🎧🍌 How to Move Quadrillions of Dollars - The Story of Modern Treasury with Dimitri Dadiomov (Co-founder and CEO, Modern Treasury)

How to pick co-founders, why early customers deserve more credit, Dimitri's experience in YC, using PLG to build a deeper product, going slow to go fast, and an inside look at March's banking collapse

Stream on:

🍎 Apple

🎧 Spotify

📺 YouTube

This week’s guest on the podcast is Dimitri Dadiomov, Co-founder and CEO of Modern Treasury.

Find Dimitri on Twitter and LinkedIn

Modern Treasury is building software for a new era of payments. What exactly does that mean? Accounting is entirely rules-based and the global banking system moves quadrillions of dollars per year (not a typo), yet most accounting and money movement is still manual and requires large teams at scale. Modern Treasury builds software for those teams.

Dimitri and his co-founders Matt and Sam started the company in 2018, and have since raised over $183 million, supported by investors like YCombinator, Benchmark, Altimeter, Salesforce Ventures, Quiet Capital, WndrCo, TQ Ventures, and Edward Lando.

The episode is brought to you by Secureframe

Secureframe is the automated compliance platform built by compliance experts.

Thousands of customers like Ramp, AngelList, and Coda trust Secureframe to get and stay compliant with security and privacy frameworks like SOC 2, ISO 27001, HIPAA, PCI, GDPR, and more.

Use Secureframe to automate your compliance process, focus on your customers, and close deals + grow your revenue faster.

In this episode, we discuss:

How the global banking system moves over $1 quadrillion per year

Why B2B products should be easy to use with broad use cases

What makes a good API business

Why the YC application is a great forcing function for founders

How to pick your co-founders

Modern Treasury’s YC experience

Never pivoting despite taking six months to get the first customer

Why the first customers of a B2B business should get more credit

How PLG helps build a better product

Finding holes in the market for an initial go-to-market strategy

The depth of Modern Treasury’s product

Why they should have built a sales team sooner

How deep, broad customer relationships helped raise a Series A from Benchmark

Why it’s important to go slow to go fast

How Dimitri sets an intentional culture around studying other businesses

When distribution can be more important than product

What happened inside Modern Treasury during the collapse of SVB and Signature Bank

Why Dimitri sends Saturday update emails to entire company

The founders Dimitri really admires

🙏 Thanks to Zac and Xavier at Supermix helping with production and distribution!

To inquire on sponsorship opportunities for future episodes, click here.

Transcript

Find transcripts of all prior episodes here.

Turner: I thought we could kick things off. You guys are in this really interesting market called payment operations. That's how you started the company. Can you explain what that means and why it was worth building a company around?

Dimitri: Yeah, totally. Before we talk about payment operations, I gotta tell you, when you invited me to this podcast, I went and I bought this amazing hoodie with bananas all over it. But unfortunately it wasn't shipped here in time, so I'm very sad that we're doing this and I'm not wearing the banana hoodie.

Turner: We'll do another episode in a couple months.

Dimitri: Sounds good. So payment operations – what Modern Treasury does is build software that is aimed to be the operating system for money movement. So companies that move money and connect to banks, ledger things and keep track of and reconcile everything that happens in their business.

We hope to build the best software for that. That is something that we saw up close and personal, and we can talk about that. But it's a problem that exists in a lot of different companies and the context is almost definitionally for businesses where there's some money moving.

Specifically, certain types of businesses who are in the flow of funds or they're somehow moving funds through their marketplace or through their financial services offering – they have this problem in a significantly more complicated way than the majority of businesses. And so, when you get to higher volumes, you get to higher precision, you get to more errors. It becomes something that you really need software for.

Traditionally, a lot of it has been built internally or has been solved with operations teams that are doing things by hand. Modern Treasury is trying to help build software for this to make it much easier and simpler to start businesses in those industries.

Turner: When you say “doing it by hand,” that means probably a bunch of spreadsheets and emails and setting up bank wires manually, things like that?

Dimitri: Absolutely. You can just think about it from a capital call venture investing flow perspective, right? Like you log into bank portals, you refresh things, you mark it as complete, you wait for the wire to show up. If you're doing it for one or two, it's not a big deal.

But if you're doing it for a thousand a day, you really can't do this by hand anymore. Or maybe you can, but you have to hire a large team to do it, and it's not gonna be perfect. And so that's where those types of problems arrive.

Turner: I think you gave an example once of Airbnb where, in theory, you just think, “Oh, there's some people staying at houses – it's just the consumer side,” but internally there's a lot that also goes on too. They're moving money between all of their different counterparties too. Right?

Dimitri: Oh, for sure. It's hundreds of people at Airbnb that are occupied every day, building things around this, right? So think of every time somebody goes from the US to France and somebody stays with a host in France, you have to basically think through the payments on both sides.

How do you actually move money? How do you think about a foreign exchange? When do you actually move it? When do you release the funds? What if there's an error? Does it bounce? And is there a problem?

And when the host inevitably calls the customer service line and says, “I've got this problem, I can't see the funds.” What is the customer service agent looking at to ascertain whether that's a real problem or not? There's all sorts of problems that show up and you have to go solve it within different teams inside the company.

For example, how does the engineering team handle this? How does the product team deal with this? How does customer service or how does finance and accounting deal with this? There are lots of different places where these problems pop up.

Turner: There's probably – at least from some of the larger corporations I've worked at, which weren't even that big – tens or hundreds of different bank accounts too. And then there's a bunch of different spreadsheets for each. Each customer might have a spreadsheet or each division or country or segment. Or all of those different segments in each country have their own – so pretty complicated.

Dimitri: There's somebody somewhere that knows exactly how those spreadsheets are operated. And if you lose that person, now the whole company doesn't know it anymore because it's saved in Excel 2013 in a file on somebody's computer.

Turner: You've probably seen that one meme recently where it's like a crab holding something up and it's Microsoft Excel and the World Financial System. Have you seen that one?

Dimitri: Yeah, for sure. It's true. People talk about how “Microsoft is not a fintech company.” I don't know about that – the entire financial system runs on Excel.

Turner: Yeah. It's pretty crazy how under-monetized Excel is because you pay probably 10, 20, or 30 bucks a month – whatever the number is per user. But it's supporting the backend, or was historically, for a lot of businesses. It's wild.

Dimitri: Totally. And Excel is such an amazing product because you can use it for a to-do list or you can use it to build the most complicated macro with 47 tabs and you know, running all the way through probably 2500 if you really wanted to – and people do. So it's pretty amazing.

I think good products, especially good B2B products should aspire to have this range of use cases where somebody who's a total noob can start using it without a whole lot of explanation. And I think that's a really good thing.

But also you can become a master of it, right? Like when people get certifications in certain types of software, in a way it's like, well maybe your software's so complicated, you now need to go to school to be able to do this. But on the other, there is that complexity that this product actually can do so much that's different.

Turner: Yeah, I think I've seen numbers thrown around – the total money moved, the volume is (throwing out a fake number) ~$750 trillion a year. It's like quadrillions of dollars. And obviously a company that does a billion dollars in revenue might be moving a couple billion, in all these different transactions.

So when you think about the scale, it's probably one of the biggest. I don't know how you actually size the market in terms of what revenue gets generated from that, but just the size of the transactions happening are astronomical.

Dimitri: Money moved is not necessarily revenue to the company. So if you think about a payroll company, the payroll company moves a lot of money. All the salaries get moved maybe twice from the company to the payroll company and then from the payroll company's accounts to the tax agencies and benefits accounts and the employees and everything.

That's a perfect example where that company moves orders of magnitude more dollars than their revenue. But it's a daily problem for them.

Turner: It costs money to support money movement, right? Like you said, you generally need a team. The bigger you get, the more money you're moving. You might have hundreds of people, which gets pretty expensive.

