🎧🍌 How to Operate with Precision, with Itai Damti (Co-founder and CEO of Unit)

The two waves of fintech innovation, how Unit won in a crowded market by focusing on product and growing the market, his framework for leveraging investors, and how to prioritize time as a founder

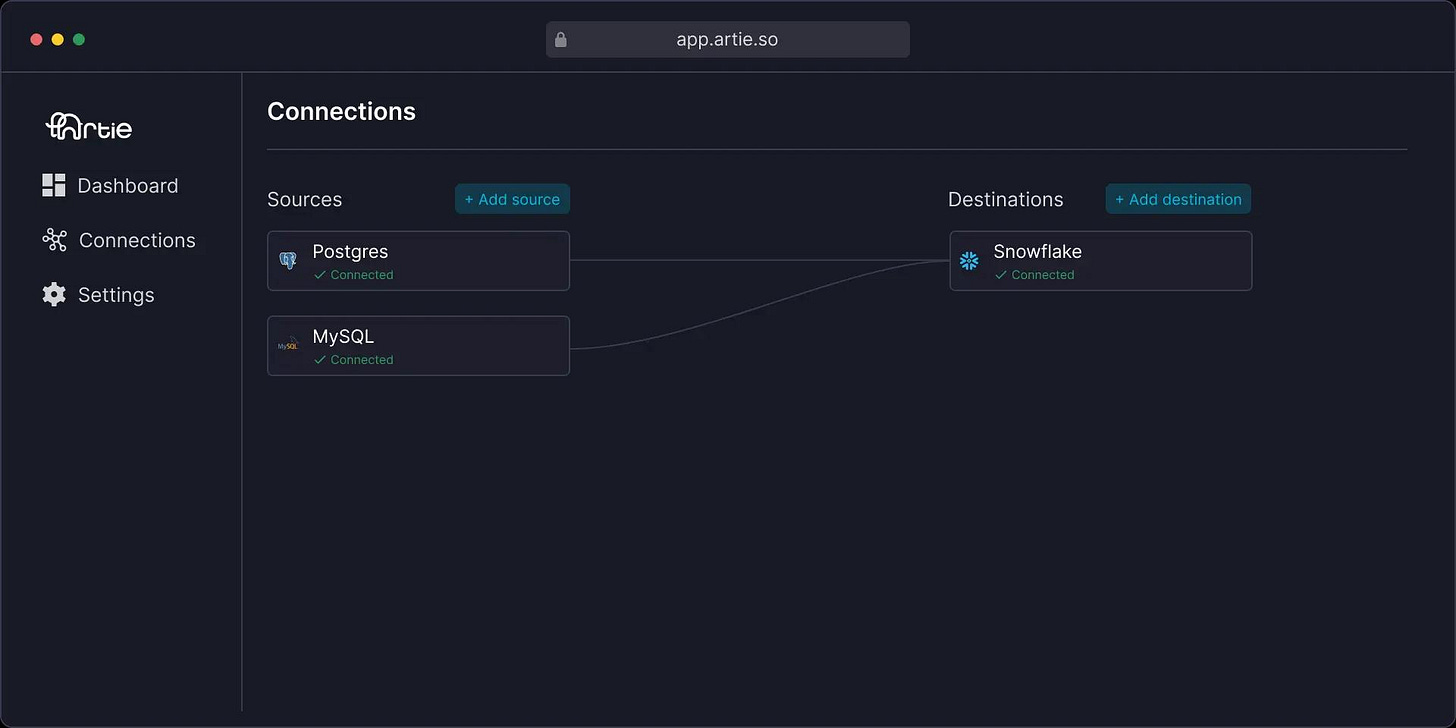

The episode is brought to you by Artie

Artie is the real-time database replication solution that sets up in minutes and requires zero day-to-day maintenance.

Artie is one of my latest investments at Banana, and I’ve been recommending it to every team I meet.

Artie uses streaming technology and change data capture to sync your databases and data warehouse in real-time. The product abstracts away all the complexity of setting up and managing streaming architecture, and enables you to operationalize your live production data. Its all wrapped in an Analytics Portal giving insight into system level infrastructure, helping you monitor database and pipeline health.

To go deeper, check out their latest case study with Substack.

Internal sentiment is extremely positive. Our A/B testing framework measures much faster and we have higher data integrity now. This means the whole company can move faster and make decisions quicker. Artie is business critical and our day to day would be significantly tougher without it.

Artie is open source, and you can book a demo here for a two week free trial.

To inquire about sponsoring future episodes, click here.

Itai Damti is the Co-founder and CEO of Unit, the platform that helps leading tech companies store, move, and lend money.

Unit has raised over $170 million from investors like Better Tomorrow Ventures, Accel, Insight, and dozens of angels.

Some topics discussed include:

The first and second waves of fintech innovation

Why the next wave of financial services is moving inside of software

How Unit beat the competition by focusing on product and expanding the market

Itai’s framework for leveraging investors

His strategy for prioritizing as a founder

How Unit operates with precision

Why they haven’t built any crypto products

And lots more!

Find Itai on Twitter and LinkedIn

🙏 Thanks to Zac and Xavier at Supermix for help with production and distribution.

Transcript

Find transcripts of all prior episodes here.

Turner Novak:

Itai, how's it going? Thanks for joining me today.

Itai Damti:

It's good to be here. Hey, Turner.

Turner Novak:

So diving right in. First question, what is Unit? Can you real quick explain for somebody who doesn't know?

Itai Damti:

So Unit is an embedded finance platform. We help over 200 companies build banking and lending into their products. Our customers include AngelList, Build.com, Homebase, and many others. Today we're a team of 160 people between New York, which is where I'm based. In Tel Aviv, which is where my co-founder and the engineering team are based. And in terms of funding, we've raised 170 million to date from top VCs, including Insight, Excel, Better Tomorrow Ventures and Long Tail of Angels.

Turner Novak:

That's amazing. I think we're going to talk about some of those in a little bit. So I thought the first place to start, most people would say that Unit is a banking as a service company. Can you explain what that is and then why you actually don't like that word and how you think about it internally?

Itai Damti:

What we do as a company is we help tech companies build banking and lending into their products. If you think about it in the most broad way, we help companies store, move and lend money to their end customers. And it turns out that adding those software companies to the distribution chain of financial services is a very, very hard problem, not only for them but also for the banks that power them.

And over time, this industry had many shapes. It started with a lot of prepaid cards that companies launched on top of banks. If you look at what United did with United Card, it's also a form of partnership between a financial institution and a non-FI company, a non-financial company. In the recent five years, I think people started talking about it as banking as a service, meaning there are 50 or 100 banks in the US that allow you to use their rails and park money and move money and lend money with their help.

And so the ecosystem developed with this terminology in mind and what we now think about when we think about these use cases is banking as a service doesn't sound like the right term for a few reasons. One, it's very supply-centric. So if you think about what's the actual use case, what is actually getting built? It's embedded finance. It's finance or financial products that live inside software. And that's how we like thinking about it. The other reason that we don't like using the term as much anymore is that it really describes a lot of different practices and many companies that do not operate like Unit in terms of the business model or the legal constructs. And we like to really look at how those products live in context and celebrate embedded finance as the next wave of innovation in financial services.

Turner Novak:

There's a lot to unpack there. So I've heard you mentioned there's these different waves of FinTech innovation in the U.S. Can you describe those to us and how of how those have played out?

