🎧🍌 Growing Medal to Tens of Millions of Users | Pim de Witte (Co-founder and CEO, Medal)

$1.5 million in revenue at 13 years old, why consumer platforms need social inflection points, Medal’s unique approach to in-person / remote work, and why rapid iteration is everything for startups

Stream on:

👉 Apple

👉 Spotify

👉 YouTube

The episode is brought to you by Secureframe

Secureframe is the automated compliance platform built by compliance experts.

Thousands of customers like Ramp, AngelList, and Coda trust Secureframe to get and stay compliant with security and privacy frameworks like SOC 2, ISO 27001, HIPAA, PCI, GDPR, and more.

Use Secureframe to automate your compliance process, focus on your customers, and close deals + grow your revenue faster.

To inquire on sponsorship opportunities for future episodes, click here.

My latest guest on The Peel was Pim de Witte, the Co-founder and CEO of Medal.

Medal enables millions of gamers to capture and share their favorite gaming moments with friends. Pim started the company in 2015 and has since grown the business to millions of Daily Active Users and raised over $72 million, supported by investors like OMERS Ventures, Makers Fund, Dune Ventures, and Horizon Ventures.

Pim built one of the few consumer companies that grew both during and after COVID. I really enjoyed our conversation talking all things gaming, social networks, and company building.

Topics include:

Why people play video games, and why 200 million gamers play Roblox

Learning to code at 13 years old to build a private Runescape server that did $1.5 million in revenue

Why paid acquisition is so important in mobile gaming

Why consumer platforms need a social inflection point

How Medal blew up during COVID

Why multiplayer platforms die when network effects unravel

Why Medal’s Seed round was so hard to raise

Pim’s biggest mistakes building Medal

His three favorite interview questions

Why it’s a mistake to focus on competitors instead of customers

Medal’s unique hybrid in-person / remote work environment

Why rapid iteration is everything

How Medal acquired six other startups

Why building product is the ultimate game

How Elon’s changes at Twitter caused a great reset in tech

Find Pim on Twitter and LinkedIn

🙏 Thanks to Zac and Xavier at Supermix helping with production and distribution!

Transcript

Find transcripts of all prior episodes here.

Overview of the Gaming Market

Turner: So I thought we could kick things off - can you really quickly give us kind of a high level crash course on gaming as a market, how big it is, and why it’s interesting?

Pim: When you're a kid, you can choose between spending time playing out any scenario you can imagine with your friends in a digital world versus scrolling a feed that's going to give you entertainment. And I think most people pick the first one because it's more fun and more interactive, and friendships are made.

It's kind of ironic that there are social networks that are claiming to be “social,” but it's actually way more social to drop in and do something with your friends inside a video game than it is to scroll a feed in isolation. And so what we try to do is enable people to capture, edit, and share the memories they create with friends while they're playing video games.

Turner: A way to think about it then would be: 20 years ago, someone might play outside at the park and today, they might still play outside at the park, but they also might play with a friend who lives across the city or across the country or the world online, together.

Pim: Exactly. I would say it doesn't necessarily replace it, but it does give people the ability to do that regardless of where they're located. Our mission at Medal, or one of the things we say is, we think that Medal is inherently good because it creates a more connected world where you can have friends all over the planet.

I think it creates a level of understanding that people have about each other, that transcends beliefs and things like that. And so I don't think it replaces playing outside. I think inherently it just removes the location element from doing things with your friends.

Why Playing Video Gaming is a Social Activity

Turner: And I remember too, even when I was growing up in high school, I probably met just as many friends in class and at school as I did first playing a game like Call of Duty or Halo with them and then hanging out at school or in-person.

Pim: In my case, it was very similar. So I have Tourette’s, so for me, it was tough to make friends at school. I have a lot of good friends that I have from that period, but for me I was always kind of like the oddball. You can still kind of see it, like I twitch my eyes sometimes.