Dimitri: This is something that you realize once you are in any industry for a while. You get better with scale and with seeing more versions of it. I think this is one of these things that historically has been a really problematic thing for web companies.

This is something that we saw at LendingHome[1] so we were working on this website that talked to the financial system in a mortgage context. We were funding wires to fund mortgages. We were collecting ACHs every month to bring in the repayments, and we had to build this whole thing from scratch, which was connected to the bank that we were working with. And it was really hard.

I remember one of the things that's set us down the Modern Treasury path has really been that we realized there was this horizontal problem that existed across a lot of different websites and companies, which also really matters.

If you actually think about what has been going on in the web and innovation world, there are all these startups that have been going after things that, initially when the web started, were around paying and buying something with a credit card from a checkout page.

[1] Dmitri was a Principal Product Manager at LendingHome (now called Kiavi) before starting Modern Treasury.

Turner: So these are all consumer solutions essentially?

Dimitri: Right. It was basically things like travel, right? Expedia started with travel and Amazon started with buying a book for $30 bucks or something. Netflix started with entertainment. Those types of things are $20-100 transactions, which is probably their average transaction.

You do that over a credit card and it was painful at the time, right? If you go back to the late 90s, early 2000s, all these companies have to figure that out by themselves and figure out how to build it. And obviously there's companies like Adyen and Braintree and Stripe that have now been built to solve that problem.

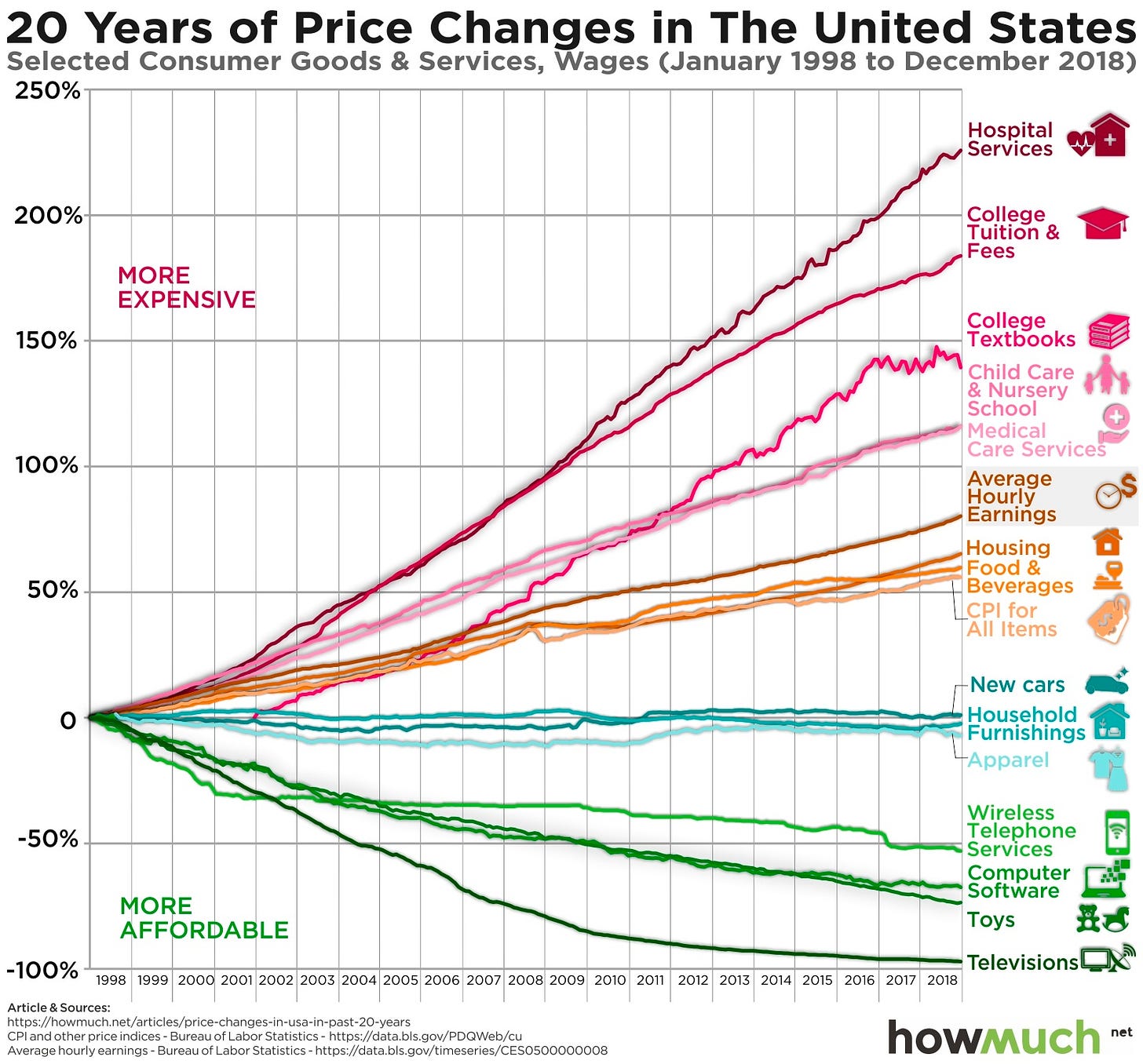

So you don't have this problem with credit cards. I'm sure you've probably seen those charts where the level of inflation in those consumer goods has come down, right? Basically those things such as buying a TV or going on a trip have become cheaper over time and the things that have gotten more expensive are the things that you pay for using wire and check. So they are healthcare, education, real estate, housing, financial services, things that as a society we really care about.

Price changes over time. Source.

I remember one of the things that we realized when we were working on this problem regarding mortgages at LendingHome was, “We know how to solve this problem.” And a lot of companies should be built to fix the problems that exist in all these sectors just mentioned, but there's this giant boulder.

If you think about this highway, there's a giant boulder that sends traffic the other way because it's just hard to get started. And there's an additional tax on getting started – you don't have a way to connect to the banking system. You don't have a payment operations software product that exists that makes it easy for these companies to get going.

So we thought, “Hey, we have an obligation to go build this because actually it is gonna enable all these companies to innovate in housing costs and how payroll runs and how people get healthcare.” That's a really cool aspect of Modern Treasury – we help enable companies to do the things that society really cares about, and they go build web startups.

We as founders, we all love web startups. A good startup story is an amazing thing. And there's just not enough of those in some of these areas that I just mentioned. So anyway, that's a longer answer than maybe you wanted, but, that's something that we felt we should just go fix because somebody has to and nobody has. And it's going to be taxing on all the founders who want to try to build companies in those areas.

Turner: Yeah, and you fixed it, or you built some solutions inside of LendingHome, or at least got super familiar with them, right?

Dimitri: Yeah. We had to go build it from scratch, but we got familiar with the problem set for sure.

Turner: And it was really interesting. There's three co-founders at Modern Treasury, you, Matt, and Sam, you all started on the exact same day, right?

Dimitri: Yeah, we started the same day. It was a little bit coordinated between Sam and I. So Sam and I joined to start a new product, and it was something that the founders of LendingHome wanted to build as part of the PowerPoint when they were pitching the company, but they never got around to building it.

The company was probably about 75 people at the time. Sam and I joined, on the same day, by design, because we were starting this retail investing part of the product. LendingHome was originating mortgages. They were funding these fix-and-flip loans to people who were buying a property, renovating it, and selling it after 6 or 12 months. They're still one of the largest dominant players in that market.

I should mention LendingHome rebranded as Kiavi. So it's known as Kiavi now. But back then, one of the ways in which these loans would then get sold to investors was in spreadsheets to large portfolios of investors, hedge funds, and the like.