Itai Damti:

Yeah, so let me start by maybe adding one more point to my first answer, which is unlike other places in the world where companies can innovate without working directly with financial institutions in the US, the regulatory landscape is such that in order to move money or store money or lend money, you have to work with a financial institution or have certain licenses for certain activities. But the model in the US is very much that a bank must be there behind the scenes and they must have oversight over how you operate.

Turner Novak:

Do you know why that is, specifically in the US versus not somewhere else? Do you know how that happened?

Itai Damti:

If you think about how money actually travels and gets stored in the world, it's always a bank. So if you look at the evolution of financial services historically it might've been different back then or when cash was more used. But today, when all money in digital is digital, all the money in the world lives in central banks and central banks hold all of the money in their economies, whether it's in Nigeria or Malaysia or UK or US, it's all in one place. And then banks have this system of keeping track of how much you and I own in the US and reflecting it back to us. So the nature of financial services is eventually, if you look all the way to the bottom, very centralized, all the money lives in one database that belongs to one bank, which happens to be the central bank of the country.

What happened in other parts of the world is that regulators found a way to allow companies to operate with more novel and lightweight licenses. In the EU you have this construct, it's pretty fresh. It's as of the last 10, 15 years, tech companies can... They will ride on banks, they will use the bank rails to move money, but they can operate with a more lightweight license. They do a lot of these things independently without depending on banks. I would say in the US the reason that the situation is that you have to work with banks is that there is no novel framework yet that allows for tech companies and other kinds of companies to operate more independently and not depend on banks. So the equation is very much that every financial product that gets built is hosted by a bank or manufactured by a bank.

Every dollar that moves is moving from a bank and to a bank. And then the banks are very much in the overseeing position. They have to see how those tech companies operate. So if you have a Chime or a PayPal or a Venmo or Lending Cloud or Betterment, every dollar that moves on their platforms is subject to bank oversights and banks in turn are subject to regulatory oversight. So I just think that this ecosystem remains in its legacy structure in the US and it works. There is a lot of money that moves and innovation that gets built, but the vertical form of innovation where tech companies have to be built on top of banks is in my opinion here to stay.

Turner Novak:

Is that impacted how the market's evolved? Because think you've talked about these two different ways of innovations, the first wave if you want to hit on that, and then the second wave, did it impact those quite a bit? Just the structure of the market?

Itai Damti:

The type of demand that exists for storing, moving and lending money is very different today. So maybe I can start by unpacking what we think of as FinTech 1.0 and then FinTech 2.0 and then how do the banks and the tech companies communicate in those different waves? So first wave, think about 2008, 2009, companies like Venmo and Lending Club and Robin Hood all got started. And then their job was to challenge the incumbents and beat the big financial institutions in distribution before the big institutions get innovation. So each one of these companies had one product that they focused on and they tried to do it better, faster, cheaper, and you can see that some of them succeeded, some of them have scaled and became household names. There are hundreds of companies that struggled to fight with the economies of scale and the distribution of the big banks.

And that shape of innovation, what we call FinTech 1.0 is in my opinion, coming to an end because nobody's funding the next Chime. You're an investor, I'm betting you're not going to resonate or respond well to someone that says, "I want to build the next Chime in 2023." What we think has started about five years ago is a second and in my opinion, much more meaningful and impactful wave of innovation in which financial services start living inside popular software products. So if you think about what Shopify is doing in financial services or a company like Toast is doing in financial services or Lyft or Uber, all of them are taking advantage of the fact that they have very, very successful software ecosystems and they have better ways to give value and capture value if they put dollars inside the software and even put loans inside of the software.

So if you think about these type of demand, few things come to mind in my opinion. One, is that there are tens of thousands of companies that could be in that position in the future. Today it's a couple of thousands, but over time I believe that many business centric software companies are going to want to absorb dollars and move them into their software. That's one thing. The second is that unlike FinTech 1.0, I do believe that this time those companies have an unfair advantage in succeeding in financial services. For someone like a Chime to fight with JP Morgan or Citibank was a very, very long journey, a decade plus. But for someone like Uber or Shopify to succeed in financial services could be a two-year journey. And there's an interesting thing, which is none of these companies wants to take 30% of JP Morgan's market share.

They each want to take 0.1 to 0.5%. Shopify represents a fraction of the economic activity in the world, but because they serve shops and do it so successfully, they're in the position to really roll out loans and bank accounts and expense management solutions and other forms of financial services to those companies and succeed. And so our realization was that when you look at those new builders, the Shopifys and the Toasts and the [inaudible 00:11:53] of the world. They need something much more out of the box than the old players. The Chimes and the Venmos and the tooling that they have looking at yesterday's ecosystem are not going to be sufficient for launching and succeeding in financial services. It's just too much brain damage for them. Toast cannot deal with the same level of brain damage as a Chime because their focus is not singularly bank accounts.

Turner Novak:

Yeah, their focus is point of sale systems and building products for restaurants, essentially. Not being a financial services company.

Itai Damti:

Correct. And I think Shopify is another good example. Shopify is in so many different kinds of businesses today. They're in logistics and they're of course in the store operating system and payments and catalog management and inventory, et cetera. So they're building so many different aspects of the day-to-day that those shops need that if they launch financial services, they don't want this to look like the launching of Chime. They want this to be more plug and play. So leveraging your software into software plus finance is a journey, and that journey must be manageable for those companies. If you raised a hundred million as Chime over time, you could build a compliance team, the bank relationships and the engineering that it takes to stand up Chime. But if you're a company like Shopify, your whole job is to do it quickly and luckily there is infrastructure today that allows them to expand into it quickly.

Turner Novak:

If I'm a listener, I'm lost, I'm like Shopify, how do they incorporate financial services? This is a question from Nik Milanović at This Week in FinTech. Can you just give us some examples of what Unit's product might look like in the while for a Shopify, for a Toast, any of these companies that might use it?

Itai Damti:

Sure. So let me start with Shopify who has done this for many years and continues to get better at delivering financial services. And then I can speak to maybe one or two use cases within Unit and add some [inaudible 00:13:43]. I do believe in giving examples to help people visualize what's being built. Think about Shopify. Shopify started many years ago. They've launched an operating system for online shops. Over time, they've delivered a lot of what you need to run an online business, including as I said, marketing solutions and payments, acceptance and storefront and catalog management and discounts and all sorts of things that make you more competitive and more successful in what you do. When you have so much connection with the end customers. And when you act as a one-stop shop for all of their needs, there could be a very interesting opportunity to launch financial services to make them even more successful and to make more profits.

So what Shopify has done over the years, in addition to payments acceptance, which was the first step, they've launched Capital Solutions and they got themselves in the position where they know your sales cycle and they know how much revenue you've been making in the last few months and what are you selling and how your category is performing. And they're in a great position to know that it's safe to extend a $5,000 loan or merchant cash advance to allow you to invest in inventory, allow you to hire someone, allow you to market your shop. And so they've built this ecosystem that includes not only the shop operating system, but also a new button that says, "Click here to get a $5,000 cash advance and invest in your shop," and you can spend it in multiple ways, but best how to spend it or just underwriting and giving you that capital solution.

That's one thing that companies do. On a long enough timeframe we find that companies that lend, just like the example I gave, are also banking those customers. So Shopify has launched a bank account for their merchants in addition to the Capital Solutions. And then of course you can do a lot of interesting loyalty plans and actions where you give people cheaper loan if they use the bank account or you give them a bank account with instant payments if they choose to use the loan. So the journey of all of these software companies from becoming just software to speaking the language of money fluently and giving the money meaning for you, for the online seller is a very, very long and lucrative journey for you and for them.

