Pinduoduo and Vertically Integrated Social Commerce

How the son of factory workers grew Pinduoduo from Zero to $100 billion in five years

In 2015, Colin Huang founded his third company, Pinduoduo (PDD). By June of 2020, it had become China’s second largest ecommerce company and was valued at over $100 billion in the public markets. How did a company that helped farmers sell fruit on the internet rise so fast in a market dominated by Alibaba and JD?

Pinduoduo, meaning “together, more savings, more fun”, eliminated layers of middlemen and flipped the retailing model from being supply-driven to demand-driven. The team used a mobile-first approach that gave it a fundamentally different product DNA than incumbents. It used fruit as a wedge to combine consumption with entertainment and created a vertically integrated gaming company. It took advantage of down payments from suppliers and used stretched payment terms to create float out of customer transactions. It used that float to fund customer acquisition, and then leveraged clever growth tricks on an emerging distribution channel (WeChat) to acquire hundreds of millions of overlooked customers for practically free.

Humble Beginnings

Colin grew up in Hangzhou, the home of Alibaba located in the Eastern Chinese province of Zhejiang. His father never finished middle school and worked in a factory with his mother. Colin excelled in math. At 12 he was invited to the Hangzhou Foreign Language School, attended by the children of the cities’ elites. He credits this to changing the trajectory of his life. He was among the top students at the school and received a scholarship to study Computer Science at Zhejiang University, one of China’s oldest and most prestigious schools.

He joined the Melton Foundation his first year and secured an internship at Microsoft China making $900 per month - more than his parents combined annual salaries. He then transferred to Microsoft’s US HQ, making over $6,000 per month.

In college, Colin met NetEase (gaming) founder William Ding after helping him with a coding question in an online forum. This serendipitous meeting changed Colin’s life. William introduced him to many other Chinese tech luminaries like Tencent (WeChat) founder Pony Ma, and SF Express (logistics) founder Wang Wei.

Colin then moved to the US in 2002 to pursue a Masters in Computer Science from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. By graduation in 2004 he had a full-time offer from Microsoft, and an impressed professor wrote letters of recommendations to the large US tech giants of the time (Oracle, Microsoft, IBM).

The summer before moving to the US to start at Wisconsin, William at NetEase had also introduced Colin to Duan Yongping, fellow Zhejiang University alum and founder of BBK Electronics. The two grew very close. Colin considers him a close friend, mentor, and he even helped Duan with his investing. Duan recommended he move to San Francisco to work at a promising young startup. Colin then turned down all of his other offers to join a pre-IPO Google.

Colin joined Google as a software engineer working on early ecommerce-related search algorithms. He quickly became a Product Manager. In 2006, Duan won the annual charity auction for lunch with Warren Buffett with a $620k bid. Colin joined alongside Duan’s wife and five other friends. It's said that this meeting with Buffett greatly influenced Colin’s crafting of the Pinduoduo business model. This included the power of simplicity, utilizing float, and redistributing wealth (as Buffett has famously pledged to donate 99% of his wealth after death).

Colin returned to China shortly after to work on a secret team launching Google China. He reportedly grew tired of constantly flying back and forth to the US pitching Google founders Larry and Sergey on trivial matters. The last straw was a trip to get in-person approval of a change in the color and size of Chinese characters shown in the search results. He left many of his unvested options behind and Google eventually shut down the division. Colin then followed many of his mentors into a journey of entrepreneurship.

The Birth of a Serial Entrepreneur

In 2007 Colin founded his first startup, Ouku.com, an ecommerce site selling mobile phones and other consumer electronics. His mentor Duan’s company was a large player in the Chinese electronics supply chain. Duan was an angel investor and likely helped in the early days. Colin built up Oaku to “several hundred millions of yuan” in revenue (~$20-40 million USD), but he stepped down and sold the company in 2010 after realizing JD’s scale would always grant it better terms from suppliers and he could never beat them.

Almost immediately, he brought members of the team to build his second company: Xunmeng. It was a gaming studio that built role playing games on Tencent’s WeChat. Some ex-Oaku and future Pinduoduo employees launched Leqi, which helped companies market their services on other ecommerce sites (like Alibaba’s Taobao and JD). Both companies took off. Then Colin got sick.

He had an acute form of Otitis media, which causes severe inflammation and pain behind the eardrum. This typically causes a loss of appetite and occasional fever, and Colin specifically struggled sleeping. He stopped going into the office, and briefly retired in 2013 at 33 years old. He spent over a year at home. He considered moving to the US to open a hedge fund. He also thought about starting a hospital after going through the painful process of treating his ear infection.

Over the next two years, Colin came up with the idea for what became Pinduoduo by observing China’s two largest internet giants: Alibaba (ecommerce) and Tencent (social, games). He’s quoted as saying "these two companies don't really understand how the other makes money." Both are massive, successful companies, however neither had figured out how to penetrate the others business.

Pinduoduo fell directly in the center of the two; social gamified ecommerce. It helped manufacturers cut out middlemen by selling discounted items directly to low income consumers, and monetized largely with advertising. It fell within the intersection of unique insights Colin gained growing up poor and every previous business he, his mentors, and his team had worked on.

Pinhaohuo: Selling Fruit in WeChat Group Chats

Pinduoduo was initially founded in early 2015 as yqphh.com, or Pinhaohuo (PHH, “piece together good goods”). PHH’s initial business model consisted of buying fruit in bulk from farmers and then selling it directly to consumers. China’s fresh fruit market was growing fast in 2015, but less than 3% was sold online. Colin raised an angel round from his mentors, and once again brought over the team from his prior companies. Many were lifelong friends, including current members of PDD’s management team like Sun Qin, Lei Chen (first CTO, now CEO), Zhenwei Zheng, and Junyun Xiao.

Pinhaohuo’s business grew entirely through group chats on Tencent’s popular WeChat (often called the Facebook of China). To start, they bought boxes of fruit from a local Hangzhou fruit market and separated them into smaller boxes. On April 10th of 2015, they spent a few hundred USD to run one ad on an official Hangzhou WeChat Account (similar to a Facebook Page) that showed up in users’ feeds. They had more than a thousand employees, relatives, and friends of the company share the post. By May 1st, they’d fulfilled a total of 5k orders. Daily order volume surpassed 10k soon after. They paid an average of $0.30 cents for each of these earliest users.