With games, there were no barriers. I was just like everyone else. And so I think, for you it's an adjacent place; for me, it was the place. It was where I didn't feel different.

Turner: I would actually say for me it was probably the place too. I played a lot of Halo, Call of Duty, Gears of War - those kinds of games growing up. And yeah, I made a lot of friends in high school, like I said, through gaming. And what would you say is the big title for that right now? Is it Roblox? That's kind of what I hear?

Pim: Definitely.

Turner: Can you explain to us what Roblox is and how big it is?

Pim: Roblox is essentially like a virtual sandbox that lets you create any type of game you want and invite your friends to come play it. But that can be five friends or 50,000 friends. And it allows you to monetize as these experiences get to scale.

I think the reason why it's doing so well compared to the rest of the market is – one, it’s cross-platform. So if you study network effects, one of the predominant factors that determine whether something is successful or not is the K-factor. And if you look at the K-factor of Roblox versus other games, the fact that Roblox is literally everywhere makes it so that they are able to capture a much wider audience than most other games, primarily mobile, I would say.

They are really one of the only companies that have really nailed that mobile to PC loop. And I think a lot of companies just haven't done that yet. And if you have both mobile and PC, you have a lot of the most social gamers. And so I think the loop that drives Roblox just runs faster than most other games.

The other thing that's going on with Roblox, which is really interesting, is that COVID drove a really, really large slowdown of content production across the games industry. That didn't happen with Roblox because it's just people making these games.

And so, if you think about it, with content becoming increasingly stale, the largest multiplayer games release that got more than 10% market share on Medal was Valorant. Realistically, content is delayed because of COVID and as a result that's where the freshness is at now. Roblox and GTA 5.

Turner: Most of the people “creating content” on Roblox, or creating games that you play, and it's mostly kids, right?

Pim: Yes.

Turner: What's an example of a game like? I'm just trying to give somebody an idea of playing a game on Roblox.

Pim: Yeah, so it can range from Neopets where you basically raise pets with your kids or with your friends. Or there's FPSs[1], they're kind of like CS:GO, most popular games have a version of them in Roblox.

One of the more recent trends is this game called Only Up, which essentially is like a nearly infinite game. And this is a game that goes mainstream regularly as a standalone, and then Roblox users catch on and they make their own versions of it. Also very popular on Fortnite Creative now.

So you're kind of seeing this shift into games being these trends that fade in and fade out. And, I think in a way, Roblox is like the TikTok-ification of games where attention spans – the amount of time that people are actually willing to invest in a specific game loop before they're sold – is pretty low.

And so they play on Roblox and then, if they're not into it, they'll go play something else. And if they are into it – soccer for example is a popular Roblox game – you might have some friends there and transition into professional FIFA or whatever.

I look at Roblox as kind of like TikTok for games because the retention, like on the tail end of these games, is pretty low.

[1] First person shooter games are ones in which the player takes on the role of shooter and experiences the action through the eyes of a main character

Turner: But there are always new ones coming out.

Pim: Yeah, there's always new stuff. I mean, it definitely moves quicker than the traditional games industry, but people still flock to like the main ones. But the tail-end retention is single digits percentage, people who come back on Day 30 versus Day 1.

And so what you see is that these games are like TikTok. There are pieces of content that people consume and then once they're done with it, they're done with it. And I'm sure there are exceptions, but that's really what's happening in Roblox and I think most industries haven't really caught up with that yet.

Turner: So it's almost like – a way to think about Roblox is that it's sort of its own game engine. In a way, it’s a game, but it's almost its own platform that other people build games on top of.

Pim: It absolutely is.