Turner Novak:

So I guess to summarize it all, it's basically this first wave was they were building products and the second wave is they're using their distribution to offer the same products essentially that maybe some existing incumbent financial services companies might use, but they don't really have to go separately acquire these customers for a financial service product. It's just you get some of the same revenue, some of the same cash flow margins, but they're bundled in the rest of your product. So it's a pretty compelling pitch to them or pretty compelling decision as a CEO founder or product manager. We need to do this. This is a pretty crucial part of our business model.

Itai Damti:

The revenue opportunity can be as big as two x or four x in revenue expansion per user. If you deliver those financial services in the right way, the stickiness of those customers becomes very, very high because they're enjoying the financial services that you allow them to consume and use in the platform, and you can also really create a convenience effect around their day-to-day. So if a business is using Shopify to pay vendors or get paid from other customers outside of Shopify, you can really create a one-stop shop and sell convenience in addition to monetizing financial services. I think the interesting thing when you said that you contrast this with the Chase or Citi option for that merchant, I think that there's a major difference between FinTech 1.0 and FinTech 2.0. Think about Citibank. Citibank I don't think was very afraid of Chime because Chime really climbed a massive uphill to get to their current level of distribution.

Chime is a neobank, they try to challenge the big institutions and they had to work their way from 0% distribution to whatever it might be, five or 10% today. But think about the equation as it applies to Shopify. Shopify has two massive advantages over Citi. One is that all of the customers live inside of Shopify, they log into the store every day, they manage their finances, they look at their money moving, and the only thing they need to do to park money in Shopify is say, "Yes," and accept the terms and conditions.

So the distribution advantage is no longer with incumbents, it's now with the tech company. So that's one way in which the equation flipped. Another way in which the equation flipped is it used to be, again, the advantage of the big institution that you and I walk into their branch and we get services and they know you, they know me, they know what the consumer checking account looks like, but in the case of an online store that uses Shopify, what does Citi really know about that store? If they open an account, they know nothing. They know that it's a business, it's incorporated in Delaware, but they know nothing about it outside of that.

Shopify knows everything. They can really give you a loan because they know your seasonality, they know your trends when it comes to revenues, et cetera. So they're in a great position to really win this time. And I think the shape of innovation in the next 10 years is going to be that instead of fighting 10 companies like Venmo and Chime, the big institutions are going to be facing tens of thousands of companies like Shopify that really succeed in their small niche in the economy and give a one-stop shop to those companies and those customers, including financing, including banking.

Turner Novak:

If I'm Shopify and I'm giving a loan to one of my customers, where does the money for that loan come from in my Shopify? Am I doing it off my own balance sheet? Am I raising separate funds? Am I partnering with Citi or Goldman Sachs? How does that usually work?

Itai Damti:

It really changes per use case. In most cases, when companies operate at scale like Shopify, they have their own bank relationships and capital markets desk that basically raises money and from outside investors who give debt and then uses the money to give it to small businesses and collect and replenish this reserve. If you look at how companies like Brex and Ramp operate pretty much the same way. They have a bank relationship, but they also have a team of people that is responsible for raising hundreds of million, millions in debt that they can use and put to work. In this particular case, I would say Shopify is probably using this type of structure, but for many companies that now compete with Shopify and don't have those resources, but they have the data, they have the distribution, they have the software, they have the trust of the end user, there is a better way to do it, and this is what we're trying to help them stand out.

Turner Novak:

Okay, so then Units service, are you also going out and raising capital and helping fund the movement of money or do you partner with some of the banks that you're working with?

Itai Damti:

Yeah, so this is a question that's specific to lending. In lending, we have two options. The option we started with was actually pretty high friction for the customer. We asked the client to use their balance sheet or to bring some outside source of capital. Using your balance sheet as a small company, let's say a series A company, when you have 12 million in the bank, that's not necessarily the best use of funds and you're not even sure if you can underwrite effectively. So that's really the first version of the lending product we launched.

The new version is a second option that we now put in front of companies, which is you can use our own underwriting and capital solutions so that you don't have to be in the underwriting and capital position. So you can extend these loans to small businesses. We have an engine that calculates the eligibility and then we allow them to then get a credit card and go spend up to X number of thousands. We do it only for businesses. We don't have any involvement in consumer lending these days. We do it with partners. So the capital and underwriting solutions we have are partners-based.

Turner Novak:

So this was another question, I think it was from Nick. You are not Shopify without the actual touchpoint relationship with the customer. If you're lending the money, how do you understand, do your customers typically... You have the integration, you can see a lot of the same data. Is that how it works?

Itai Damti:

We can maybe take a specific example. There is a company called Highbeam that built a dashboard for online sellers and basically a bank account for online sellers. Their V one was a bank account and many companies start with Unit with just one of the two legs, either banking or lending. Different companies make different choices, but they started with the banking solution and they've built a lot of software to allow you to see where are you selling, how much are you selling in each channel, what's your spend and profitability and really allow you to manage your expenses in one place. That was V one. When the time comes for them to launch any lending products and or credit cards, they basically tell us that this is their intention. We identify the right type of product. Sometimes it's a credit card, which is a unique form of loan to a small business, and the second is maybe we want to wire them the money and just make the money land in their Highbeam account.

So first of all, we profile how it needs to be delivered, what's the best mechanism and what's best for the end customer, and then we allow them to basically make API calls to Unit. After going through an onboarding process and making sure that the compliance side is tight, we allow them to make API calls to Unit and basically extend loans to the end customers. Behind the scenes, there's a partner bank that powers this offering and provides the oversight, which is the regulatory side of the house. So we basically make sure that the Highbeams of the world can launch these solutions and they can log into the same dashboard as their banking offering.

They can click on an end customer, they can see here's the deposit account, it has $8,000 in it, and here's the credit account, which is 5K limit and 60% has been utilized. They can see all of that in one place, but behind the scenes, the banks have access to the same data and they see the lifecycle of those loans. They can see that credit of 5K was extended in October 1st. By the end of October it was 60% utilized and then fully paid. We mediate this experience in terms of software, but we try to keep it very simple for companies like Highbeam.

Turner Novak:

How simple is it to, if I'm not using Unit, create the ability for someone to open a bank account? How simple is that?

Itai Damti:

Yeah, I would say banking and lending have unique dynamics, so we do both legs, but we definitely recognize that lending is a bit more complex and bespoke. If you ask one or two people that have launched lending companies in the past, what did it take for them to launch their companies? They would say anything from 12 to 18 months to the first dollar they've extended in loans. Those products are pretty hard to build. If you look at banking, I would say with modern infrastructure, you can do it in a month or two and do it with full bank approval and oversight.

Turner Novak:

And this is with third party tools?

Itai Damti:

It's a very plug and play experience for you because don't have to make a lot of the decisions on identity solutions or how to generate statements or how to reflect that. We help you make sure that fees are reflected in the best ways and included, and we just deliver it to you in a way that's more out of the box. But if you contrast this with how Chime was built, Chime as a company probably needed a year plus to deliver the first bank account that anyone could launch, could park $8 on, and then cards and other types of financial services are being layered on top of that.

Turner Novak:

So then there was probably a point in time where it didn't make sense for Shopify to open bank accounts do lending. It was probably a distraction maybe from the core product or just very complicated. And then at some point with the switch to finance or FinTech 2.0, it's almost like, "Wow, it's so easy. It's a no-brainer. We have to do this."