Pinhaohuo also relied heavily on WeChat Pay, WeChat’s in-app digital wallet that had launched in 2013. Most users carried a balance due to the popular Red Envelope feature, in which users sent small monetary gifts to family and friends during the holidays. Routing all payments through WeChat Pay provided extremely low payment fees, low friction for order placing, and PHH’s low order sizes enticed early customers to pay with their outstanding balances. Most importantly, Pinduoduo’s primary competitor today, Alibaba, had also banned its sellers from using both WeChat and WeChat Pay. Its biggest incumbent competitor was un-incentivized to react to this newfound distribution channel.

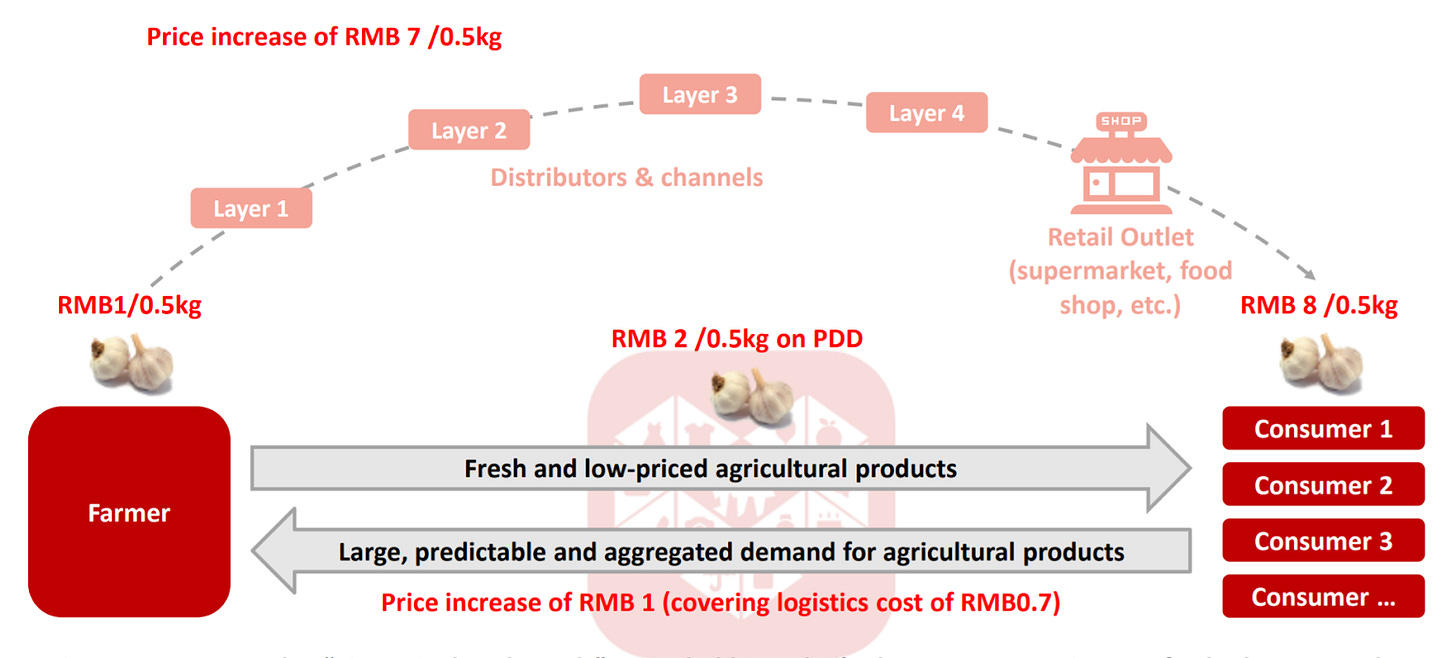

Over 100 employees were directly responsible for sourcing, inspecting, and purchasing fruit directly from local farms. Initially, this model worked in Pinhaohuo’s favor. Fruit has a short shelf-life and this model reduced the number of supply chain middle men. Wholesalers, logistics companies, fruit markets, and supermarkets taking a cut to support unloading, re-loading, and high fixed overhead costs were all removed. Farmers could charge higher prices while also cutting prices for consumers by 80%.

Logistics infrastructure that was built over the prior decade to support Alibaba and JD’s operations made it possible for the company to grow so efficiently, so fast. As described later, many purchases were entertainment-driven with low intent, which allowed for slower, cheaper shipping. They partnered with SF Express for deliveries, which was founded by one of Colin’s mentors (and an angel investor in the company), Wang Wei.

By September of 2015, Pinhaohuo had became China’s #1 free app and was receiving over 100k orders per day. Then came a pinnacle moment in 2015 when it sold its first batch of Lychee fruits (below). Its single fulfillment center, built to handle 70k orders per day, broke down when demand suddenly spiked to 200k. The front-end of the business wasn’t well-connected to the back-end. The order printer jammed up and deliveries bottlenecked at the warehouse as SF Express wasn’t equipped to handle the demand. Meanwhile, orders kept rolling in. Most of the inventory went rotten and the team missed a majority of its deliveries that week. Daily order volume quickly dropped 80% to 20k and customer retention the following month fell to 25%.

Colin held an emergency lunch meeting in the warehouse. He instructed the team to inform customers their orders would be fulfilled. When many were delivered rotten, customers were refunded. They hired 100 new operations employees and opened six new warehouses. Finally, Colin beefed up the executive team and everyone began to re-architect the entire supply chain.

Pinhaohuo quickly automated the warehouses to intake, sort, package, and distribute inventory onto trucks to be shipped out. Within a month, most fruit spent only a few hours in any of PHH’s six fulfillment centers. The time from farm-to-table was often no more than two or three days. They also productized the supplier sourcing process. This made the business extremely capital efficient and allowed PHH to hit escape velocity. The business ramped to over 300k fruit orders per day, and 600k soon after. In only a few months, they had surpassed the fruit businesses of both JD and Alibaba.

By the end of 2015, 10 million registered users were placing 1 million orders per day. Customer retention was 77%. Half the orders were still coming directly from WeChat. This all exceeded the local shipping capacity of SF Express and the team had to find more courier partners (some owned by JD and Aibaba) and automate their logistics business. This transformation proved crucial as many upstart competitors quickly entered and failed with Pinhaohuo’s initial model.