There was this idea of letting individuals go and invest. Think AngelList style – how do you actually fractionalize and allow people, individuals, to invest in a smaller fraction and build a portfolio of these properties and loans, etc. So that was what we had started.

Sam and I built this website. It was basically an e-commerce shopping cart that allowed people to log in and buy a $1000 or $5000 or some small percentage of a mortgage, which is usually $300k, $500k, $1 million. But the thing is these are all fix-and-flip properties. So every one of these properties has water damage or a bad kitchen or there's some problem with it.

When we built the website, we jokingly would call it Ugly Airbnb. You log into Airbnb, and instead of it being like this amazing photo, it's more like, “Look, there was a very, very small fire and we can cover it up really quickly and add a lot of value and sell it,” you know? So that was the retail investing product.

From a money movement perspective, as soon as we fractionalized the loan – think about how you own $2,000 of this $200,000 mortgage – so now 1% of every payment that comes back once a month in the first of the month, we now have to do this fraction math from like sixth grade and say, oh, well two over 200 times $3,000 payment… you now have to move that money into your account. You have a wallet. And then you can decide if you wanna reinvest it or you want to withdraw it.

It very quickly – just the number of transactions – ballooned and we had people coming to us from finance and accounting and other capital markets, other parts saying like, “What is this payment? What happened?” Highlighting a statement in yellow. That was the beginning of us getting obsessed with these problems of: how do you do this in a simple way?

Turner: And this was like a B2B type product or solution. But you were almost dealing with the consumer level payments, where it was, one loan, there were a hundred individuals that are 1%. There were hundreds of these loans. You have thousands, tens of thousands of like $100, $300 wires.

Dimitri: Yeah, we were doing, I want to say, about 70,000 transactions a month, when we left. So, you know, that's a lot. That's a long statement.

Turner: Yeah. And so an interesting question that I'm wondering is how did you know that all three of you as co-founders, that you worked well together and that you wanted to take this journey? Because obviously you just told us how you came up with the idea, but how did you decide these were the right people to go on this journey with?

Dimitri: Yeah, it's a good question. It was an emerging thing. I mean we worked together for three years. Sam and I literally worked together every single day for those three years, like we were working on the same project. Matt was working on more of the borrower-facing piece of LendingHome.

So he was around but wasn't working very closely in the same way. But we became very good friends and we'd go skiing together and so on. So I think it was a combination of, seeing the problem, realizing how it's something that we wanted to work on.

And then I think feeling like these are people I would be excited to work with every day for what could be a very long time. I think that's how it was for me. And then of course there's complementary skill sets as well.

I was a product manager, and Sam and Matt were engineers. Sam was working more on the backend and the bank integration pieces although he is incredibly talented across the board.

And then Matt was working more on the front end piece and so, Matt is our Chief Product Officer. Now he is more focused on product than on writing code. But, you know, in the early days he wrote a lot of code in the first, I don't know, 18 months, or I think for a while he was still the number one person by lines of code submitted, and I think he just recently lost that.

So that was something that we all felt like it worked well. We saw the problem together. We wanted to work together and it was just easy.

Turner: And then, so I think you said you were there for about three years and then I think it was Sam who said that it was January of 2018. He came to you with a crazy idea. He wanted to start a bank. What was your reaction?

Dimitri: I was not very interested.

Turner: Why not?

Dimitri: It just sounds hard and it doesn't sound like something we know anything about. I think I have a lot of respect for banks. That maybe sounds weird for a fintech founder to say, but I just think banking is a very complicated business. It's a very large business.

There are 3000 banks in the US, and all of them, while it's easy for tech people to say, “Oh, they're all the same, like a wire and a loan”, that's actually not true at all. When you look at every one of those banks, they have some strategy around it of who they want to go after, who they want to be the best customer for.

Maybe it's geographic, maybe it's a a segment. Maybe it's an industry. You know, we can talk about that, but it's very hard. Even Bank of America, the dominant banks, they don't have that big of a market share in most of these. And I think the reason for it is because it's just such a big industry and it's hard to do well. So the idea of starting a bank, obviously people have done it, and it's fascinating to watch and some of them will succeed.

But I just didn't have a lot of interest in that. I think that it has a very heavy regulatory burden. You have to think about hiring a lot of compliance officers and lawyers. What I thought we knew was the tech part of it. So I remember my reaction was like, “No, I don't want to do that.”

“But let's just entertain you for a second, Sam. If you had a bank, what even compels you to say that? Like what is the problem you're trying to solve?” And we started digging in and a lot of it was focused around API access and how do you get developers and product people to be able to connect to banking services in a better way, which is an infinitesimally thin part of what a bank is.

I told them, “Well, why don't we maybe build that as a product. Like, let's dig into that and think about that.” And then you realize, “Oh, wait a second, most companies of any scale actually work across different banks.”

So even if you solve it as a single bank, it doesn't actually solve the problem. The CFO and the CTO of that company have a problem, which is, how do I connect to my seven banks or to my 30 banks? And so any one of those banks having a better connectivity set doesn't solve the problem.

And I think this is something that is the power of being hyper-focused. As for us now as Modern Treasury, we are a software company. We have zero ambition to be a bank. From the very beginning, that's been true. And we have zero ambition to somehow focus on a certain industry or something like that.

We want to be this general infrastructure software product. And going back to the conversation we were having earlier about Excel, like I admire that about Excel that people use it for very different use cases.

So my reaction to Sam was, “No, you don't know anything about starting a bank. I certainly don't know anything about starting a bank.” I don't want to speak for Sam, but I don't really want to start a bank. “But what compels you to say that? And then let's isolate that and then try to figure out if that's a thing.”

And then, you very quickly realize there is a functionality product there that is missing. We would've bought it at LendingHome if we had it available to us in 2015. This was now 2018. We had built a small version of it in a situation where it's very hard to argue for resources because it's not your core product.

You’re basically saying, “No, we totally should not launch a new state and actually start selling to new attractive borrowers and do all the things that the business is actually doing. You know what we want to do? We really want to get really good at reconciliation of ACH.” That's never going to be the first board deck or product slide.

But it's really important, and it's core to the smooth operations of a company. So you actually have to do that. So anyway, that was the conversation that Sam and I were having, when he first came to me with this idea.

Turner: And so is that what makes a good API or maybe just like a broader software product where it just solves like a operational headache? That maybe saves you money or resources and allows you to focus on what you do well. Is that a way to think about it?

Dimitri: I think it's a great way to think about it. I think there's even a funny way to frame it, which is, if you can build software that can do a job, like an actual job – if you can find a job description that somebody's hiring for that says, “Do this for me,” then probably a lot of people will do that.

One of the things that we did early on as like a growth hack is searching for job descriptions that said the word ACH in them. Because ACH came up in the 1970s. Nobody's innovating at startup companies on ACH. If you say the word engineer in the heading and then say the word ACH somewhere in the body of the job description, what you're saying is you have to make an integration to an ACH connection.

That is a very good giveaway that you as a company have this issue or this problem that you want solved. You know, I think most people don't have a strong view on how to solve it. If there's a software product that does the job for you? Great, you do this.

And again, not to keep going back to Microsoft analogies, but you don't have people who are typing things for you anymore. Like you just have Microsoft Word or Google Docs and you're set.

I think that's a good way to think about B2B companies or products – who would use it really? And what would they pay for it? And a job description tells you how much they would pay for it. And who would it be?

Turner: At what point did you guys apply to YC and go through YC? When did you decide like, “All right, LendingHome is great. We learned a lot. We're going to start this company.” Was there a moment?

Dimitri: We had a bunch of friends that we were just like talking to about this idea and just testing it. And some of them had been YC founders and they said, “Well, why don't you use the YC application as a forcing function to clarify your thinking.”