Itai Damti:

Yes, I would say they did it in the old-fashioned way. So the scale of Shopify and frankly the visionary thinking behind the company was such that they could afford venturing into financial services and do it in the most heavy way because they've built their offering about five or six years ago. As you look into the next five or 10 years, companies don't have to go through the old-fashioned way. They can plug into a modern financial infrastructure.

The bank needs to be very involved, but they have an equally high quality view into how you operate. And this connection between the tech company that's building and the bank that's providing the services behind the scenes becomes a lot more streamlined. So the options exist today. I believe that infrastructure is also an enabler. If it doesn't exist, things don't get billed. It exists. There's so much more that could be done and people do it eventually. So I'm very excited to put something like this in front of people and have them think what becomes possible.

Turner Novak:

And you had this really interesting point when we were talking through some of the examples earlier of it's not just financial services that people are embedding, it's this concept embedded everything. Can you dive into that a little bit more and where Unit sits in that whole puzzle in that market?

Itai Damti:

So this is a relatively fresh thought and framework that I use to think how the next 10 years are going to look in business software. This is bigger than Unit. This is something that I realized at some point that we're talking about embedded finance all day and we're thinking about banking and lending and banking and lending and making it better. But if you look zoom out, I think something really interesting is happening in the business software world, which is more and more companies are becoming a one-stop shop for their end customers.

There are companies like Shopify that do it for sellers. There are companies like Uber that try to be more and more dominant in the financial health and financial lives of their drivers, for example. And there are companies like Baseline or Roofstock that we serve that try to be that, but for landlords. And there are companies that do it for nonprofits and there are companies that do it for construction companies, there are so many vertical SaaS companies being built that really try to be an all-in-one solution for their customers and on a long enough timeframe.

If you think about a company that serves a set of nonprofits, let's say you want to build the best operating system for nonprofits today, it probably should include in five or 10 years everything they did, their CRM and donor management system and maybe even activation of people that they recruited to their communities. Of course fundraising tools and other back office tools and mailing lists that help them communicate with the world and maybe a website. If you think about what every business needs is, they eventually want to get everything in office. And this is something that I think about as embedded everything.

I think that those apps, the Shopifys and the Toast of the world are going to be the very successful layer of, call it 10,000 companies in 10 years below them. There are going to be companies like us that help with embedded banking and lending or maybe embedded insurance or maybe an embedded Salesforce or maybe an embedded Monday and embedded accounting and payroll. And so those companies, the Shopifys of the world are going to be consuming infrastructure from those infrastructure companies that do embedded something. And then Shopify will then enrich its user interface with accounting, with payroll, with banking, with lending, with insurance. And I think it's very powerful.

Turner Novak:

Yeah, I guess so if I'm a local nonprofit, maybe I'd help solve food shortages in Alabama. I'm not an expert on really any of the things you just touched on, but I'm really good at building a relationship with people in my community, and that's probably not what Unit is good at. You're not good at how do you acquire a food shelter as a lending customer, it doesn't really make any sense for you. They're probably not a big enough customer. So you acquire some of these bigger entities that are then experts at serving a specific niche customer. And it's probably better for the customer too. It's better for you, it's better for everybody.

Itai Damti:

Because then we are not building anything that speaks the language of the nonprofit. We are building generic storage movement and lending rails, but those companies that build operating systems for businesses, again, they could be medical practices, they could be construction companies, they could be nonprofits. They give them money, meaning they know that transaction X where you have an outgoing payment via cheque, could be to vendor that you pay locally or that if you had an invoice paid or a donation, they can give the money meaning when it comes into your account.

So I think the meaning of money is becoming something that I'm very passionate about. We are not giving money, meaning the companies that give money, meaning are the companies that build operating systems. And so I think about the future internet or the future business software world is two layers. Again, those 10,000 companies that look like Shopify or give butter in nonprofits or anything in their vertical, and then there are probably 200 companies like us that are being built.

I think about it as the silent giants, like the companies that nobody knows but power a lot of the embedded features. I think there's still a version of embedded Asana that's waiting to be built. I think there are people working on an embedded QuickBooks. People have solved the embedded Gasto problem. People have done embedded insurance. So I really think about those 200 companies as really important utilities that then power the software that gets built on top of them. And if you're a nonprofit, you get a one-stop shop in give butter, and it has 20 different things you need and pay for, but it's powered by all these underlying tools that power me butter in turn.

Turner Novak:

And probably going out and figuring out an insurance policy, having the people that run the nonprofit that's not valuable for the people they serve. If you can give them all these kind of different tools that they may be stitching together manually, you can enable them to serve their mission even more effectively.

Itai Damti:

Agree. One of my favorite use cases in the Unit customer base is a company called Baseline. Baseline is building a one-stop shop for landlords, independent landlords, not large one. So if you have two or three units somewhere in your city and you want to manage everything in one place, they allow you to basically enter those units one by one, they set up bank accounts for all these different units, and then you can buy insurance for each unit when the time comes and you can park money and spend money. And the meaning that the money has is incoming rent payment or outgoing utility payments or this is an investment in furniture that's going to increase the property value. So you have all these different kinds of money, meaning that they give the money, but also they sell insurance very, very successfully.

A lot of their revenues do come from insurance and they do bookkeeping. So you don't have to run Excel files for yourself to do your books, and you might have three different LCs. So it's pretty complex if you're just an individual. So I really think about embedded everything as the future and insurance is just one example and it's a one click purchase for you. If you have two apartments in Philadelphia, they know what insurance is going to meet your needs best, and all you need to do is accept the offer and they can manage the payments.

Turner Novak:

So a little bit of a different topic, but still on the same line of thinking. Question from my friend Sheel at Better Tomorrow Ventures, "What are some interesting things that you've learned about how the banking system works or financial services work that you didn't know before you started Unit?"

Itai Damti:

I think that really how commoditized banking is always striking. So the way I describe Unit is we do the undifferentiated stuff and the people who give money, meaning are those customers that we serve that then build money into their software again for medical clinics, for spas, for nonprofits, for construction companies. And I think it's hard to appreciate how useless bank accounts are without this context.

When you're an online seller and you log into your Chase account, Chase doesn't speak your language. They don't know what's an inventory purchase, they don't know what's payroll, they don't know what is marketing investment, but when you log into Highbeam or Shopify, they give all these money movements a meaning. So I think people glorify money storage movement and lending on the infrastructure level, but I don't think what we're doing is glorious at all. I think that it's not interesting in many ways.

I think that people who make money interesting are the companies that bill on top of us, and that's the reason that we're proud to power them almost in the same way that Stripe is powering payment acceptance for many, many merchants, they do the hard and undifferentiated problem of accepting payments, but the nonprofit really makes it interesting because they collect donations and this other company is collecting other types of payments to operate its activities, etc.

So Airbnb does it for the landlord. So I really think that it's really striking every time how much meaning those companies can cast into money and how deprived of meaning and boring money can be if you just look at the base layer. We're not going to do a lot of things. Unit cannot innovate in a thousand ways. There are only three or four ways to move money in the U.S. It includes ACH cheques, wires, cards, and we support all of them and we can support instant payments very soon. And there's not going to be infinite ways to move money and store money, but what gets infinite is really the packaging of money for millions of businesses and individuals. So that's one thing that keeps striking me. It's just the realization that money movements are not interesting in themselves. It's when they have context.