Pinduoduo and the Team Purchase Phenomenon

In 2016, Pinhaohuo merged with another company Colin had built, a game-like ecommerce platform called Pinduoduo. This combined PHH’s logistics expertise with PDD’s intimate understanding of the end consumer - which had roughly 70 million users playing 30 different social-based mobile games. By Q1 of 2017, the combined entity had completely wound down its operationally intensive direct sales model in lieu of an asset light marketplace. PDD took a 0.6% cut of all sales, or enough to cover payment processing costs. The majority of its revenue would eventually be generated from in-app ads purchased by merchants, as described later.

Pinduoduo was founded in the second half of 2015, around the time many of China’s first wave of group buying startups failed. Most launched in the early 2010’s to help brands unload excess inventory. Many were location-based services that deteriorated in quality with scale and single-player experiences that didn’t influence others. Popular items included discounts on consumer goods, meals at high-end restaurants, swimming lessons, yoga classes, and photography sessions. Brands were promised the discounts would bring new customers, but in reality no affinity was built towards any of these group buying products or their merchants: all consumers cared about was cheap prices. Of what were initially thousands of players, only a few were still in the market by the time PDD launched in 2015.

The largest was Meituan-Dianping. The company formed in September of 2015 when first-place Meituan (“Groupon of China”) and third-place Dianping (“Yelp of China”) merged, giving them an estimated 80% market share and near total control of what was an early and battered group buying market. Today, Meituan-Dianping’s main business consists of food delivery. It's begun layering on a very high gross margin (89%!) in-store, hotel, and travel business - indicating where Meituan’s strategic focus was in the years following the merger.

Another survivor was Juhuasuan (“extremely cheap”), which was the second player and incubated by Alibaba. It focused on connecting Chinese manufacturers with overseas customers and eventually found success as a part of Alibaba’s Tmall focused on high-end products. Vipshop was founded in 2008 as a site for in-season discount and off-season overstock clearance, and used special offers to grow into what is now a public company valued at $15 billion. When JD eventually entered the flash sale market, it tried to differentiate from Taobao by claiming to never sell fake or low-quality products.

This all left an opportunity for Pinduoduo in what looked like the unattractive, low-end of the market. The general consensus among experts was that China was going through a consumption upgrade. Consumers appeared to be moving from cheap goods to quality and overseas imports. The combined Pinduoduo and Pinhaohuo teams began quickly experimenting with new products, including meat and seafood. One of their biggest experiments was team buying.

Pinduoduo’s model was simple: buy everyday items and receive discounts of up to 90% by completing in-app actions or inviting friends to buy them as well. Prices were set by suppliers, and a user's very first purchase was almost always subsidized at a discount by PDD. Subsequent purchases could be made at the full-price, or discounted with a team or through in-app rewards. Users could join existing teams in the app, but prices were even lower if users started their own team. Early products were so cheap that there was very low friction to buy. The K-factor, or the average people a new user invites, was never less than 1. Any money spent to acquire one customer was ultimately acquiring multiple customers. As PDD grew, invites became less prominent. Purchases can now be batched together automatically (almost instantly), making every purchase a team purchase (though at slightly higher prices).

Where others failed with asynchronous purchases of “nice to have” high-end products, Pinduoduo created a synchronous mobile shopping experience equivalent to going to the mall with friends. Cheap essentials like toilet paper created loyal customers that invited their friends, worked together, and came back again and again. Failed competitors mostly had their own apps or websites; PDD was built entirely on top of WeChat. This loose network of friends allowed it to weave purchases made by friends as recommendations throughout the app - including “someone just bought this item” pop-ups that overlay products as users browse. While most ecommerce listings had reviews, few built-in these trustworthy word of mouth-like referrals from friends.

Socialized team buying also gave a psychologically different pricing structure than a product like Groupon. Instead of a listed price, Pinduoduo’s team buying approach meant everything was negotiable and most items could be earned for practically free with enough work. All team buys required an upfront payment that was refunded if the minimum team size was not met within 24 hours. This reduced the friction of initially committing to a purchase, while subconsciously committing buyers to work together to reach the target.

Team buying also flipped the traditional retailing model from being supply driven (“how do we sell what we’ve produced?”) to demand driven (“how much should we produce?”). This is a fascinating aspect of the business that I’ll touch on further, and it was only possible due to Pinduoduo’s mobile-first DNA.

Mobile-First Ecommerce

It's easy to claim team buying as the primary driver of Pinduoduo’s rapid growth. In reality, it was one of many subtle UI and business model changes that PDD used to become China’s second largest ecommerce company.

The biggest difference between Pinduoduo and incumbents was that the product was designed for mobile (web preview here). Instead of manually searching for products like on Amazon or Google, products were sourced to users in a feed similar to Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, or TikTok. In the early days, the app often had no more than 20 SKU’s at any one time. This allowed it to focus on a few core products while incumbents worried about customizing a long-tail of listings. It could then customize those products for consumers (as discussed later) after it hit scale, greatly reducing costs. It was positioned like a digital Costco while incumbents operated more like Walmart.

Pinduoduo (left) vs Alibaba’s Taobao (right)

Without an endless stream of search results, PDD’s users had a constrained choice. It also gave more accurate data on user behavior and interests that fed back into its algorithm to target users later. This set the stage for what eventually became a very lucrative advertising business very similar to the Facebook news feed. Being mobile-first allowed it to build a customer acquisition engine centered on messaging and social media, not email or SEO. It took desktop-first competitors years to react.

Like a traditional social company, Pinduoduo started predicting what users might buy. However unlike a social product that weaves ads into an unrelated experience, and ecommerce where there must be a related search prompt, PDD’s core product was designed around spurring purchases as part of the browsing experience. And its algorithm could push deals, not specific items. It became a virtual mall.