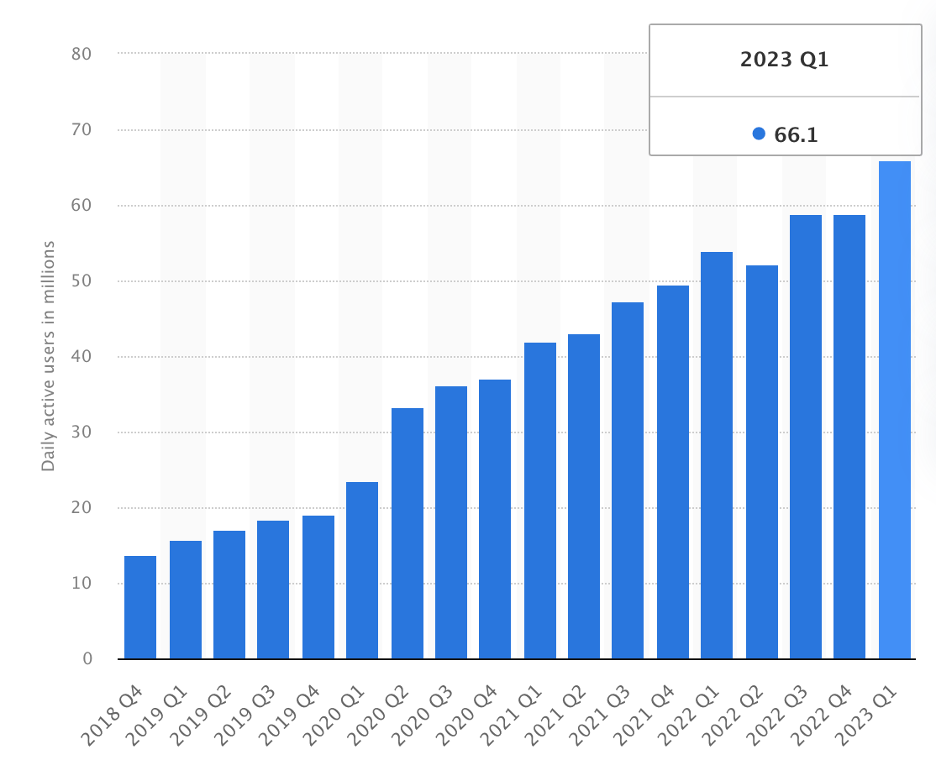

Turner: Yeah. And how many people use it now? Is it 40, 50, 60 million?

Pim: Don’t quote me on this. I believe they have a hundred million daily active users, or in that range, give or take. It's like somewhere between 50 and a hundred million at the moment, I’d have to check.

Daily active users (DAU) of Roblox games worldwide from 4th quarter 2018 to 1st quarter 2023. Source.

Turner: And then you talked about Roblox having a really good loop. What exactly does that mean?

Pim: Okay. So if I'm playing a game on Xbox and it's an Xbox exclusive and I try to invite my friend who doesn't have an Xbox, then they're not going to be able to play my game.

You see this with GTA 5, for example. They don't have a mobile client. And so it’s very, very popular on PC, but they don't get to Roblox scale probably because there's no way somebody from mobile can actually access that. And so an optimized loop lets people play where they want to play.

If you think about it, for every four friends you invite, if only one of them can play, then your game is hypothetically going to grow at 25% of what it really could be growing at because you're inviting four friends. So Roblox is an optimized loop in the sense that the places where people want to play generally have a way to play.

Turner: It feels like they've done a good job with content on other platforms. Like people will make videos about a game that they made in Roblox, which will then drive more people to play Roblox as a whole, right?

Pim: Yes, exactly. Because the barrier to entry to create is so low, people will just create and then talk about it and see if it sticks versus game studios who spend millions of dollars building something without knowing if it's going to work.

Turner: And like we talked about, it's literally going to be a 13-year-old kid who makes a game that millions of people play.

Pim: And it's hosted by Roblox, scaled by Roblox. It's kind of magical.

How Pim Taught Himself to Code

Turner: Switching topics a little bit, that's sort of what you did back in the day when you — I think you were 13 or 14 — you had a private Runescape server. Can you first explain what that is for people who don't know, and then talk about what that whole business was?