Turner Novak:

This is actually, I didn't think I was going to ask you this question, but you just brought it up. What is the difference between a wire and ACH?

Itai Damti:

Plainly speaking, wires are a way to send money to people, and this is an irreversible transaction. So if you pay a rent, you log into your Chase account and in your Chase account you have this ability to send money out, and when you send it's irreversible. The money is out, there is no way to claim it back. ACH is a slightly different protocol in which you can both pull and push money.

So you can pull money actually from another account. That's how you pay your rent. In many cases, you just put your details and then somebody pulls money from it every month. This is by definition is an ACH. Plus there is all sorts of reversibility and guarantees and flexibility in this network that exists. ACH is older, so it really has a lot of flexibility and depth of payments. But think about wires as more expensive, one-sided, push only, and ACH is cheaper, two-sided or at least you can reverse payments and push or pull.

Turner Novak:

Okay. And then are wires quicker? ACH takes a little bit longer?

Itai Damti:

Yes. Oh yeah, that's another one. So wires travel as fast as instantly, depending on the institution, they can be there within minutes. And ACH is a batched network. So if you submit an ACH payment at 10:02 AM, it could be that your bank is going to wait four hours because before actually pulling or pushing the money to this other institution.

Turner Novak:

So then in terms of Unit specifically, do you remember what that moment was when you realized this is what you're going to do? What was that initial insight?

Itai Damti:

Daron and I have known each other for 20 years. Daron is my co-founder at Unit, and we've been building for 18 out of those 20 years together. Initially as part of the Israeli army, we were both software engineers in a little unit, and then we started our first company together in 2007. We subsequently spent a decade at that company. The only break we had from each other really was in 2018, in a part of 2019 when we both tried to start our second companies and failed independently. And then we got together to start Unit. We really wanted to work together. We were pretty flexible about what we're going to build, but we wanted to build another company together. We wanted to do some things differently this time that I can talk to in a bit. And then we championed different ideas and developed them to medium cooking and then chose Unit and really ran with it.

I think it's really the realization that it was so hard to build FinTech in 2019. I mean, when we looked at the ecosystem and if you squint and really try to envision how money is going to live inside software in the future and that all these companies are going to need solutions, it was impossible that they can do it with the all tooling. They cannot do it with the technology, the requirements and the bank set up that companies like Chime had. So that was what convinced us. I think the market size was considered very, very small back then. And I still think that it's a developing, yeah, I mean it's a developing market and I mean now we think about it as a bit more abundant and more common, but back then the thought that companies would store move and lend money in their products was pretty fringe. It was very exotic.

And I remember we had so many logos in our seed deck in 2019 that it really seemed like we're a bit crazy and pitching a sci-fi world to investors. But now if you look at many of these logos, they actually became Unit customers. And one special slide that I made without talking to Etsy was the Etsy seller dashboard re envisioned and re imagined for the money language. So that's something we did in 2019, and we really tried to visualize what things could look like. And I think people bought it back then, but it wasn't so important for software companies to speak the language of money, and now it's becoming clear that it's the future.

Turner Novak:

It probably seemed crazy at the time.

Itai Damti:

Yeah, it's still somewhat futuristic, but I think there's an interesting dynamic in different segments where there is a first mover. So Shopify was definitely the first one that moved with online sellers. And then many companies in their category are rushing to match their offering because they want to capture as much of the end user business and they can't be behind. So you think about how phones evolved to be what they are today, like smartphones. Camera was something that existed in very few products in the beginning, and then everybody needed a camera so the camera makers became important, and those things ended up becoming table stakes. I think those competitive dynamics really warm different verticals and were just excited to see it happening. But in many cases it's still considered a fringe idea and I think it'll become more and more obvious over time when you see these companies succeeding. It's really connecting the dots between software and finance.

Turner Novak:

And you mentioned putting together the pitch deck for the seed round. I think you raised 3.6 million October of 2019. What was some of the pushback that you got from people when you were trying to raise that very first round?

Itai Damti:

It was all over the place. I think market size was a real struggle back then, and it's true. We were making a bet on the market expanding tenfold in the next five years and maybe a hundredfold in the next 10 years. And that's something that I think has played out. And more and more companies are becoming users and consumers of these services. So that's one. So that by far was the biggest pushback, I think. The other pushback was that the category was frothy, that there were maybe three, four players in that space. Some of them seemed to be dominating the space or maybe well known in the space. But I think what investors miss is that there is an opportunity to educate the next 1000 buyers. Again, if you look at what was there back then, it was mostly companies that spoke to the old FinTech variety.

It was companies that spoke to the language of Chime and the language of Venmo, which was right for the time. But I think what investors needed to ask was who is the team that has an outsider's enough viewpoint on this space that they can actually shape buying decisions in the next five to 10 years? And I like being an outsider. I mean, I've been building FinTech for 15 years, but I was a complete outsider to the banking system when we started doing it. And I think it's an advantage in the same way that building Lemonade as a non-insurance person was an advantage. They could just reimagine and think from first principles. And so I think that the real challenge will continue to be how do you educate the next 1000 buyers as opposed to how do you build systems for the old days in which you had 50 buyers or 60 buyers that knew what to ask.

I think we were also, we didn't have the credibility of a team that has operated in the U.S. for decades. We've been operators for 15 years now, but I think that people like to see this endorsement stamp that you worked at Stripe or you worked at company X. And I don't think that it matters if you're hardworking and smart, but I think investors really need to see this stamp. And in many other situations, we would've gotten more of their vote of confidence if we had those stamps. And Sheel was actually able to see beyond that because he can identify a chip on your shoulder and he can really bet on people who are underdogs.

Turner Novak:

Sheel led the round, correct. I think we want to get that in the record. Yeah. Okay. How did you decide just who to bring in? And maybe this is not just related to your seed round, but just throughout the life of the company, how did you think about who you should raise money from and then how to leverage them?

Itai Damti:

So at Unit need, one of the favorite principles we use all the time is precision. We like identifying sharp problems and designing sharp solutions and really boil it down to what's needed. And I think fundraising has the same dynamics where at seed you need something very different from A and from B and from C. And I think if I can summarize maybe in one sentence, what guided us over time. Seed, you want really empathetic, really smart, really flexible investors. So that's what you're optimizing for. You're going to be lost, it's going to be really open-ended and amorphous, and you need people you can consult with to get through this first mile.

Series A, the name of the game is company building. How do you start putting processes and structure in place that really make you more structured and scalable as a company? Maybe not to the extreme, but to the point that you can call someone and ask, "How do you structure a sales team? How do you compensate salespeople? How do you think about the relationship between success and product and how to build the most effective communication mechanisms between them. How to scale an engineering team, et cetera. Hiring processes," there are many, many questions that come up.

So we chose Aleph, which is an Israel-based fund. They're a force of nature. We knew that they were best for that job when we had multiple term sheets and we took their money and decided to build with them because we knew that this was their superpower. Series B, you're starting to think bigger. You're starting to think about what does it take to really think about becoming a public company one day? How do you create discipline on the board level and scrutiny from the board and from your late stage investors that's going to push you from 10 million in revenue to a hundred million over time.

And I think you're looking for discipline pattern matching. Ambition I think is very important. And we chose Excel. And then series C was Insight, and Insight was really the investor we chose to guide us through the hyperscale process. I think with each one of these rounds, I mean it can change per company. I think if you're a FinTech company, there is a lot of need for initial connections.