Pinduoduo’s product allowed new suppliers to quickly reach customers. Competitors’ interfaces were search-driven, required heavy investment in SEO, and often centered on multiple product displays. PDD’s feed-based interface placed more exposure on single products. This gave it full control over distribution to influence consumer purchase decisions in ways most favorable to PDD and its suppliers’. This was similar to how TikTok helped new creators quickly build social capital and earn fans:

TikTok could deliberately control the allocation of social capital to its most talented creators, both new or old, as new users poured into the app. Alex Zhu, Musical.ly founder and now Head of Product at TikTok, likens the process to creating a new country and giving a greenfield of opportunities to a new class of creators. Hyper fast user onboarding and no friend graph let it use the entirety of time spent in-app allocating social capital. Source

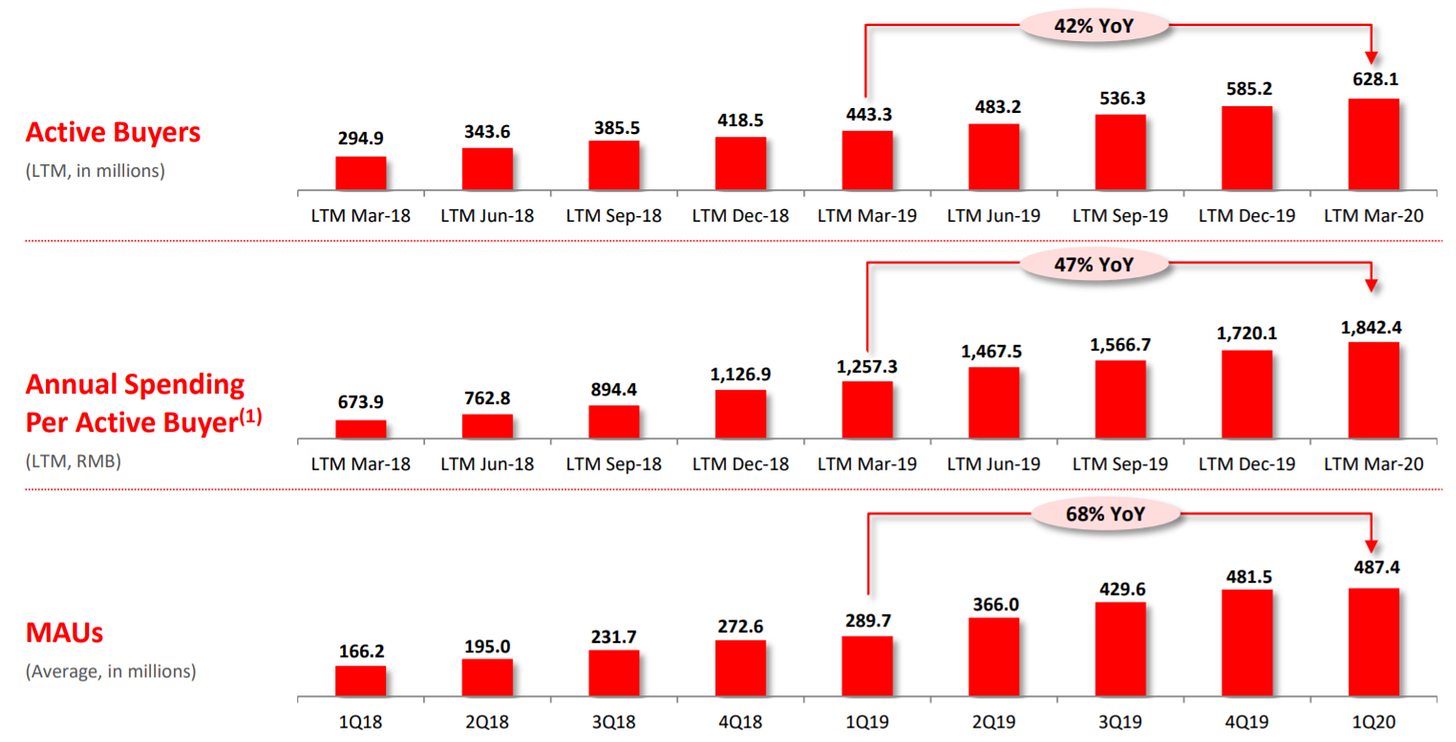

By February of 2016, Pinduoduo’s monthly Gross Merchandise Volume (GMV) exceeded ~$15 million USD. They raised a stealth Series A round from IDG and Lightspeed China in March, and a $110 million Series B from Baoyan Partners, New Horizon Capital, and Tencent (among others) in July. Shortly after, they surpassed 100 million Annual Active Buyers.

Tencent's involvement proved critical, as it allowed them to further invest in WeChat as a distribution channel. They could analyze the flow of social information and apply those insights to product recommendations, pricing, shipping optimization, and the product roadmap (like the clothing store below). Alibaba had also considered investing but moved too slow, allowing Tencent to start accumulating what became a 18% ownership stake at the time of IPO.

WeChat then launched its now popular Mini Programs in 2017. This allowed developers to build pared down apps (often less than 1 MB) that lived inside of WeChat. Many developers experimented with apps that complemented their existing products, but for PDD it offered a more sophisticated extension of the native distribution channel it built on top of WeChat.

By Q1 of 2017, Pinduoduo’s Annual Active Buyers had doubled again to 200 million. It then raised raised a $214 million Series C in February of 2017. GMV continued doubling every quarter and passed RMB100 billion, or ~$14.7 billion by the end of 2017, less than three years after it was founded. This was a historic milestone that took Taobao, VIP, and JD over five, eight, and ten years respectively to reach.

Pinduoduo continued growing at an incredible pace, primarily over WeChat. By July of 2017, it had served over 300 million users. In Q1 of 2018, it had over 230 million WeChat Mini MAU’s (Monthly Active Users). This represented 57% of all 400 million active Mini Program users, and more than the 166 million MAU’s that used PDD’s own app.

In April of 2018, Pinduoduo raised $3 billion at a $15 billion valuation. Tencent invested over $1.4 billion which further cemented PDD’s role as a favored member of the WeChat ecosystem. By the end of the year, over 1 million merchants were selling on its platform. 11.1 billion orders were booked in 2018, up 158% from 2017 and an estimated half of all incremental Chinese ecommerce orders added that year. Its most popular item? Tissue paper.

Fruit and agriculture remained a core pillar to Pinduoduo’s business as it retained customers and offered a launchpad for other product lines. Agricultural GMV surpassed RMB65 billion (14% of its total GMV) in 2018, making it China’s largest agricultural ecommerce platform. The agriculture business grew 114% in 2019 to reach RMB139.4 billion, with over 12 million direct and indirect agriculture suppliers reaching 240 million buyers (most of the active user base). In Q1 of 2020, orders of apples, cherries, kiwis, oranges, and strawberries all increased over 120% year-over-year. Rice, wheat, cooking oil, meat, dairy, and vegetables averaged a 140% increase.