We definitely were getting a little bit more serious about doing this to the company, and I would encourage anybody who thinks about an idea to use the YC application – whether you apply or not, doesn't matter. The YC application itself is just a good forcing function of: can you distill this in a couple of sentences? Can you distill the customer types? Who would you sell to? What would you do if you had 90 days? What would you actually do to advance this idea forward? They're clarifying simple questions.

So anyway, we applied and I guess it was, would've been like April or something. This is 2018 and you know, we got an interview and we interviewed and we got it. And then, I mean it was very clear – like we just got more and more confidence as we went through the process because we met more companies that were smiling out and say “Oh yeah, I don't know if we'd be customers today because we're already built it, but boy do I wish we didn't have to.”

So we got to meet more and more people who gave us other ideas. You realize this is one of these problems that has different flavors to it. There's different, problems that come up as soon as you're doing payments at scale. And we had some of those at LendingHome, but LendingHome wasn't international, it was domestic only.

There was a certain set of problems that just didn't even exist. So anyway, we kept discovering new problems as we were going along and it just felt like such a rich area. Both in terms of impact and ability to help certain companies that we thought mattered, but also a rich area in terms of things to build and additional new products to add.

And, you know, I still feel this way today. It was giving us more and more confidence. And I think that if we'd gone through the process and we realized that it's actually smaller and less real than we thought, we maybe wouldn't have pursued it. But, as it unfolded, we realized, this is actually bigger than we thought. Not smaller.

Turner: And that's really interesting that you say that because I can't remember if it was Chris on your team or Sam who specifically mentioned it took you guys a while to sign your first customer. And with YC, like you said, 90 days, usually there’s a forcing function to build something people want and they start paying you for it. So what happened throughout YC? You never pivoted. Can you talk about that?

Dimitri: So we got into YC. We incorporated the company in I think May or June, and we started building. So on the one hand we had a good idea of what it was that we were trying to build.

We started working out of my apartment – Sam and Matt would come over every day and we would just basically be writing, writing code, writing our APIs, right? Starting the app, doing all the things that would be required to put an MVP in somebody's hands and actually have them use a product.

Simultaneously ,we did this exercise that I think is really useful to basically write down all the things that we needed to do as a founding team. And of the three of us, we put who was the owner of what – each one of them said, who's the primary, who's a secondary, and who doesn't matter.

We basically decided that this would help us move faster. So as an example, Sam and Matt, Sam was the CTO, he's the primary on all technical decisions. Matt was secondary and I didn't matter. So they could decide whether they wanted to work on AWS or Google Cloud without me having anything to add to that discussion.

One of the things that Sam and I were primary and secondary on is the bank side. And so we spent a lot of time on working with banks, getting to know banks, opening bank accounts, building our connectivity from our corporate account to this.

And that was really important for us to get to the point where we could feel like, okay, we actually like we've actually done the work. It's not like we're going to start doing this right after the contract was signed.

And then, Matt and I were working on a lot of the customer side, so we're talking to companies, understanding their problems, seeing where use cases were similar or different, and who's going to have the most pain and the most heat about this. And so we spent a lot of time talking to customers.

We had a lot of people who basically were smiling and nodding and saying, “This would totally be a thing that I would buy in some theoretical world where it was like four years ago, but no, I don't need it now.”

By the way, the other piece is that money movement is such a core piece of your business that it's hard to convince somebody to be the first customer of a startup. And I think that's true for all infrastructure companies. So you have to have a certain staying power to keep coming back and show a little bit more progress and convince people.

And like you mentioned, we were getting together in YC every week with our cohort of companies. And they all had a beautiful graph that went up into the right and it went from, 4 to 10 to 30 or whatever unit they were looking at. We were just like, “We opened another bank account.” And that doesn't sound like progress to most companies.

So we ended up going through demo day with no customers. We never got a customer doing YC. We raised our seed round. We didn't have a customer. We kept going.

It took us about three months after YC that a friend of mine, who I went to business school with, was starting a company that was in the healthcare space, and became our first customer, which we're very grateful for.

I think in B2B companies in particular, the founders get a lot of credit and the first investors get credit and actually it’s the first customers who put this whole castle in the air, into a real business. So the first customer is really, really important.

Sana Benefits, shout out to Will – they were our first customer. They're still a customer today. They've grown a lot. But it was a very good validation that we're able to get them up and running. With SVB as their first bank that we're supporting. and that was about six months after we started the company.

Turner: Interesting. And I think YC maybe suggested like, “Hey, do something else, is that true?”

Dimitri: Yeah. YC does that. Well, first of all, YC will probably suggest that to every company. I mean, YC is very good at pushing you a little bit on your beliefs or assumptions or try to understand how dedicated are you to this? Have you really thought through all the different elements?

So I think that's something that YC does in general for a lot of companies. But yeah, for sure, for us, I mean, it's like we would just show up and there's like zero apparent measures of success that we can point to. And so, you know, if you do that for a week or two or three, fine. But 12 weeks later – well, are you guys actually in a different place?

And we were like, “Yeah, we are totally in different place because we now have a product that works. We can show it moves money, we connect to the bank. All these things have to be true on the path to success.”

It was a longer thing to build, and even looking back now, six months isn't that crazy long of a time to start something that's fairly big and heavy. And a lot of it is because we already knew how this worked from having built something similar to LendingHomes. So it wasn't like we were discovering and understanding it from, from scratch.

We have this picture of Sam, when he got his 2018 NACHA manual. It's like this 600 page book that is just like all the different edge cases and things that you have to understand in order to know how this product works when we got our YC check. It was the first thing that we bought, and it showed up like three weeks later. And there's this picture of Sam, being super happy. Just immeasurably happy that he's got this manual.

But again, we needed to go through that in order to build the product that we then eventually deployed and sold.

Turner: Okay. And NACHA is the National ACH Association or something,

Dimitri: Automated clearing house. Yep.

Turner: “Money movement rules and that's probably the opportunity for the company,” is what Sam said. You guys basically codified the whole book. You took all these different rules and all these things that were outlined in there and basically built software that would just do it.

Dimitri: Yeah, and we translated a lot of these signals that were codified in the book, but they were not in a modern day API set. There weren't web hooks that would just notify you if something failed. And so basically what ended up happening was every one of these companies that had to go build to this, like had to build that from scratch.

And you discover one of the pain points is either you can read the book and you can actually discover every single edge case. So what happens if this payment gets disputed by the receiver. What happens if you ACH a dead person – that was like an early story that Matt Marcus put together. This post went to number one on Hacker News because it's just like one of these weirdly morbid things that people on Hacker News are going to be interested in. The intersection of morbid and nerdy is a good place to start.

But anyway all those types of things, a lot of times companies will build haphazardly and then they discover every one of those because there's like a ticket coming in from customer success being like, “This was a problem. A customer called and this is not working.” That's a bad customer experience. It's inefficient. Everybody's wasting time.

We codified all that and built it in a way that you can just deploy in a day and never think about it again. And so that is something that I think is pretty important. But yeah, that's where that book was really important for us to have early on.

Turner: I'm curious, and this is also a question from Chetan at Benchmark, one of your board members, he said we need to talk about just how deep you guys went, which we're in the middle of right now. How did the product evolve? Was it mostly customer feedback?

Dimitri: A lot of it was talking to customers and writing code. That's how products evolve. So we talked to a lot of customers and saw adjacent problems. So, that has been a lot of the evolution and the initials that we talked about.

It's this payment API that was codifying the different types of payments that a bank might have. That includes ACH, wires, and paper checks – more recently, RTP[2] and FedNow[3] are these real-time payment methods. It’s basically anything that the bank is going to offer programmatically to a company that does this at a bigger scale.

We wanted to have a good set of tools, and it's not just APIs. It's also things like, dev portals and logging and all the audits – like all the things that people might want to have as they actually deploy this and get up and running. So that was product number one.