And actually it's always the case that you need some hustling in the early days of a company, but especially in FinTech. So people like Sheel make a lot of difference and make the right choice. And then over time you just have these changing needs and you need to be precise about what money you raise. At the end of the day though, I do believe that 99.99% of the outcomes in companies is purely based on founders.

So I also don't want to over index on the type of capital you take and how you activate people. I think it's mostly about how you execute. And I think it's harder to change how you yourself... You can select new investors and you can introduce new DNA to your investor set. That's relatively easy because they do it organically. How do you change your own mind? How do you become a new type of CEO every three to six months? How do you introduce process to an environment that doesn't lend itself to process today or structure I think is very, very important. That's the harder job. That's more of a mental job.

Turner Novak:

I mean, you go from this crazy chaotic startup where things are changing hourly maybe to now it's you're trying to build a corporation like a large entity, publicly traded company. Eventually if you're successful, there will be thousands of employees. It's inevitable. So yeah, it's a good point. So you raised the seed round. There's this concept of partner banks. You've mentioned this a couple of times. Can you really quick explain what that was and then how that went getting your first partner bank?

Itai Damti:

Yeah. So we raised in October 2019. We were insisting to be just two people in the company until we land our first bank relationships. Precision is very important to us so our version of payroll precision was just two people. One of them needs to impress banks and make sure that they're bought in, and the other one builds V one of the sandbox and the systems. So Daron did the building. I did the roadshow and met banks. I was lucky to meet banks in person at the end of 2019 and early 2020, and then Covid hit. Our initial plan was to basically sign with one bank partner and scale initially with them. And that's needed. A side note is that it's needed to stand up a company like you need because we don't make the financial services. If you're opening a checking account invoice to go or AngelList or any other customer, you're not actually opening an account with us.

You're opening an account on our stack delivered by this bank partner. So they're necessary for the creation of accounts, for money, movement, et cetera. So we had to get one of them at least. And so I met 50 banks. I probably traveled to meet 10 of them in different parts of the country. It was fun to just meet all sorts of people in different states. And we ended up really zooming in on one relationship that seemed to be the right one for us. And then Covid hit, and it was in March of 2020. The world of course, screeched to a halt, and the banks were no exception. There were specific reasons to be distracted if you're a bank. I mean, wasn't only the general distraction that all of us experienced. It's also the fact that banks had real concerns about their financial stability, the economy as a whole.

And of course there was a program called PPP, which allowed banks to extend capital, emergency capital, the small businesses. And every opportunistic business person, I think at the time in banks thought that it was a great way to bolster the balance sheet and then become more successful. And so banks got completely distracted. Their leadership teams were not in that place, and the interest rates dropped and dropping interest rate environment banks have less of an opportunity in this space. And so there was a perfect storm there that basically caused all of our bank conversations to slow down and freeze.

That was very, very concerning for us because you can imagine, I mean the difference between Unit launching in 2020, which we just did, and Unit launching a year later could have been one bank partner getting derailed and focusing on something else. So we learned how delicate those relationships were, and we decided that we are going to work with two partner banks. And I basically opened a much larger set of conversations and we ended up signing two and launching with two at the end of 2020.

Turner Novak:

And then you've got the partner banks launched. How long did it take then to build everything you needed, get a customer, a paying customer? How did that go?

Itai Damti:

That was a journey. So it wasn't that getting bank partners was the end of the journey. There was a lot of build out that needed to happen back then. We hired amazing people to join our team. It was the time to do it. One was an operations expert and one is our chief compliance officer, Amanda Swarberland.

Turner Novak:

Those were the first two hires?

Itai Damti:

Two people, yeah. So we had one more engineer in Israel, and Daron was building V-One of the software. But I worked really hard on these two hires, especially Amanda. She was one of the executives at Sunrise Banks. She managed the whole risk and compliance team of 40 plus people. And she was really one of the people that I met trying to impress and trying to lend as potential partners. And then we connected offline and she was able to see that what Unit was building was actually what she thought needed to exist in this industry.

So she joined Unit. It was, again, Covid create some sticking points there, but we crossed the bridge and eventually she joined. And so working towards launch was basically stand up what makes us a strong operating system for the bank as far as oversight, identity solutions, and the actual money movement rails and the safety and security as well as writing all the protocols, the procedures that allow us to be an effective partner to the bank.

And so all of this came to conclusion at the end of 2020. And then our first customers, I started speaking to companies when we had one ugly landing page that had one sentence in it, Unit is launching soon, and we do this and that. And people contacted me and I managed probably 20 sales conversations back then. And the first customer we signed was a YC company called Benepass that built HSA accounts or health savings accounts for individuals. They build benefit solutions, but they needed something that helps them park money on your name and make healthcare expenses in a compliant way. So we built what they needed, which was not a big departure from just a checking account. And we got them live in late 2020.

Turner Novak:

So you did that in 2020?

Itai Damti:

We signed them in late 2020, and I think they launched either end of the year or early the following year.

Turner Novak:

How easy was it, those customer conversations, it's a pretty complicated space and product that you're operating in. How did you convince people? How did those conversations go?

Itai Damti:

I don't take it for granted that anyone related to what we had to sell because it was obvious people had solutions outside of Unit. Our pitch was simplicity. The wedge was simplicity, and I think younger companies allow themselves to take a bet if they need something done in two months and they found a partner that seems to be credible and seems to be able to get them there, in many cases they would choose us. So ICE closed the first 50 deals in the company. It required a year plus of active selling and a lot of learning, but convincing them was mostly an act of celebrating the simplicity and of course getting the bank partners to meet them and getting excited about supporting them.

We sold simplicity from day one. We continue to sell simplicity, but back then it resonated with small companies. I think the journey that was non-obvious for us was how do you take that first set of young customers and go upmarket? How do you start impressing bigger and bigger companies who might need different endorsements and social proof and security protocols and certifications and more control over the product? And I think that the harder journey is really to start with this small customer base of small companies and really become more diversified and even serve public companies like we did today. But it had to start with small companies because frankly no one else would buy what we had to sell at the time when incumbents were in the market.

Turner Novak:

So you talked about you've closed 50 of the first customers. What was, I guess maybe switching to maybe more of lessons and things that you've learned over time, what are some of the big lessons you've learned from some of the prior companies and that you've built and then how's that informed all the things that you're doing now at Unit?

Itai Damti:

It's a big one. So I had two companies before Unit. One was that decade long journey with Daron and other two co-founders at Leverett.

Turner Novak:

What was that by the way?

Itai Damti:

So previous company, that company was still around is a brokerage infrastructure company. So if you want to start a Robinhood or Schwab anywhere in the world, you would come to us with a license and we'd give you all of the tech you need to run that business, including liquidity, risk management, trading platforms in 20 something languages, compliance tools, CRM. So it's really a vertical operating system for online brokers end to end.

But that required of course, extensive experience in trading and over time we just had to learn all of that from scratch. So that company was four founders, completely clueless, fresh off the Israeli Army as engineers. And we raised 120,000 I think effectively. So we did not really raise VC money and we grew that business organically to 160 people in six offices worldwide. And over the years I was leading engineering first and then I moved the product, I started and managed the product team and then I moved to Hong Kong to be heading CEO or be the CEO for Asia Pacific, so oversee the business side.

Which was a very interesting transition for me. I mean, just really crossing the lines to the dark side of business was a fun experience.

Turner Novak:

The dark side.