While some of Pinduoduo’s incredible growth could be attributed to WeChat, one of the biggest shifts in Chinese consumer behavior has been from the “search, pay, and leave” model of traditional ecommerce to social commerce. That wasn’t just WeChat. Much of PDD’s recent success has been due to its game-like mechanics.

Half Ecommerce, Half Gaming Company

When Pinduoduo submitted its filings to go public in 2018, many were surprised it described itself as “Costco meets Disneyland”. It’s a strange comparison; and perhaps “Dollar Tree meets Candy Crush” or “a digital TJ Maxx” are more appropriate as the product stands today.

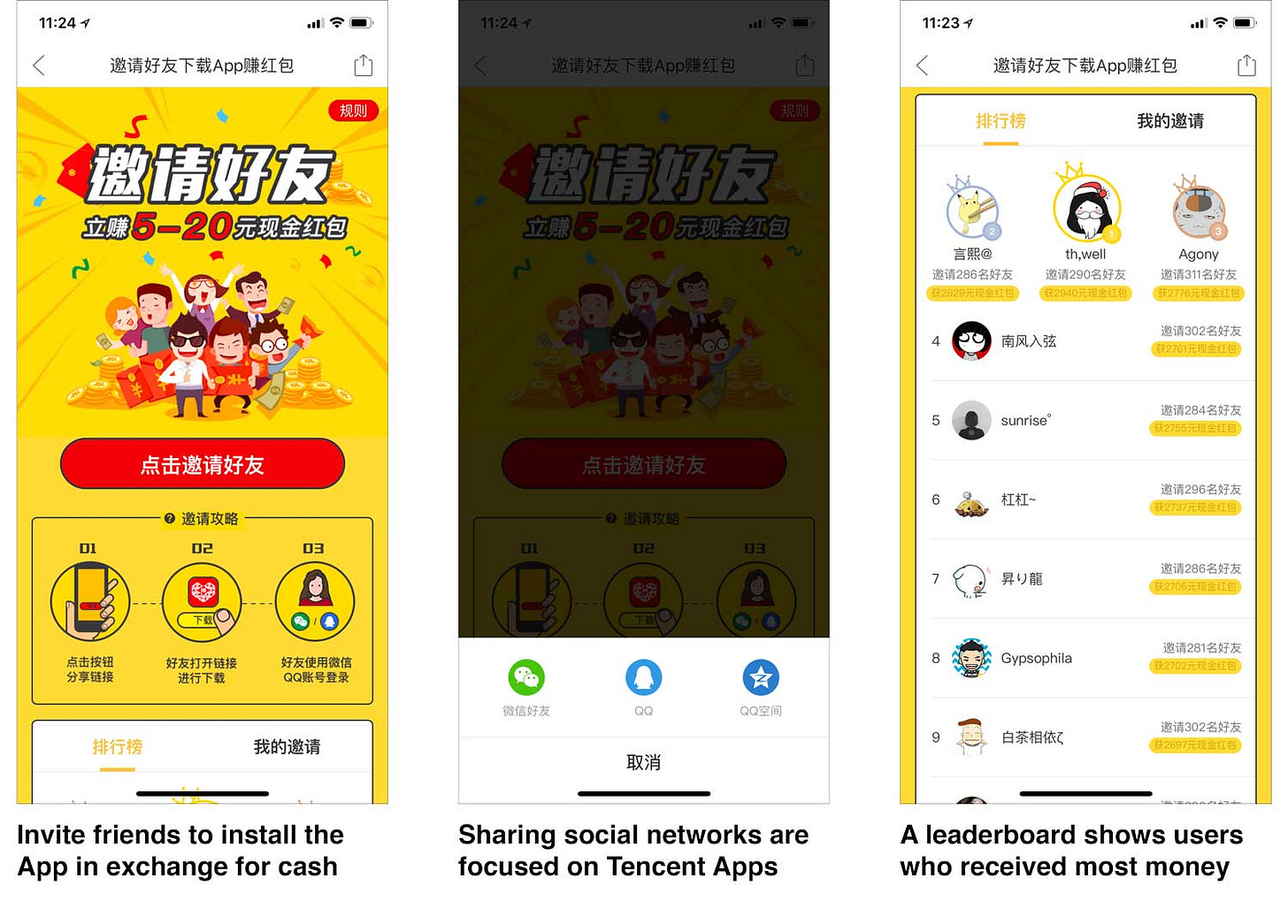

WeChat offered a tremendous arbitrage opportunity to initially acquire customers. In the midst of its meteoric rise, Pinduoduo was acquiring new customers for as low as $2 each, roughly 20x cheaper than the $40 paid by JD and Taobao. Over time, competitors figured out how to use WeChat for distribution, and PDD needed new levers to grow the business.

Citizens in China’s lower-tier cities where Pinduoduo amassed its initial user base have a lot of free time. Lots of that time is spent playing mobile games, and many of WeChat’s most popular early Mini Programs were games. It explains why the initial PDD concept took off so fast - it was really just a game.

The deals on Pinduoduo changed every day. The app had colorful photos and discounts were hidden everywhere. There was a wheel to spin for daily coupons, discounts for sharing invite links with friends, free products in exchange for reviews, and rewards for daily check-ins similar to Snapchat’s streaks. Some discounts lasted as short as two hours. This prompted quick participation and impulse buys. There was even a leaderboard showing who had saved the most money. One-tap payments and saved info after the first purchase made this entire process frictionless.

In May of 2018, Pinduoduo launched Duo Duo Orchard. It was a game to grow virtual trees inside the app. The more purchases, actions with friends, and time spent in-app, the faster the trees grew. When the trees were fully grown, the player was shipped a box of fruit. It was a virtual stamp card. One month after launch, 2 million trees were being planted per day. The game had 11 million DAU’s by June of 2019 and 60 million by December of 2019.

Unlike many social or gaming products that sell ads alongside non-related content, Pinduoduo’s entire experience is part of the monetization model. Every interaction builds up to a purchasing event. Many of the ads mobile games are monetized with eventually spurs some form of commerce. PDD built commerce directly into its games to capture more of the value chain. And much of that value went to its suppliers.