Now, one way to think about this is: what other problems show up when you as a company start moving a lot of money? Well, the first one is pretty obvious, which is you should probably track it. You should probably track all these flows of funds that you're doing. And so that takes the form of ledgers.

Ledgers is our second product that was a standalone product. And it's really a database that helps with the tracking of a ledger. It could be money movement – that mostly is what it is – but you could use it for something like loyalty points, rewards points, things like that. But really it's like every time that money moves, you should really record it. You should keep track of it. You should have, an audit log of that.

We probably were like two years old when we started ledgers. We'd been thinking about it for a while, and we started feeling like, “Okay, that within a subset of our payments customers, there's a lot of people that need ledgers and really wish we had it already. And so we built it.

ClassPass was our first customer on ledgers, so they have 80,000 plus studios globally. Every time you go to a class at one of those studios, they decrement an account, balance increment a studio balance. There may or may not be a money movement actually associated without that moment, but you just track it.

[2] RTP stands for Real-Time Payments, which are payments made between bank accounts that are initiated, cleared and settled within seconds, at any time of the day or week, holidays and weekends included.

[3]FedNow is a new instant payment infrastructure developed by the Federal Reserve that allows financial institutions to enable businesses and individuals to send and receive instant payments in real time, around the clock, every day of the year.

Turner: Oh man, that sounds even more complicated. No money movement, but you still have to track.

Dimitri: Certainly, yeah. I mean, a lot of these closed loop systems – a lot of companies now are very focused on wallets and closed loop systems and things like that – and that is literally what a closed loop system is.

There's not the transfer that happens that everybody's aware of and can see in their account balance in whatever app, but it actually doesn't have a transfer in the US banking system. It's not one-to-one. And so maybe you're net settling it every once in a while. It gets really complicated.

Another common problem that you would have is, “Oh the bank is asking me for all this compliance stuff and I need to do KYC and KYB, and all these types of things.” So we added the capacity to add a counterparty to do the KYC piece, identity to be able to store all that, a case management system for if something happens, like where does it pop up? So that was compliance.

Recently we added a capability to push the data warehouse, for example. Again, once you have a lot of data, you probably want to store it. You can have a bunch of data and data analyst tasks that might be related to finance, but they could also be related to product analytics and other things. And you are going to want to be able to push that data into something like Snowflake or Databricks or Redshift or something like that. And so having all these things out of the ready out of the box is valuable. So that's another piece that we've added.

Then the most recent thing we added is what we call the reconciliation engine. Building recon around everything that happens in your bank account is something that's really valuable.

When you think about being able to see in real time, what is happening in the product, in the bank account, how do you actually get like, a snapshot without having to do month close, without having to have people go and manually assign categories and things like that? It happens at every company. And so we've built a lot of these pieces into both an API and app so that you can get moving with this operating system for money, movement, vision.

And when you have an additional problem and you're like, “Oh, I wish I had a data warehouse connection. Oh, I wish I could track this stuff.” It's right there. It's an app that is ready to go.

Turner: Interesting. That was actually one of my first or second corporate internships. It was corporate accounting. I just did bank reconciliations for, I don't know, 20 hours a week. I blocked that period from my life.

Dimitri: Yeah. There you go.

Turner: But yeah, it was interesting. It was like good exposure to just how complicated it was.

Dimitri: It's drudgery. Computers should do this. Computers are actually pretty good at this, but we just haven't invested in the tooling and the connectivity for this stuff. And so we have college interns, high school interns, whatever you are like going and spending 20 hours a week doing basic math and categorization.

Turner: Yeah, and it's so interesting, the math of accounting. It's pretty simple. You add $3429.86 plus this other random number. It's easy to do that, but there might be rules about when you add things. You have to find these different pieces, link them together. It's more rules-based.

Dimitri: Time is a really interesting aspect of it, right? There's all these rules of like, “Well we spent like a hundred dollars today, but actually it's over the next 12 months that we're going to recognize $8 of it every month.”

Turner: That was always a nightmare. You talked about this, that there was not good timing initially with some of these people who built this, but you started finding a bunch of customers. Was there a weird timing shift where suddenly everyone was ready for it? Or was it just new startups being created? Like how did that play out?

Dimitri: I don't think that it was like a timing. There's more, there's probably more startups being created in that period of 2018, 2019, 2020. There was a little bit more money in the venture ecosystem. Founders probably got a bit more ambitious and so people started doing startups that were not DTC e-commerce things. They were actually moving into these old school industries.

You start seeing payroll companies that were startups that would offer payroll services. They're going to be like Gusto that did that before, but they're more unique. All of a sudden there was a little bit more of that.

There were companies that were innovating like Sana in health insurance, which would be nobody's top three choices for a startup area, but there's all of a sudden more willingness to try things in that. Again, I think it's a combination of founder ambition and willingness to fund from VCs.

I think there was an element of there being more companies that were moving into those sectors, and they all basically were encountering the problems that we saw at LendingHome. And sometimes we would get introductions.

We did a lot of content, so we'd try to get people when they Googled some of these kinds of ACH error codes. We wanted to be in the top places online but also when they talked to the banks that they were trying to work with and said, “How would they actually get going?” Sometimes the banks would say, “Hey, a lot of our clients have used Modern Treasury. It's good. Go check it out. Maybe that helps you.”

And our pitch to some of those companies just getting started, it's really less about efficiency because they don't have volume yet. They don't have the problem. Their problem's a lot more engineering heavy. So it's like, how do I approach this and how do I automate this and how do I focus on my actual business and not make this problem go away, but also at the same time keep it clean and keep all of my finances in good shape? So that's something that we sold into a lot of those types of companies.

And then over time we scaled into bigger companies that maybe do have those efficiency problems. And they're actually thinking about moving around some of the ways in which they're doing things across different teams or geographies or banks or things like that.

But yeah, a lot of it came from companies, and many of them have grown a bunch and many of them are customers of ours today. They're not three people, they're 300 people. And that's super cool to see.

Turner: And then too, to your point, with having an expanded product suite, it's probably easier to go to a large company and say, “Hey, we're not just doing this one thing, and you still have to be sick. It's everything. Like you can't actually replace us smoothly without interrupting too much.”

Dimitri: Yeah, and I think the wedge product can be different at different stages. Regarding the earlier companies, we end up spending a lot of time with the product and engineering teams because they're really just building the product and they maybe don't even have a finance team at that point.

When you're talking about companies in the hundreds of thousands of employees, they definitely have a finance team and sometimes, they're burdened by a lot of volume, like fast growth, things like that, that make them look around for solutions to be doing things in a little bit less manual ways.

Turner: Yeah, and you had a really interesting point where you talked about making content and people would find it. Sam and Chris both mentioned, you guys leaned into this, product-led growth, PLG approach. You found that it didn't work that well in a lot of cases.

A lot of people talk about how great PLG is. Can you just talk about what you guys experienced there and then what ended up working at the end of the day?

Dimitri: I'm not sure I would articulate it as PLG didn't work. I just think it didn't work for the full set of the customers that we wanted. You know, there were companies like Twilio, who were the darling, back in 2019, 2020 of every investor.

And one of the things that people would associate us with is “Oh, are you guys building Twilio for banking?” Like, that sounds valuable and that sounds good. We would like look at each other and be like, “Are we what Twilio is for banking?” Nothing against Twilio but there are no carriers in banking, so I'm not sure exactly what that meant.

The thing that was really different is Twilio has a well-known PLG motion around somebody that is a developer in a company that has a thousand people who has to go build something that sends a text message.

They will use that and they'll bake it in and all of a sudden, they come back and they're like, “Oh, wow, we're sending a lot of text messages. We should really be an enterprise customer because it's growing like a weed inside of that product.” There's companies like Uber which is a famous example. They sent a lot of text messages as they grew quickly.