Itai Damti:

Yeah, technical people have a certain charm and you have to be almost naive to build and do it well. And in business it's a lot more unpredictable and you just have to navigate people in relationships and more obscure problems. So that was the first company. The second company was shortly collaborated with a friend in Hong Kong and we stood up a quant trading firm or quant trading desk that was trading between crypto exchanges in 2018. It was a bad year for crypto, but we did not take any directional bets on the market. We just did arbitrage and market making between different exchanges that business started to pick up but not at the speed that was satisfying or impressive.

And also I think I had a big learning about founder superpowers that I took away from that, which is it really takes two very specific people to build a quant firm. One is a world-class trader and one is a world-class techie. And Daron for example, is a world-class techie. I was not, and my co-founder was not and we were not traders. So it was a very interesting intellectual problem and I really enjoyed the mind games of capital markets and trading, but I realized that this is not where I'm going to shine. So that's the main learning from that second company. The first company, that decade long journey, I would say that we had two learnings that we reflected on in the early days of Unit. One is that it really sucks to build in a limited market. If you don't see your market as expanding and you're building for a small total addressable market, it's really hard to build big companies and enjoy the journey.

Those 10 years were a grind. We got the company to certain revenues and volume. We processed 200 billion a month when I left, but we still don't see it as our magnum opus. We don't see it as the one thing, our life's work because it was kept in ambition and frankly capital as well. So it was a bit hard to grow. And so building in a big market to us is a very, very important thing that we had to squint and realize that we had to squint and realize that we had to squint and realize that we had to squint and realize how the market might get bigger. But at Unit we did not want to be kept. The second thing is culture. We really thought how can we make things different this time? Life is too short to build in mediocre environments or build something you don't enjoy doing, especially as a second time founder.

And I think one of our learnings was that the culture that we've created at our first company, Leverett, was a result of directly projecting from the four founders onto the rest of the company. We're all strong personalities so it worked to 80, maybe a hundred people, but there was no top-down cultural sentiment in the company. It was just do do do, which is an important part of building. But it was very organic and I think at Unit we had to sit down and really articulate what drives us in terms of culture, values, execution, style, and hire accordingly.

Turner Novak:

Can you maybe explain how I should do that? If I'm a founder listening to this, how do I intentionally set my culture? That just sounds like a vague abstract concept.

Itai Damti:

It's one of these elusive terms like who defined French culture? Nobody had a top-down mandate to direct and articulate what French culture is, and yet when you go to France and you spend time with French people, you know what it means. So I think culture is one of these elusive terms that it has the meaning of whatever is in the field, not what has been dictated top to bottom. And I think that it makes it especially hard to define, but at Unit one of the main values we set for the company, which companies call this by different names, Stripe calls these principles, we call them values, we might change to call them principles as well. But what defines your execution style, urgency is one that we feel very strongly about. Wanting to make progress and wanting to understand what makes progress and pushing our team to achieve that.

Progress could mean launch V-One of Unit. It could mean launch a new product within Unit. It could mean improve the financial profile of Unit as a business and make the investments and milestones that get you there. So have this drive to... We want people to have this drive to constantly make impact and act with urgency. The second thing is precision. We said precision is the main value of the company and Daron and I have this shared brain of what precision means, but I have to try to articulate it to other people. And I think my main way to explain it to people is iterative mindset and always starting with the most important. So precision to me is if you want to launch a new website, there are many, many teams in the world that would lean towards what we call big bank projects, the perfect website, the most extensive website.

And then these projects become big bank projects where you sit on them and innovation looks like a step function where nothing gets delivered for nine months and then something gets delivered and it's big. That shape of innovation that moves in steps is not one that we like because we believe in a more iterative thing or iterative mindset that starts with the most important thing. So the way we would build a website would be what are the one or two pages that must exist today and how can we urge ourselves to launch them. Maybe with some line of thinking to the next pages, but what is the core of what we're trying to build and launch and then do it this week or next week and then get to the next layer and just do it in a repetitive iterative mindset.

So it's really the question of how do you force people to move in really small increments, what we call atomic projects, not big bank projects that are too big and how do you teach them to choose the most important next step or the most important atomic progress and not get distracted with nice to hips. So I think precision is really this to me, and I think it's very intuitive for people who develop software that software should be built in this type of mindset.

The Agile Manifesto was all about how do you make teams ship software in small and frequent increments and how do you make every increment the most important Next thing you can do, it's a very intuitive thing in the software world, but when you build a sales team or a marketing team or a compliance team or legal team or finance team, this iterative mindset that always looks at the next best action is really not there. And I think there is a tendency to go for big bank projects. We're just trying to be very, very ruthless about it and always coach people to be more precise.

Turner Novak:

So move quickly with intention on the incremental things that actually matter?

Itai Damti:

Exactly. Think about your job like a software engineer or like a product manager. Your job as a finance professional at Unit is a product. You're building that V six or V seven of the spreadsheet. You're shipping a new audit report, which by nature might be a big bank project, but how do you think about your job as a product that gets better and better over time and how do you always choose the right next step? I think is something that many people outside of building functions don't always internalize. And I think your company can move a lot faster if you just teach every person in the company to think in this mindset.

Hiring is another example. If we had no process for hiring or no set of interview questions for candidates, one version of solving it is coming up with a perfect set of questions and soliciting feedback from different parts of the company, from founders, from different existing employees and having that perfect set and launching it three months later. My version of making progress is choosing the one question that you wish to ask everyone starting today, ship it, make it part of the process and then add a second question the next day or next week.

But don't wait, don't wait for the perfect process because there is no perfect process and people put work in progress next to work at Unit sometimes on documents or deck. And I'm telling them everything is work in progress. If you put work in progress, you're almost apologizing for shipping something that's incomplete and we need to get rid of this sentiment. Everything you're shipping is valuable. Good job for shipping it. What's the next version?

Turner Novak:

So you have this other really interesting saying that I've heard you say, "Growth feels like failure." Maybe it's related, maybe it's not, but can you just explain what that is and if I'm a founder or anyone, just how do I internalize that and live with that mindset?

Itai Damti:

Yeah, I think lack of growth feels like a failure in a startup and also growth. So every startup feels like constant failure. Elon Musk said at some point that being a founder is staring into the abyss eating glass all the time. And I think it's very, very true. Like you see the potential risks for the company at all times, but you also have this special filter that only makes you see big problems that no one else is capable of handling.

By definition, that's your job as a founder as a CEO. So I think when the company grows, all these problems come your way, problems with customers, problems with partners, problems with employees, and it feels like things are breaking at the seams and growth feels like this constant state of failure where by definition you have to do a hundred things, but you have to choose the five that you're going to solve for this week.

So the demands on your time are always going to be bigger than your actual ability to invest time. And I think this is where the topic of precision comes in. If you live with this precision value in mind, you are going to influence the right set of things. You're going to choose the right set of things this week and you're going to make the investments small and manageable enough to put out the fires so that you can handle other fires next week.

And I think you also have to accept, I think one thing that really liberated me when I heard it from people was that as a founder you have to allow some amount of fires to burn at every given moment. Fires have to be manageable and cannot be existential to the company, but by definition your time is very limited. The demands on your time are infinitely scalable and almost unlimited and you have to accept that you're only going to influence a small set of things every week. And so being precise is choosing those things carefully and choosing the actions carefully.

Turner Novak:

What is an example maybe of a small fire that you can let burn and then maybe just a crazy fire the house is burning down, you got to put it out immediately. Can you give us an example of both?