Consumer to Manufacturer: Eliminating Layers of Middlemen

Before the internet, most of manufacturing and retailing was “how do we sell what we’ve produced?” Even today, despite having direct relationships with consumers, many brands still order inventory from their suppliers up front before any sales are made.

In Pinduoduo’s early days, it helped farmers in small villages sell fruit directly to their neighbors over the community’s newly purchased smartphones. Combining fruit orders at the front-end helped PDD predict volume. It could guarantee sales upfront and reduce risk for suppliers; similar to government subsidies that support much of the world’s agriculture production. As consumers cultivated rewards in virtual games, it built in even more predictability. Farmers could optimize their harvests (for product quality, not shipment length), had more predictable income streams, and consumers paid lower prices for fresher fruit than they could buy in-person because so many layers of inefficiencies were removed.

As it amassed users, Pinduoduo began predicting, and then influencing consumer demand elsewhere. Its team buying model flipped the retailing model from supply-driven to demand-driven. It would be as if Facebook went a step further than partnering with direct to consumer brands dropshipping from overseas, and instead created a Shopify-like tool for those brands’ suppliers. In some cases, these were similar to a Pinduoduo private label. In others, manufacturers were building a consumer-facing brand for the first time. As Colin wrote in a now-deleted blog post: it eliminated economies of scale advantages, made small scale customized services viable, and allowed both small manufacturers and retailers to compete against larger competitors.

Taking learnings from Google and adopting the model used by Taobao (and pioneered by Pinduoduo investor and ex-Taobao CEO Sun Tongyu), Pinduoduo turned this into a marketplace. They called this “Consumer to Manufacturer”, or C2M. There was high fragmentation in the original supply of local farmers and the model scaled very fast. It guaranteed demand to suppliers, who would in-turn pay for that demand. Suppliers could eventually bid on in-app feed placement, banners, links, logos, and keywords in search results. They could control prices, group sizes, and how many orders they would ultimately fulfill. This allowed them to precisely predict their volume and input costs months ahead of time. It allowed small producers to reap some economy of scale benefits typically captured by only the largest players in an industry.

Pinduoduo also helped manufacturers customize their products. The direct relationship with consumers gave them insight into consumer behavior. They could cut costs by reducing demand mismatches, tweak clothing styles, redesign food packaging, accelerate product development timelines, launch entirely new products, and even integrate PDD’s data directly into their manufacturing lines. Similar to how marketers might use Google keywords to predict demand, Chinese suppliers could do the same. This process eliminated layers of middle men across a host of industries and let producers (many without their own brand) sell directly to consumers.

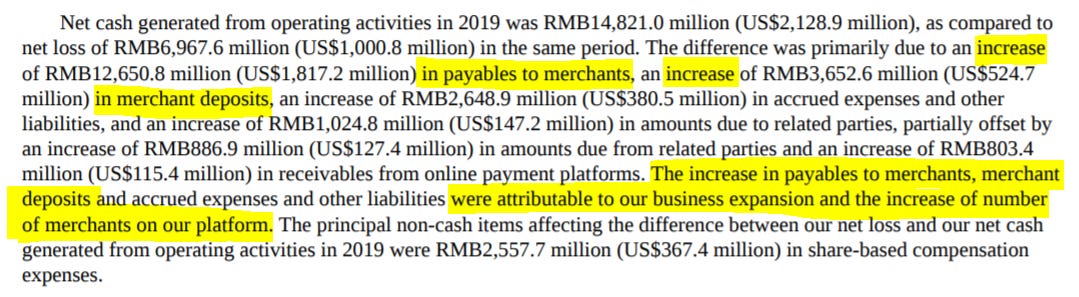

Suppliers paid Pinduoduo an upfront fee when first listing on the platform to guard against fraud (they were also fined 10x the value of any counterfeit goods they were caught selling!). They were required to pre-pay for advertising that was redeemed over time, and received payment from PDD an average of 15 days after the goods were shipped out of their factory. Since payments from customers were collected at the time of sale, this gave PDD a negative cash conversion cycle, or float, that collected cash before actually delivering any goods or services (as highlighted below).

For a company like PDD that might see its business grow 25-100% in any given month, receiving cash up front from consumers and paying its bills two weeks later had massive downstream implications on its capital needs. This negative working capital provided excess cash to subsidize user acquisition and allowed the company to mitigate shareholder dilution as it scaled.

This was all scaling at a time the Trade War with the US was evaporating foreign demand for Chinese manufacturers. Chinese exports slowed in 2018, and February of 2019 brought the lowest of Chinese export volume in three years. The COVID-19 pandemic to start 2020 also didn’t help foreign demand. The C2M model that was core to Pinduoduo’s business model began as a broader country-wide push to modernize the manufacturing industry, but increasingly became a tool to stave off a recession.

Many of the suppliers joining Pinduoduo’s marketplace were invisible-to-consumer factories that lost business selling products to overseas brands who then marked up prices 5-10x. They were familiar with online retail, had excess capacity, and some had even tried and failed to launch their own consumer-facing brands. PDDs ability to pool demand allowed them to sell similar volumes of products to consumers at similar pricing they were getting from big brands. These savings were then passed along to consumers and further reinforced PDD’s “more savings, more fun” flywheel.

Pinduoduo heavily recruited these local suppliers that were losing international revenue. It launched 106 of these “manufacturer owned brands” in 2019, and aimed to create 1,000 more in 2020. According to a Citi note “more than 1 million merchants operated on PDD’s platform to end 2018, but they include only 552 established brands. That compares with 150,000 established brands on Tmall.” Most of these manufacturers will gladly accept foreign demand when it returns, but will continue to benefit from PDD’s newfound domestic business.

Moving up the Consumption Stack

In 2018, Taobao had over 500 million users compared to WeChat’s 1 billion. The gap between the two represented mostly citizens in third-tier and below cities, many of them senior citizens.

This increasingly became a problem for China’s incumbent ecommerce players as Taobao’s penetration was as low as 1% in some of China’s smaller cities. Third-tier cities and below makeup over 50% of the population and are estimated to make up 66% of China’s consumption growth between 2020 and 2030. While upper-class consumers cared about international brands, this newer wave of consumers cared more about lower prices and quality products. Traditionally, over 55% of Singles Day GMV, or Chinese ecommerce’s annual discount day, came from third-tier cities and below.