Pim: Yeah. So Runescape, the original game, was written in Java. And so what that means is that they were distributing a client through Java applets on the web, which are executable JAR files and you're able to reverse engineer and basically turn it into your own version of the game.

Like let's say for World of Warcraft, you could go in and you could look at the code – not literally because it’s heavily obfuscated, but you could, technically. It's much harder to do with games that weren't written than Java.

There was a huge community – this wasn't something that I did personally – but there was a community of people that were really into reverse engineering the Runescape client. And, at some point we went from, “We can modify this thing” into “What if we actually build our own server that corresponds to these things that we can do in the client and basically have the whole thing.”

Turner: So you took the existing world and you just split it into your own version that wasn't controlled by the company that owned Runescape and you almost had your own?

Pim: Yeah, so it has to be very clear, there are different versions of this. This was “definitely not supposed to do that.” On Minecraft it’s encouraged, because on Minecraft you're connecting to the servers through the official clients, whereas with Runescape, there was no functionality for that. We distributed the clients that people would go to play with.

To be clear, you're definitely not supposed to do this, but I was 13 years old and I was really pissed off that Runescape removed my favorite part of the game and I really wanted that back.

Turner: What did they remove?

Pim: The wilderness. There were two punches. There was the wilderness and free trade. I really love the economy part of the game and they basically removed the ability for me to go kill other players for their items or for me to trade and merge items. That was the whole game for me and I wanted that back.

I discovered this private server scene, and then I got really into playing them. Then I tried to make a few and got super addicted to coding basically. I got as addicted to coding as I did to video games. It was like magic to me.

You can kind of imagine like, I'm a kid with Tourette’s in school, wondering, “Am I going to get a job? Is anyone going to hire me?”. And then I discovered this world of people making tons of money, doing this thing called coding. And you never even have to talk to people.

So for me, this was like the thing. And I would skip school and code, and I would code literally, all day, every day.

Turner: You were in eighth grade? Ninth grade?

Pim: I think this is when I was like 13 years old. So in the Dutch version, I was in eighth grade-ish.

Turner: So you basically learned how to code so that you could build your own server.

Pim: Yes, that's correct. And it's very common – a lot of kids, that's how they learn how to code. But that's how I started too.

In addition to that, I was into websites and stuff, so I was designing websites for people at school and selling them. I was basically doing designs in Photoshop and then exporting them to Dreamweaver and then exporting them from Dreamweaver, to usable HTML / PHP, and then I would sell them to people at school.

So, I was into all the different ways of code and then, obviously private servers took off, so I didn't end up working much more on selling websites. But yeah, I built the private server website and things like that and maintained that.

Turner: You've said before you had just a desire to build things that people used. What do you think drove that?

Pim: I don't know if I could pinpoint a specific thing. I just love building stuff and then people loving what I built. I don't think that there's a “recognition” that you're building things that people like… Again, as somebody who didn't get a lot of recognition from peers as a kid because I wasn't exactly the popular kid in the school, I was looking for a lot of peer recognition and I think building products probably gave me a lot of it at the time.

Turner: I mean, as weird as it is, you almost get a lot of social capital from being good at gaming in some cases.

Pim: I think in my case, what happened, which is pretty funny, was that Runescape got so popular that the schools, they banned the IP addresses and websites from Runescape. But you could play my server.

One of the big reasons why my server became so popular is that we kept a memory limit and like usage of CPU really low so it could run on school computers. It would run on like 5,050 megabytes of memory. You could embed that in a web browser, in a Java app, and people would play my server instead of playing the main game.

I've actually had scenarios where I've been beaten up at school. Not really, like it didn't hurt that bad, but they wanted items in the game, so they were basically threatening me, like, “Give me items!”

On the other hand, people just came up to me and were like, “Oh, are you the guy that built the server? I love to play it.” and, “Prove it to me. I don't believe you. You're lying.”

It was really funny and as a teenager, that's amazing.