Itai Damti:

Yeah, I mean small fire would be something like you don't yet have a leveling system in a 60 person company. So to be very organized with talent development and making sure that people feel good in their jobs and have a promotional promotion horizon companies put in place leveling systems and it's tested and true and it's a best practice. You feel the pressure to do it at 60, there is no doubt that some amount of employees are managers in the company are going to feel that things are not just right and there's going to be pressure on you to address it.

And if you have the leader to do it and this is the best use of their time, I encourage you to do it. But it's 60 people, I would encourage you to look at other things. It might not be working. For example, while it builds all of these people function in-house or people processes in-house, your go-to-market team can be mis performing or underperforming if you're not there to debug the problems, to me this is a problem that can compound and problems can come in many forms.

It can be leadership issues, it can be process issues, it can be expectation setting and ambition. And I think that there are problems that you can look away from for some time, like the leveling example that I gave. And there are problems that you have to deal with today because they're existential or there's something that could be just bigger in magnitude.

So I just think about it as red, yellow, green, what's your founder scorecard for the company and which areas are yellow or red that might have to be better? And I encourage people to spend time there. Stuff that can't wait is production issues that might be chronic, teams that are critical to the company that are not delivering at the right set of ambition and pace. It could be that you have some cultural issue that you must attend to.

It could be that a key partnership or key customer or maybe a key sales process that gets your company to the next level is important. I found that Unit may be the most unexpected category of things that I had to put my time into is launching a new product. We have this core of Unit, we have the dashboard, the API, the white-label interfaces, and introducing something like lending into the equation or financial accounts, which is a special type of account that we're envisioning now or even our white-label app, which we shipped recently. It sounds like incremental innovation, but Unit is at the size now where getting those products to production, having clients use them in the wild takes monumental effort.

And as a founder you take it for granted that if you appoint someone and you let them do the cross-functional work that gets you to launch and sign customers, things will take care of themselves. But I found that this is the one thing that I can't ignore. I can't just delegate launching new products in a complex environment. I have to be there. I have to set the ambition and I have to be a forcing function for the actual delivery. So that's like a benign version of something you have to attend to. There are many burning fires that you have to attend to every day. And I mentioned some other types.

Turner Novak:

Unpacking some of what you said, if it ties to increasing the cash flow of the business, whether it's revenue costs, expenses, something that's existential, decreasing, the burn rate, increasing profitability, something like that. Is that a good way to think about it?

Itai Damti:

Yeah, I think about the job of a founder, or at least from my point of view is increasing. So making the company live longer and eventually reach profitability. That's the big problem statement. The way in which you can do it is either by increasing revenues or by increasing or improving the financial profile of the company. So that's a set of problems that I consider very, very important.

I attended to five or six renewal processes with our vendors recently that had big financial implications for the company. So that's one great example. Another one is revenue growth. So in standing up a go-to-market organization, empowering them to grow, you need to monitor them and make sure that the growth trajectory that you have as a company is being met. And many things will go wrong as you try to scale from 1 million to 5 million, from five to 15 and from 15 to a 100.

And we're now at the latter of these scenarios, but there's always stuff that can go wrong and being with your eyes on the problem is very important. The other thing that exists in our industry is there are defensibility and security and reputational risks that companies have when they deal with sensitive matters. And so I think one of our biggest missions is to stand up an organizational unit that can support our partner banks in delivering these services in a safe and compliant way. There's a lot of downside to these products if they're not delivered in a safe and compliant way.

We invest many, many millions a year in making sure that banks get oversight capabilities that make them stand out, that they can see all of the activity on the platform and can monitor anything that makes them suspect or ask questions. And this is a regulatory expectation at this point. So it might not fall in the category of financial risks of the company, but the downside risks, especially in places like FinTech, need to be managed at all times. And to me it's the stuff that goes under the water in the iceberg. If you go to the Unit website, you see just one tip of what we do as a company that meets the demand, but there's so much that happens behind the scenes.

Turner Novak:

And it really does tie into the revenue and the financial profile of the business because if you're not compliant, you're not doing something that's regulatorily sound. I'm not sure if that's a word. I mean there's no business. You can't generate revenue.

Itai Damti:

Exactly. And there's also between the way in which you operate and the long-term application. So it could seem like you're making good strides if you're signing a bunch of crypto companies in 2020 or 2021 and your investors give you some praise. But then if those companies are not financially stable or they might be risking for your partner banks, those revenues are low quality revenue. So our philosophy has been to grow slower intentionally because growing too fast in this space can also be something that creates risks. So there are many, many trade-offs and there are things you just have to attend to because they're existential the business.

Turner Novak:

Another question that I got from Nick at This Week in Fintech, he was curious about just a question about crypto and how it maybe intersects with financial system with Unit. I completely agree with your point about revenue quality or quality of the revenue brought in from certain customers. I've thought about that a lot specifically with crypto in 21 was very, very slow to invest there. How did you think about crypto just as a business and what products you were building for it?

Itai Damti:

We're not. So if you look at what our personal interests are, Daron and I both got into the Bitcoin invention back in 2013. We geeked out about it. I gave a lecture on Bitcoin in 2014 in our previous company and I was definitely interested in it intellectually and what it represented in terms of decentralized money but Unit had absolutely zero involvement with crypto. And look, crypto is a form of programming value that is a kin to what we do as a company, but we prefer to solve the harder problem of programming dollars when they need to be programmed, when there is value in programming them as opposed to programming entirely new constructs and forms of value. Because I just believe that 99.999% of the individuals and businesses in the world want to interact with smart money, that is their current money and that's what we're trying to solve.

I think it's easy in a way to focus on crypto because the regulatory oversight in that part of the ecosystem is very, very small. Eventually you're talking about decentralized systems that don't have government controls over them. So it might be tempting for people to erase what we have in our current money ecosystem and go build on entirely new rails. I just like the harder and meatier and more valuable problems. And I think programming money, real money is a very, very hard problem to solve from a regulatory perspective. From a compliance perspective, again, the bank facing aspect of all of this is extremely critical. And of course delivering it in a way that's intuitive and simple is something that we always try to do.

Turner Novak:

Is there any more really big outstanding problems in financial services, money movement, banking, however you want to define it, that still exists that people maybe don't know about because we're removed from it?

Itai Damti:

So I do think that the introduction of the Shopify or the AngelList or the invoice to go that company that delivers financial services, but it's not a financial institution. It seems like an innocent change in the supply chain. Just one person between or one entity between the bank and the end user. But in reality and regulators know it well, this addition creates a whole new set of service areas in risk and compliance because when you walk into a bank, the teller that's opening an account for you, if that's what you're doing, is trained in using compliant language and serving you and disclosing and giving you agreements that the bank crafted and they know you're a real person. So the fraud and synthetic identity element is then eliminated. So there's this old school environment that banks were built in and inserting just one entity between the end user and the bank is creating these new surface areas.

I would say one of the poorly understood concepts in FinTech is just how complex it has been for banks to oversee how those tech companies behave in reality. So when I spoke to 50 banks in the process of starting Unit and I asked them, "How many FinTech partnerships do you have?" They said 50. Some of them said 50 because they've been in business for years. And when I asked them, "What are the mechanics, what is your team actually seeing about their activity in real time, about the end customers, about the fees they charge about the marketing materials?" The banks always had a very manual and very low tooling answer to this question. Those companies, if you have 50 partnerships, each one of them has maybe 13 surface areas like money laundering and identification and fraud and statements and call it 13. It's about 650 surface areas that exist in your FinTech portfolio.