If you translate that into the world of payments and banking, if you, as a developer, are sending out a lot of wires, somebody's going to come and ask some questions. It doesn't work like that, it's just a different product. It’s more like a top-down sale in the sense that you have to get the CFO, the CEO, and whoever to approve this and to go connect to the bank and be able to close the books on it. And there's just a lot more that goes into that.

And, so we spent a lot of time in 2019 really improving our product, which it absolutely did. Trying to make the product faster to get started with, trying to understand how do we get somebody to get them to the point where they’re making their first, whether it's transfer, reconciliation, whatever it might be as soon as possible, to get to that point of demonstrated value.

Turner: So it was a top-down sale, but a really quick time to value.

Dimitri: Hopefully, yeah. Or can demonstrate the value. You can demonstrate how it works, and then you can almost in the sale, demo it for somebody. Like that's a very valuable thing.

But we didn't invest in building a sales team – for longer than we should have – because we believed PLG was going to take care of it. But we actually needed to go and spend time and build the muscle in the organization to do this.

PLG has taken us down a road that made our product better, but actually didn't advance our sales capabilities for enterprise companies. And that's something that we more recently have built out a lot more of.

More of general point is that the valley goes through these hype cycles. People get very enamored with something that works and they try to copy it into every different industry. And you have to think about it from a first principles level and say, “Does this apply to the industry or the customer set or the product that I'm selling.” What we discovered was, it's just a lot harder to send a wire than a text message, which is maybe an obvious point.

Turner: Very obvious, but maybe not quite at first glance. I've actually heard someone describe PLG as a pipeline strategy, not a sales strategy, which I thought was a good way to think about it. It sounds like that's what you said also, but you just had a way better, deeper explanation.

Dimitri: I mean, anything you do that has any engagement with, it's a pipeline strategy. So yes, PLG is definitely pipeline strategy. To me, the successful PLG products or I should say products that PLG should serve well, are products that are lighter to experiment with and are easier to get started with. It's just not the case in all things around payments and banking, finance.

Turner: So you mentioned, the product evolving in 2019. Is that when you raised the seed round?

Dimitri: We raised a seed round in 2018, so we raised a seed round at the end of our YC summer demo day.

Turner: And then you raised the series A in 2019.

Dimitri: Yeah.

Turner: So when you raised the seed round, you said you didn't have any customers yet. How did you convince people without any customers? Because if I'm an investor, I'm looking at the pool of YC, all these charts that are going up into the right – Modern Treasury didn't have that necessarily. What was the pitch and how did you get people to invest?

Dimitri: I think at the end of the day, a lot of it was really like relationships that we had before. So, for example, the founders of LendingHome invested and they were very familiar with the problem. The problem spoke to them. They knew us. Those types of connections, you build it over years, and whether you have a contract in the first 60 days or not, is less important to those types of investors.

We didn't raise from that many folks that we didn't know before. We really were like focused on either people who we met in the journey who understood what the problem was because they had built it at other companies and maybe they were saying, “Oh, you know what, I don't know that we can be a customer because we've already built it, but oh boy, do I understand this problem!”. That was a subset of some of the investors.

We kind of did a party round. And so there wasn’t one major investor, but it was people who we'd worked with before who were a part of it. We raised that August or September of 2018.

Turner: I think you mentioned throughout 2019-ish, the product got some customers, and then Chetan at Benchmark, ended up leading your series A. How did that happen? Like when did you meet them? What was the process of convincing them?

Dimitri: We met Chetan through a company that was in YC with us that he led the round for as well. A company called Duffel out of London. And Steve Domin had become a good friend during YC. And so he at some point was visiting from London, and he was in San Francisco. He came by our office and he just said, “Hey you guys should get to know Chetan because I think there will be an interesting conversation to be had.” And so we met up.

It was probably July, August of 2019, something like that. We were five people, we'd made two hires, but we hadn't grown that much as a company. It was a year plus into the journey and we had probably 8 or 9 customers at that point.

The thing that was cool – I don't want to speak for him – but I think one of the things that Chetan appreciated about our customer base is even though it wasn't that big and they weren't paying us that much money, it was very diverse. From the very beginning, we had customers that were in all different industries and even different sizes.

I think at that point we had a company that was public that was using us and we had obviously seed stage companies. And it was across real estate and payroll and benefits and mortgage and I think we all were going slow and methodical, because it was such an important thing for this type of product to not move fast and break things, but you could see that it was going to be relevant for a lot of different companies.

Turner: I think you've said it. I know Chetan said it. You go slow to go fast.

Dimitri: Right.

Turner: With YC, it's like you didn't seem like you were making any progress when you were going through but you actually made a lot.

Dimitri: And whenever you look at one of those compound charts, right? Like when you look at like 1% growth per day or whatever, the first 80% of it is not very exciting. But what you want to make sure happens is you're laying a foundation – technically and product understanding wise and customer, reputation, content, things like that – that pays dividends later.

Turner: Were there ever points throughout that process where you were impatient or like “I wish this was going faster!” ? Did you ever feel that and how did you stick with what you were doing and know you were doing something right.

Dimitri: I mean, I always feel like that. There were definitely moments. I think that early on, one of the things that was just very hard for us is getting ourselves taken seriously by some of the banks that we were trying to partner with and work with.

It's August, it's seven, eight weeks into YC, we're waiting for an email to come back from some bank, and they're on vacation. We're not funded and don't have a product up and running. So there's definitely moments when you look at and you're saying, “What am I doing?”.

But I think that, again, going back to ethe formative experience for us was that we were the customer that would've been a great customer for this product when we were at LendingHome. And so we just never had any doubt that this was like a product that needs to exist.

I think our mental model was “Well, if they're on vacation, maybe I'll go on vacation, but I'm still doing this until it's five basically.” It's when you're getting into B2B types of things you have to be okay with some amount of hurry up and wait in your business.

Turner: So this was summer of 2019. Did anything interesting happen between then and March of 2020 or was March of 2020 probably a pretty significant moment?

Dimitri: We doubled in size, so we hired a few other folks in engineering and others. We had an offiste February of 2020 in Tahoe and we brought together like 12, 13 people and it was basically all the full-time people in the company and a couple of advisors and things like that. We talked about values, we talked about culture, we talked about how we want to grow up as a company.

It was a very fortuitous timing because obviously in March 2020 we stopped doing offsites for a while. And it was very good that we had managed to do it right then and sneak it in before we went fully remote because we grew a lot more in the subsequent 12 months just in terms of headcount. And so having that culture piece set ahead of time was really formative, I think.

Turner: What were the most formative things about the culture that you set, or advice that you'd give to anyone else thinking about it?

Dimitri: For us, one of the things that we really keep coming back to is there's a certain level of natural curiosity about businesses. about the world, but specifically about businesses that you have to have when you're working at Modern Treasury. And that's like something that we try to lean into.

There's an element of we help companies build their businesses in the sphere, like in a nerdy, mechanical way. And we get together and we whiteboard where the money comes from, where does it stay, where does it get transferred to? What’s the timeline? What’s the cash conversion cycle? All the things that I think is super fascinating. but not for everyone.

Some people would find that boring, but we just find this almost business school case study element to all of these different businesses. Super interesting. And then we, of course, help them actually design and put it into, put into motion.

One of the things that we really leaned into is: how do we as a company both look for that but cause it inside of the company. So as an example, we started these “coffee breaks”, as we call them, when March 2020 happened. Obviously, we're working wherever we were. I remember having a few of these Zoom happy hours that were just horrible. They were so boring. It was awkward.

First of all, happy hours don't work if it’s like a monologue from somebody. And I was like, we need to get some free entertainment. We need to start inviting some people to share with us things that they find interesting. And that's taken life of its own where now we try to have them every other week or something.

