansion into partner banks. So the banking as a service space, there has been a lot of noise by regulators recently because the regulated banks who are partnering with all the fintechs, they have to understand how effective the controls are of those fintechs, and it's really hard to do that today, especially by dip-sampling. It's just impossible to scale the team at the bank to dip-sample over 5, 10, 15 fintechs, and however many customers they have.

And so we built out some specific features and products for partner banks, banking as a service banks. We've built a way for them to onboard their fintech programs. There was a regulatory order against a bank called Blue Ridge where the regulators were telling off Blue Ridge for not understanding the risk-assessments for each of their fintech programs, but also how those risk-assessments fed into the bank's overall risk-assessment.

And so we built, again, we think we're the first people to do this, a risk-assessment tool for partner banks, whereby they can onboard their fintech programs, have their fintech programs complete these risk-assessments, and the risk-assessments roll up and change automatically the risk-assessment of the bank itself. So we've built a bunch of features specifically for banking as a service banks, so we're continuing to build out features for them and their fintech programs.

Turner: So pre-Cable, that portfolio, the fintechs’ portfolio, was possibly a black box that they quite have visibility into.

Natasha: Yeah, and then they were trying to do, maybe quarterly dip-sampling, requesting data dumps, very, very painful emails, spreadsheets, just a lot of back-and-forth, a lot of manual work with limited visibility.

Turner: So you basically gave them visibility, and then instead of dip-sampling, its entire portfolio, each customer-level.

Natasha: We sell to the partner banks and they are making their fintech programs integrate with us because then the bank has complete visibility into how their controls are working.

Turner: Obviously you raised a Series A, what was the process like raising a Series A then?

Natasha: I was very, very lucky because I got preempted. Well, the round closed in April, so I got preempted in about February, end of February ‘23. In this market, felt very, very fortunate, and to be preempted by two funds that I really wanted to work with and I had been getting to know for a long time.

We were thinking we would go to market in April to raise our A. And I was speaking to Stage 2 and to Jump Capital and both asked if they could preempt right at the end of February. And I said yes. Within two weeks, we had a signed term sheet and four weeks after that, we had closed the deal and money was in the bank. Yeah, Stage 2 and Jump Capital co-led the round, and they've been just amazing partners, helping in any which way that they can. Really, really happy with them.

Turner: So what does the process look like of getting preempted for a round? People who don't know what that means, what does that mean and how does that happen?

Natasha: It means you are dating VCs and trying to lead them on without telling them that you're leading them on. It's the weirdest thing ever, and I definitely am not an expert in fundraising, but you're talking to all these VCs and the ones you like, you try and drop little crumbs that actually you're going to try and start fundraising soon. And are they interested? Do they want to take a look beforehand? Do they want the opportunity to maybe come in and lead the rounds without you having to go to market? Because you don't want to go to market. You don't want to run a month-long process trying to speak to 50 firms, because that's exhausting and time-consuming and takes you away from building the business.

So I seemingly successfully dropped some crumbs for both Stage 2 and Jump to pick up on and then they both asked if they could preempt. They just said, “Can we have a chance at preempting this?” And I said yes, asked them what information they needed.

We had pulled together a small data room, they reviewed that, they provided some term sheets, we had a couple of calls with their partners. We signed the term sheet after a day or two of negotiation about some of those terms. I was very, very clear that if they were going to preempt, it had to get done within four weeks.

Turner: Is there anything you would change about how you've built Cable so far? Any mistakes?

Natasha: Loads and loads and loads of mistakes. I don't know if there's anything I would change fundamentally now. I think the thing that is hardest to do, and it's still hard and I wish I had been told this and had it drummed into me before, was just to try to enjoy it. Being a founder of a tech startup is like being punched in the face every single day over and over again, and then having to go on calls and smile all the time.

It's so painful and it's so hard. I wish that people had told me before just to try to enjoy all the little bits. Because I wouldn't want to do anything else. I do love it, and even though it's painful and feels like I'm being hit in the face a lot, it is still probably the best thing, for me, that I could be doing.

Turner: Why is it so good if it's just painful and you're getting punched in the face? What do you like about it?

Natasha: I like being able to work on something that I actually think will change the world in a positive way. I like building a company that I would like to work in, trying to give people a place to work that I think they truly like to work at. And I like to try to prove people wrong. I like to try to prove that you can build a company not in the move fast and break things kind of way.

We treat people very differently. We have our operating system. We have quite a unique culture. And I think that trying to prove that you can do this with that kind of culture and mindset is also something that I'm really trying to do.

Turner: Do you have a founder, CEO, company, any of the three, that you really look up to that you've gotten a lot of inspiration from?

Natasha: There's no one, I think there's a handful of people. There are two of my angel investors who are both founders who stand out. One is Laura Spiekerman from Alloy. Alloy is another reg-tech company. They built identity verification and onboarding flows, and they also do transaction-monitoring now.

But she is an angel investor and she also has a young kid and will always reply to my emails almost immediately, endless introductions, help, advice, tips, conversations, always willing to chat with me. And I don't know how she does that, and run a company, and have a kid, and everybody who I've spoken to who works at Alloy absolutely loves it.

And she's one of three founders, they are doing great stuff there and I really admire how she's able to manage everything in her life. And another one is another angel investor of mine who has been running a startup and they've just decided to wind it down.

But the reason I really admire her is because it's very easy as a founder to pin your whole identity to the company that you're trying to build, and think of the extraordinary failure that would happen if it all falls apart and you can't raise money. Actually, it's just a company, and I have a family, and I have kids, and those things are incredibly important to me. And if Cable doesn't work, everyone will be okay.

And it's really hard to forget that. And this angel investor of mine, she is having to wind down her company and, all the conversations we've had about that, she's been so positive about it, and she's been so passionate about what she's been doing, but so able to separate out what is just a company from the rest of her life. And I think that is so important to do as you're trying to build a company and do this crazy thing that we've all decided to do for some reason.

Turner: Do you have a favorite interview question at Cable that you like to ask?

Natasha: I do, I'll tell you the question I ask every single person that joins Cable, but I'm not going to tell you what I look for because then everyone will know how to get a job at Cable. The question that I ask everybody is to tell me their story. And I say, “Don't just tell me your work story. I'm not just interested in your resume. Just tell me your whole story.” That's the question I ask everybody.

Turner: And you do not want to follow up on that.

Natasha: I do not. You'll have to apply for a job at Cable to hear why.

Turner: All right. What's the website again? Cable.tech?

Natasha: That's right.

Turner: Okay, cool. Well, we'll throw a link in the show notes. But this has been awesome. Thanks for coming on.

Natasha: This was awesome. Thank you so much for having me.

Stream the full episode on Apple, Spotify, or YouTube.

Find transcripts of all other episodes here.