Running $1.5m/year Runescape Server Business as a Teenager

Turner: You got it up to ~$1.5 million in revenue. What were people paying for? Did they pay for access or items or something?

Pim: Well, I think the downside of an economy is that you lose sometimes. So people would buy items, they would sell them. If they died in the wilderness, they would buy more items. There were memberships. I had a lot of different ways. I even had ads on the web player where like if you played on the website, I would monetize with Google AdSense, for example.

Turner: And then when someone bought, what did you use to facilitate the transactions back in the day? Was this like PayPal probably?

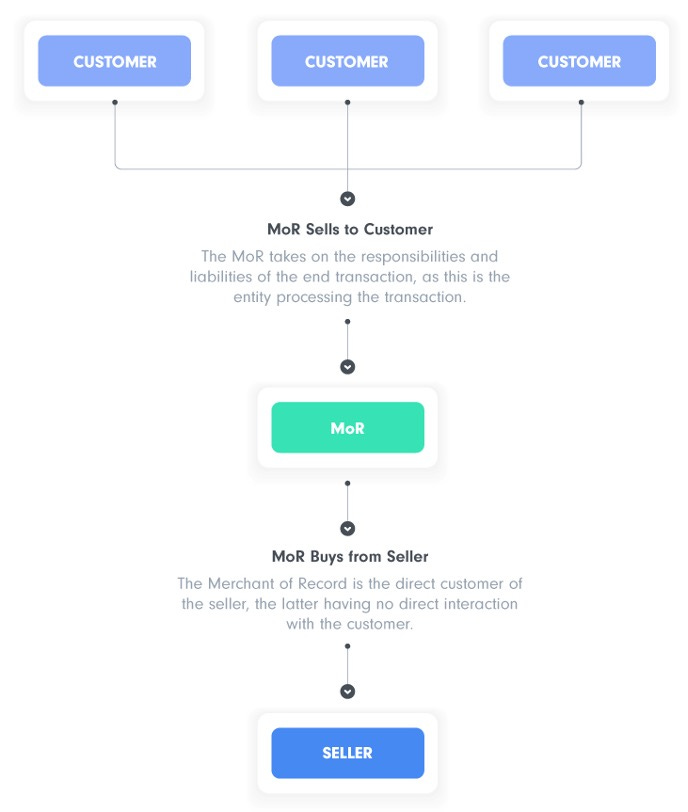

Pim: No. So you couldn't because the private server was a high risk vendor. So I wasn't allowed to transact with traditional payments platforms because we would be considered high risk.

We actually had to go through what they call a “merchant of record,” which basically blends a whole bunch of companies, like high risk and low risk, so their average risk profile is lower. As long as you stay under a certain amount of chargebacks, they'll keep working with you. We had a number of different payment providers, some not around anymore today.

How Merchants of Record work. Source.

Turner: I wonder why.

Pim: No, no. I mean, there are still merchants of records by the way. Inherently this model I think worked fine, because what they do is they kick out the ones that are actually very risky. They basically keep a baseline profile.

They might also have their own merchant bank where they go and work with a bank that is high risk, but inherently you have to stay under a certain amount. But that's how we got payments processed. And yeah, we got up to a million and a half in revenue when I was about 18 years old.

We lived in the Netherlands, so taxes and everything are really high, but for an 18 year old, that’s great.

Turner: And you had some employees that you paid too.

Pim: Yeah. So the cool student job was working for my private server. We had an office right next to university, within 10 minutes or so. And they would just bike there and check in as a support agent or as a safety specialist or as a technical help person. And they would make money by the hour and then go back to school.

There were very few full-time people. I had like four full-time people and the rest were just students that worked by the hour.

Winding Down His First Business

Turner: So what was the final outcome for a business like did you eventually just wind it down? Did you sell it or how does that work?

Pim: We wound it down because 1) I turned 18, which means I would actually be liable for stuff I do and 2) when I turned 18, I started talking to the company that runs Runescape and eventually we decided that it was best for us to shut down.