We bring in people who are founders, investors – people that work for some of the companies that are customers of ours, some people have no connection at all to anything except somebody knows them as a friend – and they would just have an interesting story for us. It’s one of my favorite parts because I just find it super interesting to just learn about these things.

I think maybe the generalized advice is, as a company, figure out what you want to really encourage and then find ways to drive that.

Turner: Yeah, you just have to be really intentional setting what you want and just living it and delivering it.

Dimitri: Also, I think as a founder you have some outsized impact, culture is emergent from the people that you bring into the company. It’s not something that you decide and so shall be.

Turner: Yeah. It's like you do decide it because the second order effects of your decisions are really what drives it.

You guys just ramped up hiring. Did you raise money and you had to hire, or was it like customer pull? Like you just needed a bunch more features?

Dimitri: It's all of the above. Our product was getting more ready, so we were getting to the point where the PLG growth was working to some extent. It wasn't maybe working as well as we wanted it to, but we were bringing on a bunch of companies.

We had to spend time with them. We had to add new banks. We had to do all kinds of things that were really just a factor of having more money, but more importantly, having more customers.

And so we started bringing on people that had seen this problem before at other places, people who had other careers that were relevant for us, whether they were coming from banks or coming from other tech companies with more scale.

Content was a big investment for us from a marketing perspective so we spent a lot of time on, how do we make sure that we build Journal and Learn, which is our Investopedia for all kinds of payment ops terms and things like that which would bring people to us when they were in that moment of trying to think about how to build it.

And we were like, how do we intercept them and how do we make sure that our name is known? How do we make sure that they come to us and before they build too much, they know that there's an option to not build it? It's a new type of product so it wasn't immediately obvious to everybody that you didn't have to build it yourself.

Turner: Yeah. So what type of content was it? Was it like, “Hey, here's how to build this. By the way, just use us instead. We just did it.”

Dimitri: Some of it was just discovering new things as we were going along, learning about it, and then sharing with the world. It was a little bit of the “build in public” concept.

I think it's fascinating actually. There was like this hole in the content world. There is so much content out there as an investor, questions of “Is this a good business? Is insurance a good business?.” Warren Buffett has letters telling you insurance is a good business.

But if you're like, “I want to start an insurance company,” nobody's like, “This is how claim payouts work. This is what you have to build in order for claim payouts to be smooth. This is how reserve accounts should be set up.” All those types of things that are more mechanical in nature, nobody was writing about.

What we discovered was, when somebody decides “I am starting an insurance company,” they want to find out how it works. There was a hole in the content world and nobody tells them, “This is what you do. Here's the five steps.” And so, those are the types of content you can find on the Modern Treasury Journal today.

You can go back in time and see the earliest posts. Some of them were change logs and things that we were actually launching, but then a lot of them were like, “If theoretically you were doing this, here's how you would do this, and here's like the IKEA manual for building your business. Forget about whether it's good or bad, or if interest rates change it. Just mechanically, if you've decided to do it, now what?”. That was a lot of the content that we put together.

Turner: Do you think that’s necessary? Like finding a marketing hole or some go-to-market that’s undervalued or super cheap CAC where customer acquisition costs are really low. You almost need something like that for a startup to work.

Dimitri: I think it's important. Most companies when they get started and experience somewhat rapid growth, there is some mechanic that's working. There's a growth loop that's really hitting, whether it's something that's intentional or discovered by accident.

Oftentimes there's a platform shift or something that changed in the world in general that drives a behavior that all of a sudden people can find. But if you think about the ingredients that are required for a new startup to be successful, obviously a product that solves a problem is step one. If you don't have that, I think it's hard to scale that. But I do think distribution is incredibly important and in a lot of cases, maybe even more important than a product.

Sometimes you see companies or people will say, “Oh this product isn't actually as good as this other one. Like why is it winning?”. And the answer is usually something to do with distribution.

So whether it's CAC – I think for us it was even less an economic thing and more like how do we intercept the conversation when somebody is actually thinking about these problems – it’s a big question for a lot of companies. We're not going to convince you to go buy this product out of the blue today, but when you have the problem, we want you to think about us. So there’s a brand element which is pretty important.

Every company that succeeds, if you actually look, it's not smooth. There's like these wrench turns, and people figure out like the next thing that lets them grow. Or sometimes the mechanic dies for some reason.

But thinking about growth loops and things that drive people and eyeballs and conversations towards you is – I don't want to say it's more important than the product, but it's only infinitesimally less important.

Turner: Hmm. Were there any moments where maybe it broke for you guys and you had to figure out how to fix it?

Dimitri: Earlier this year, both kind of. Conversations initially at the top of funnel and bottom of the funnel closing are reliant on a healthy US banking system. And so in March of this year when we had a number of bank failures, we saw a month or two where a lot of things slowed down. And because people were super distracted and they were focusing on other things (it was arguably a good thing in the long term) but in the medium term, it was a very painful moment – both painful to watch as friends and partners of ours went through some pretty difficult times, but also painful for us in terms of like the impact it had on our pipeline.

Turner: Yeah, and it happened at a really interesting time too. The story that I heard was you were at an offsite planning. You weren't really at your computers ready to react to this. What happened?

Dimitri: Well, it happened a few days after our sales kickoff. It was the week when, when the SVB failure was. We had everybody together. We talked about how to work as one team, one dream. And then we went across the country and then immediately were thrown into a moment when we all had to work together in a very coordinated way.

I suppose it was well designed in a team building sense but yeah, it was, a crazy thing to live through and to see up close.

Turner: Can you take us inside that day or that week or month? Maybe it's still ongoing. What was it like inside of Modern Treasury? How were you helping your customers?

Dimitri: Yeah, so to take you back to, I think it was March 9th if I'm right, that Wednesday and Thursday, basically all of a sudden there started to be a lot more messages and tweets and questions were coming from founders, from customers, from VCs about companies’ reliance on SVB and the single bank question that people were having, which was, “Do you have another way to operate your business?”.

Now remember that for most of our clients, it's not just corporate cash sitting in some account, it's actually very core to the operations of the business. And SVB had been a very good partner of ours from the get-go. We had a lot of companies that were primarily banking with SVB, sometimes solely. We really were focused on serving our customers well, but that meant a deeper, better integration with SVB for a lot of them.

There was the snowball effect and one of the things that we had to think about in real time was, do we want to encourage panic or not? There was a lot of panic in the air. People, at the time, felt unreasonable. But then it's one of those game theory things where if everybody's freaking out, it doesn't matter if the reason is right.

We were helping customers one-off on Zoom calls and phone and then one of the things that was really interesting – on that Friday at maybe 10AM Pacific, the FDIC took over and publicly said that SVB is now taken over by the federal government. It was a crazy moment because it's something that you've read about in books but you hadn't really seen for a long time, at least not to a major institution in the US.

One of the questions that we immediately started getting from the companies that were working with them was, “What's happening to our business? We have to go process certain payments for our business next week on Monday. What happens?”.

One of the things that we realized was that there were a lot of questions of, “Well, is the system actually working? Can I log in? What would happen?”. We had connectivity to a lot of different systems at SVB, and so we could actually monitor and see. So we put together a status page, a third-party verification of the live status of these things.

Landing page for the Modern Treasury SVB Resource Center. Source.

We felt helpful in that because we actually had a unique view into some of these systems in a way that other people didn't. Also, it was very objective and we weren't trying to grow the panic – we were trying to provide a useful service.

So we started publishing that and updating that every couple of hours. Pretty quickly after, people might remember, there was another bank called Signature Bank that also failed that weekend and the FDIC took over, which is also a bank that we supported. And so we put together that template for the status page for another bank and we kept updating it.