Pinduoduo built its early business model around these young consumers in rural communities and China’s smaller cities. Meanwhile, incumbents tried serving them with drone delivery. PDD would first target rural customers around a city, get farmers and other merchants on board, and then move to the city center. In some cities, PDD saw penetration as high as 35%. Pinhaohuo’s initial user base was 80% female who likely drove most of their household purchasing decisions. For many of its earliest customers, PDD was their first experience using ecommerce.

Colin has said “People living in the five rings of Beijing wouldn’t understand our purpose. The new consumer economy isn’t about giving Shanghainese the life of Parisians. It’s about providing paper towels and good fruit to people in the Anhui province.” He uses Tian Ji’s Horse Racing Strategy as an analogy to Pinduoduo’s model:

Tian Ji and the king of the Qi Kingdom both like horse racing and race each other often. They frequently make bets. The king of Qi has better horses and Tian Ji loses every time. One day, Tian Ji’s friend says “take me to the race next time and I can help you win”. His friend learns that for every race, Tian Ji and the king both choose three horses classified as good, better, and best. There are three rounds, and the winner of the race is the one who wins at least two rounds. Both of them were using their “good” horse for the opponent’s “good” horse, “better” horse for the opponent’s “better” horse, and “best” for the “best”. The king had a slightly better horse in all three levels, and won every round. Tian Ji’s friend then brings up an idea: use Tian Ji’s “good” horse for racing the king’s “best” horse, then use the “best” horse against the king’s “better” horse, and the “better” horse against the “good” horse. As a result, Tian Ji loses the first round, but wins the second and third round, winning the race.

Similar to Tian Ji, Pinduoduo noticed that incumbents were overlooking lower income consumers. These consumers flocked to PDD’s low prices which allowed it to operate under the radar while building a model that allowed it to quickly scale up market, catching competitors off guard. In Q1 of 2019, 44% of new users came from first and second-tier cities. Over $1 billion in agriculture products were sold in the first two weeks of June (up 310% year-over-year), 70% of which were bought by consumers in these large cities. By November, 45% of PDD’s GMV came from Tier 1-2 cities.

The Ongoing Battle for the Chinese Consumer

By March of 2020, over 630 million active buyers had made a purchase on Pinduoduo in the past year. The app had 488 million MAU’s, with many still accessing its services solely through WeChat.

Pinduoduo’s growth did not go unnoticed. By 2018, JD launched its C2M site, Jingzao. JD also launched a near-clone of PDD’s app called Jingzi at the end of 2019, which specifically targeted smaller cities with team buying discounts.

Alibaba launched its Teja group buying app in March of 2018. It announced similar C2M initiatives two years later, with plans to integrate consumer data collection for suppliers into every aspect of its products. It's also focused on negotiating exclusivity with these suppliers to keep them off of Pinduoduo’s platform. Its agricultural flash sales platform Juhuasuan launched in 2019, headed by Jiang Fan (below, left), a 34-year old executive in charge of both B2B Tmall and B2C Taobao. Industry experts believed he was a candidate to eventually lead Alibaba and its battle against Pinduoduo; however he was recently demoted due to personal misconduct.

Startup competitors like Taojiji also emerged in late 2018, gaining 11 million users in two months. One year later it had 130 million registered users, but struggled with the retention PDD had mastered, and was out of business by December of 2019. All of these competitors burned hundreds of millions in capital to move down market towards a consumer base Pinduoduo had already secured. At the same time, Pinduoduo was spending to move up. Its entire business was built around this C2M model, meaning its value proposition for suppliers increased as it grew.

One of Pinduoduo’s primary strategies to move up market was TV ads. Many consumers knew of PDD but were skeptical of the product quality. They used exclusive product drops tied to specific shows, celebrity endorsements, aggressive promotions, and in-app countdowns to convince users to try the app. Starting with fruit, this built trust in what has now become 18 broad categories like clothing, household goods, appliances, and electronics - all of which have much higher prices and been long dominated by Alibaba. The below commercial aired on one of China’s hottest TV series, the Voice of China, exposing them to millions.

The strategy worked. In January of 2019, 37% of GMV came from top-tier cities. By June, this increased to 48%. In Q3 of 2019, users in Tier 1 cities spent 3.2x more per transaction than the average user. Young users opened Pinduoduo 89 times per month in 2019 (up from 84 in 2018) compared to Taobao’s 81 times per month. DAU’s were using the app over 20 minutes per day.

PDD’s marketplace model kept costs flat as incremental revenue on larger orders fell to the bottom line. These new users also aggressively invited their friends. This meant that, while paying similar ad prices, PDD’s ROI was almost always higher than its competitors. It consistently spends almost all of (and sometimes more than) its reported revenue in a quarter on marketing. This is essentially PDD using the two week float provided by the 5.1 million merchants in Q4 of 2019 (up from 1 million in 2018) to acquire customers before paying them out. It was significantly under-earning too. PDD’s revenue in Q1 of 2020 was only 3% of GMV compared to JD’s 28%.

What’s next for Pinduoduo?

Over the next decade, we’ll see Pinduoduo double-down on selling to Chinese consumers. They’ll add new gamified features that predict future purchases while building on top of sticky fruit orders, increasing order sizes, and driving prices lower. It will go deeper with proprietary supply agreements, continuing to build what’s equivalent to a PDD private label. We’ll likely see more products that pool demand to be sold to the highest bidder, and some that require upfront payments or have long payment terms that increase PDD’s float.

Pinduoduo started experimenting with travel deals in 2016, and officially launched a travel business in late-2019. These included tours, vacations, and hotel rooms. In June of 2020, it added trains and domestic flights.

Pinduoduo recently announced a move into real estate. Users paid a ~$1k refundable deposit to take part in a team purchase on a 1,000 unit property under development where 600 units were sold. It appears unrelated to the core business at first, but real estate has a high GMV and typically precedes many other large purchases made by new families. Similar to growing a fruit tree, we may see the company design a complimentary game around the process of building a house or town that ultimately concludes with a purchase.