We tried a bunch of things that worked for a little, and then after a while decided that shutting down was the way to go. I want to say it was 2015 or so, so eight years? Yeah, in the summer.

Turner: Then that was around the time you started doing some hackathons?

Pim: I knew it was going to have to shut down a few months in advance. And so I started figuring out what I wanted to do next because a private server was good money, but at the same time, again, living in the Netherlands, I made good money, but not nearly as much as people think I did.

I wanted to figure it out – do I go to college to get a job? I had a good amount of money saved up, so I was like, “I can kind of just go do whatever I want right now.”

And so somebody at Doctors Without Borders where I had placed second, like I technically didn't win the thing, they kept in touch. They called and they were like, “Hey, we have this problem with local network infrastructure, which is very similar to the private servers you used to work on. Can you come solve it with us?”.

This was during Ebola, so I ended up going to Doctors Without Borders to work on this problem and liked it so much that I stayed for almost three years.

Turner: So this was kind of ‘18 through ‘21-ish?

Pim: This was ‘15 through ‘18, and towards the end of that, my co-founder I from Soulsplit (the company was technically founded in 2017), we started tinkering with and making games.

Towards ‘20, we released a mobile game that we built, and we self-funded it. It was just like our own money. The mobile game failed.

Turner: You tried to raise money for the game?

Pim: Yeah. And we actually ended up raising $150k at a $1 million valuation. At the time it was all we could get. Nobody was funding what we were doing.

Turner: Why did no one want to fund it? You had obviously built some pretty cool stuff.

Pim: Well, I think part of it is I was just a super random kid. Mind you, at the time, I was 20 and I didn't really know how the world works. I didn't know there was a Y Combinator. I didn't know there were VCs. I had tried emailing a bunch of VCs, but nobody really responded.

I reached out to some people in the Netherlands who I knew through mutual context from running the private server. They introduced me to some of their friends and they ended up doing $150k.

It’s pretty funny.We still have them on the cap table, and they were the first people that bet on us. But they were very happy.

What He Learned From Doctors Without Borders

Turner: Were you at Doctors Without Borders while you were working on Medal?

Pim: So the Doctors Without Borders projects – they were set budgets. I had a budget to deliver this project, which was, in this case, $50k. And I knew that Doctors Without Borders is a charity, so we delivered the project and it was doing well. And I started picking up work on my game after.

The project got taken over by Heidelberg University, which is a popular university in Germany, specifically when it comes to GIS work, which this was qualified as.

Turner: That's like mapping.

Pim: Yeah, mapping. So we got a very good home for it. Everybody felt pretty comfortable.

I started working on the game with my co-founders and built the game Shift. The game’s day one retention was great, but day seven retention was terrible.And what we found out is that you need player liquidity to hold people engaged.

We were hoping that would happen organically, but what we found out is that with mobile games, session lengths are so low that that's actually really hard to do without paid spend, where you push people at these similar times. We just didn't have the money for that.

Turner: Okay so in gaming, the strategy is typically like, you need to spend a bunch in spurts to just get a bunch of people at the same time.

Pim: Or at once, yeah. But generally spurts, because the problem is that when you get a bunch of people that are really good at the game, they'll beat everyone who's bad at the game and they'll all quit. So you need liquidity.

If you're building a competitive game, you need player liquidity at each of the levels. And the problem is that there are no actual levels because peoples’ levels are their skill at the game.

The amount of player liquidity that you need to actually build a successful competitive game is massive, which is why it's so rare. And so this is why when I see pitches for competitive games, it's very tough to say yes to, because of this particular problem.

Turner: And you started Medal as a way to solve that problem.

Pim: Exactly. So our theory was, we get a bunch of people to watch video clips on the platform, and then we send a push notification that our game is live a few times a day. Medal got so many downloads that we ended up deciding that Medal was the bigger opportunity.

Our thesis was that we could build this large gaming platform and eventually if it has enough layers, we can always launch games anyways. It kind of felt like a more organic way to do things, so we pivoted, and that's kind of the start of where we are today.