And as we rolled through the following two, three, four weeks, you started seeing a lot of activity across companies trying to explore other banking options, or they're trying to make sure that their accounts were in good standing to get funds moving again. And we were updating and helping companies all throughout.

From a crisis communications problem perspective, we were very focused on: how do we provide a good useful service that we could put out into the world without causing panic, without causing people to freak out more? It was a fascinating to live through.

Also as a company, as a team, going through something like that together is like very formative because we had a lot of Zoom calls on the weekend where everybody was live updating. What are the engineers seeing? Is the status update happening or not? How do we actually upload it? Marketing, web, copy, all these things starting to move. It definitely galvanized the team to work a lot closer.

I remember that Monday… Ok so we were based in San Francisco. Our main office is in San Francisco. We opened a New York office the Monday after and we were gonna have a little party and none of that happened. We just moved in immediately and got to work .

It was like, “It's a good thing this office works. It's good thing we have wifi. Okay. Get back to work.” We never celebrated moving into our New York office, because it was literally the Monday that SVB came back online.

Turner: So you still haven't had the party.

Dimitri: We've had plenty of parties but we haven't had a true office warming party.

Turner: Maybe at the next coffee chat. Do you wanna move into rapid fire? A bunch of different questions?

Dimitri: Sure.

Turner: If you go back to the early days of Modern Treasury – anything you would do differently?

Dimitri: I think we would spend more time with customers. I think that we talked about the PLG piece, but there's nothing that isn't made better by just spending more time with customers. Whatever time I was spending on not talking to people about how they might want to use our product, I would not do.

Turner: Okay. That's fair. This is a question from someone on your team, Ani Narayan. He asked, where is your favorite place to go on a hike?

Dimitri: Oh boy. I would probably have to say the best outdoor hiking, backpacking trip I've ever done, it happened when I was in high school, so maybe it was like a formative time, but it was around Ross Lake in North Cascades National Park. I did a long backpacking trip up and down the sides of Ross Lake. It's a very long lake, it starts in the Canadian border and goes south.

Turner: Is this Washington?

Dimitri: Yeah. This is in Washington. It's about three hours from Seattle.

Turner: Okay, interesting. And that's where you grew up, right?

Dimitri: Yeah, I grew up in Redmond, which is twenty minutes east of Seattle.

Turner: Ok. And you send these weekly Saturday notes to the company. What are those?

Dimitri: Saturday notes are one of these things that just evolved as a tradition, but when we started being a little bit more distributed and a everybody was focused in their own little world, it felt like something that was good practice for me, sitting in the middle and getting a little updates here and there from different teams to share back.

It was like, “Here's something that is really cool too that happened this week. Here's a customer we saw and here's somebody who's joining next week. Here's our coffee break guest for next week. It just evolved and as we've grown (we're 160 people now), we still do them.

Maybe some people read them, some people probably don't. But it's a good way to, keep the company updated and share some of the things that are cool that are happening in different parts of the company. Maybe if we were all in one office, it would just naturally happen more, but especially when we're all remote, it’s particularly hard to highlight those things.

Turner: So you synthesize everything going on and fill people in on maybe the things that are most important or that you thought were good lessons or learnings? Just keep information flowing?

Dimitri: Correct. It's almost like a little investor update thing, but it's like across the company. It’s like “Hey, kudos to somebody who's done something really good.” It's a little bit more team-focused, but if there's a week that goes by and you can't point to ways in which your company's better off or has grown – and it could be a bad thing too, doesn't have to be a good thing – but there has to be some delta after you spend a whole week. Otherwise, what are you doing?

Turner: I've also noticed you seem to do a lot of reading. You mentioned earlier you really like studying business and learning all these different lessons. Do you have a favorite business story or book?

Dimitri: Favorite business story or book? I have a ton of them.

Turner: While you're thinking, I'll also give a shout-out. You have a Medium page. If you just search Dimitri Dadiomov, you'll find it. You do reviews every year, you have a bunch in there. Do you have a favorite that stands out?

Dimitri: I think one that just jumped out at me is Robert Caro. He’s this writer that writes these massive biographies of folks and he has a little, tiny book called Working and it's about his way of working.

He's famous for spending 10 years doing research before he writes a book. And so he knows everything about something and it's super well written and he focuses on the descriptions and the place and the title and the rhythm… It's like fiction-level writing in a non-fiction book. And so anyway, his long-form books are really good.

I specifically think Working is interesting because – there's a Charlie Monger quote that's like, “Life's all about like taking a simple idea, but taking it seriously.” – and I think that's something that he does in his life.

I think that it goes for startups or for anything that is around craft and you have to focus for a long time. That mentality is really good and he's just like an extreme version of that. So, Working by Robert Caro.

Turner: Working. Okay. And then last question: you've probably studied or read about a lot of founders and CEOs over time. Do you have a favorite? Doesn't have to be current, can be all-time historical too.

Dimitri: It’s hard to just pick one, but I think the people that I really admire are the people who go out and build something that takes a long time to bake. People look at it and they don't quite know like what it is for a while.

Warren Buffett is a perfect example of this where I don't think that people in the 1960s held Berkshire in high regard but he proved them wrong. Jeff Bezos has elements of that as well, where a lot of people thought that Amazon was just burning money, and it was like, no, they were actually building warehouses. There's lots of examples of that.

Craig McCaw is like that as well. He started at McCaw Cellular, which became AT&T Wireless, but he was the first person to say, “You know what, we're gonna go and build a bunch of towers and put cell phone antennas on top of them.” And nobody thought that was a business that made any sense. And then, he proved them wrong.

Turner: Yeah, it’s pretty important nowadays. All the different companies that we've mentioned in the last hour and a half have all relied on cellular data in some capacity. I actually have another question. Do you have any questions for me at all on anything?

Dimitri: Well I’m curious about the way you started investing and grew in this meme way to get in front of founders, get in front of investors, et cetera. The world has gone through all these different changes just in the short time that we've been in business as a company like five years, and I just think about the world of 2018-2021 – every year is completely different.

There's a pandemic. There's no pandemic. The markets are crazy. The markets are not crazy. There's bank failures. There's no bank failure. So I'm curious how do you think about the next year given how fast things are changing and moving? We were just talking about superconductors right before we started recording – that was a hype cycle that was about 10 minutes long. How do you think about investing and what you should be spending your time on?

Turner: I'm just really interested in learning about businesses and how things work. I don't ever think I would be able to start a Modern Treasury, but I think I'd be good at investing.

When I think about just what's my advantage – I don't live in San Francisco. I'm there, maybe every couple months, I’ll spend a week there. But I live in Michigan, so for me it's almost an internet-first approach. It's almost like a PLG approach.

Initially this was probably 2017, with serious content online and Twitter, I saw this opening in the market, like when you talk about like different channels that are maybe undervalued or like where the opportunity was. It was kinda like, “Huh, people love memes. Everyone takes themselves super seriously, all these VCs. So what if I just make some memes?”.

And then I tilted towards that and I was still doing more serious stuff, but the memes almost took over, and that's how a lot of people got to know me. I still do them but now it's like, “Alright, I should probably start doing some more serious stuff too, right?”.

I've been doing this for five, six years now. I started with Twitter only, and then it was blog, added a newsletter, podcasts, and then we're recording this in video so this goes up on YouTube and we'll put clips. I just think about it as: how can I do these things to leverage my time and founder's time to help them? It’s a PLG approach to VC in a way.

Dimitri: I still remember, for whatever reason, there's a clip that you did and it was probably 2020 of a VC that's trying to take a meeting with a founder, but one of their Teslas or something keeps being stuck or not charging or something. And they keep interrupting and going back. The nanny is driving the other Tesla or something. Anyway, it was just spot on for some experiences the founders have with VCs in some cases.