In 2019, it began heavily emphasizing live streaming. Analysts project China’s live stream market will generate $136 billion in transactions in 2020, up 121% from 2019. Producers broadcast for free and partner with influencers to push garments, cosmetics, and household products. It’s relatively non-scheduled in nature and works well with PDD’s pop-up and flash deals. Consumers put more trust in the product quality when purchased directly from a live stream of the warehouse (below). Many of these warehouses featured foreign goods that had just cleared customs, inviting viewers to ship them directly to their home. And natural to PDD’s model, users earn discounts by inviting friends to watch.

A live streamed event in June of 2019 sold 400 cars over Pinduoduo in 18 seconds. PDD’s recently launched online pharmacy sells both OTC drugs and medical devices. It’s a market fraught with inefficient middle men and pharmaceuticals represent a recurring, sticky product like fruit. In April of 2020 PDD invested $200 million in appliance and electronics retainer GOME, who it now partners with for in-store product demonstrations. It's possible the newly launched DD Bank game precludes financing and insurance related to these larger products. And it will likely integrate consumer usage data directly into many of them, hinting PDD’s custom appliances may one day automatically restock food directly from its farmers.

We may also see Pinduoduo open itself for other retailers to tap into its direct relationship with manufacturers. It also appears to be doubling-down on helping foreign brands sell into China. Amazon may have taken this first step in both of these initiatives, opening a store in November of 2019. It featured 1,000 foreign brands across health, beauty, apparel, and electronics. Amazon has historically struggled in China. Its market share shrunk from 15% in 2012 to less than 1% by 2019. This partnership gave it immediate distribution to hundreds of millions of Chinese consumers. For PDD, it boosted its image within China, giving it instant credibility selling foreign-brands from a trusted source. It also gave PDD access to Amazon’s global network of suppliers and logistics providers.

Pinduoduo recently created its own logistics tracking platform. Similar to Alibaba’s Cainiao which PDD previously used, it won’t own its own fleet or warehouses and instead links together third party providers. It's already the second largest logistics network in the world behind Cainiao. This gives PDD more granular insights on package location and will let them optimize order routing. They’ve opened this up to third parties for free. Couriers will likely be able to bid on demand and earn revenue on previously empty trips like delivering products from an urban center into a village and then bringing produce back into the city. This may allow for faster deliveries and make PDDs produce even fresher. It starts a road down merging online and offline behavior, as described in this video.

Like many other Chinese tech giants, Pinduoduo rolled out its collaborative enterprise software platform called Knock in February. The main features include messaging, to-do lists, basic photo tools, and voice calls. It excludes features popular on other similar products like video conferencing, file transfer, and task / expensing approval. Everything is linked to the back-end of PDD, and hinting it will have benefits similar to Slack’s shared channels for many of PDD’s suppliers.

Colin is personally very passionate about improving the efficiency of Chinese agriculture. Pinduoduo is building 1,000 agriculture plantations which will expand it into coffee, tea, and walnuts among many others. PDD built custom software for farmers to run their businesses and launched Duo Duo University to teach them how to run a business and improve their crop yield. The Chinese labor force is aging, and the new wave of workers will want standardized workflows and quality control on their phones. More efficiency will further reduce PDD’s prices and make its product stickier with suppliers and consumers over time. Its not a stretch to think Pinduoduo could one day provide the software powering most of China’s agricultural and manufacturing production.

Pinduoduo has also started building more in-app games. One in particular is a Farmville-like game called Duo Duo Farm. Another is Duo Duo Crush, a Candy Crush-like game where nearly every action incentivizes a purchase.

One of their newest games is Duo Duo Piggy Bank. Users collect virtual coins by inviting their friends, browsing products, and completing tasks. Once they have enough coins, they can start manufacturing a product in the Dream Factory. This involves performing more tasks to generate electricity to keep the factory running. Finally, they earn extra fuel to expedite the shipment.

These are likely the beginning of many other gamified experiences Pinduoduo will build into its product over time.

Conclusion

Pinduoduo still faces some high-level challenges. China’s discount market has a noted problem with counterfeit goods that are popular with lower income consumers both on and offline. Despite being smaller, PDD generated more complaints than Alibaba’s Taobao and Tmall combined in 2017. A week after its July 2018 IPO, it met with government officials to discuss how to handle these complaints. Short-sellers have made valid claims that PDD’s financial reporting may overstate GMV and Revenue to US investors, and that its hiding employee costs in an undisclosed related entity. The company does not have a CFO (fairly common in Chinese tech), which doesn’t help these allegations. And Colin recently stepped down as CEO to move into a chairman role and began giving his stock back to the company to grant to other employees. Public market investors should be sure to do their diligence on these matters.

Pinduoduo’s rise has been nothing short of impressive. It represents a case study of an excellent team quickly building and scaling a transformational business. Like Amazon used books, PDD used fruit as a wedge to build what became one of the world’s largest ecommerce companies in five years. It went a step further than Tencent building games, or Facebook selling ads, and created an asset-light vertically integrated social gaming company. It built farmers, and eventually manufacturers, a business-in-a-box solution for operating their companies. And it entertained consumers while giving them low prices on products they buy everyday.

If you liked this, please subscribe above for more posts. I’m also on Twitter at @TurnerNovak. If you’re building a company that borrows elements from Pinduoduo, I have invested in numerous companies with similar models from pre-seed to pre-IPO, and would love to learn more at turner[at]bananacapital.vc.

Thank you to Hans at GGV for pointing me to early resources; Ben and David at Acquired for their excellent recent episode on Pinduoduo; and James at Lightspeed + @JoshConstine and @Leonlinsx in the Type House for feedback on early drafts.

Due to the potential inaccuracy and translation errors in some foreign publications, I cannot personally verify every figure shared here. I have linked to all sources wherever possible. This is not investment advice and I currently have $0 invested in securities tied to Pinduoduo.

I thoroughly enjoyed this from start to finish. I personally believe that when ever any market is going thru that consumption shift/upgrade, the huge opportunity lies at the bottom of the pyramid. We are witnessing this in India now and last month for the first time, data users in rural India surpassed the numbers in Urban India. I am trying to address that in an edtech venture by enabling the small tutors and institutions to compete with unicorns and large competitors. These small educators understand the pulse of consumers at the lower end of market and can fill the newly acquired aspirations.

Excellent work. I started a social shopping company a LONG time ago (maybe 10 years too early) and I wish I had implemented the lower-priced buy with friends option BEFORE you found your friends. Brilliant!