Turner: Maybe we can kind of talk through the Medal journey, but I'm just curious as of today, what is Medal like? How do you describe it to someone in just a sentence or two?

Pim: Yeah, so Medal is a camera for digital environments. Like this is what we're really good at. Whether that's a PC game, or a VR chat environment, for example. We try to be really good at capturing whatever meaningful thing is happening on your screen.

Then there's a whole platform behind where you can share what you captured. You can edit it, you can tag your friends, you can message your friends about the thing that was just captured. And then we figured out that when you actually capture these moments, it's then very meaningful to connect the people that were in these moments.

As of last year, we're now also really good at recommending who else was in the moments that you captured and therefore building a social graph on the platform, which then lets people follow each other and you can see the moments they capture, etc.

How Medal Works

Turner: Okay, so it's almost like instead of Facebook for your real photos that you're getting tagged from your friends or Instagram. You're posting and you're scrolling a feed of pictures from someone's camera roll on their phone. Medal is entirely moments from within Roblox or within a certain game that they might be playing on their phone or on their computer.

Do you guys have, Xbox and PlayStation and different consoles yet?

Pim: Xbox and PlayStation both have native video capture functionality, which you can just import through the mobile app. We do have an integration with Xbox specifically, which lets you pull directly from your Xbox. With PlayStation, not yet, but it's quite easy because they all have these moments in their mobile app. You can just share them straight to Medal.

I would say for mobile and PC we're capture for console. We're one step further in a funnel or more like editing and sharing.

Turner: And obviously you didn't start there, so what did you start with initially? The very first Medal concept?

Pim: We started with a mobile app that would pull all the top clips from Reddit, and show them in a dedicated environment.

Turner: Why did that work? Because you could just go on Reddit, I guess. Right?

Pim: It was more noisy and you had to go into individual subreddits. At the time it didn't do as good of a job yet merging the highlights from the different games. I think we also included some other sources.

For example, we had a Discord bot where people could go and submit their own clips. We built this Reddit and Discord integrated video consumption product that, people downloaded, but they didn't really stick with.

We got a lot of downloads – I think we got like a thousand downloads a day. However what we found when we actually talked to those people is that they weren't posting consistently because they didn't have a way to capture it consistently.

It was very hard to go from a game to a short video And looking back, that was because all those recorders were built for long recording. All of them are built either livestream or YouTube at the time. Nothing was built for short-form. I think actually largely this is still the case.

OBS now has some functionality to make it easier to export, like most platforms are making it easier, but most capture software is inherently built for long-form. And so we learned from our users, that it was really difficult to capture short-form, and we made it easier for them to capture short videos and send it to their phones.

Turner: And then this was before, TikTok was a thing?

Pim: TikTok was not a thing yet. So there were two things that happened that blew us up, Fortnite and TikTok.

Turner: What happened? How did you blow up?

Pim: Everybody all of a sudden needed easier ways to capture short-form video. And Fortnite in particular is super clippable, you know, constantly experiencing cool moments. In COVID, Fortnite was the place for your friends, for an entire generation of high schoolers. During their junior and senior year, they're a hundred percent, if they weren't seeing friends, on Medal. Like that's where you have your memories because you're playing games together. It was a combination of Fortnite, TikTok, and COVID that really led to the platform blowing up

Turner: And you guys are still going.

Pim: Yeah. Yeah. We're still growing, despite COVID unwinding, which is nice.

Turner: That's kind of rare. I mean, there's a lot of people where the trends were just too hard against them that they couldn't fight through it.

Pim: The cool thing about Medal is that it's a really good single-player experience. So if you look at companies that ended up trending down, a lot of it was because they were very good multiplayer environments, but they were not good single-player environments. Because Medal is inherently that capture motivation – capture, edit, share – those are inherently single-player behaviors.

Instagram, by the way, Kevin Systrom said the same thing about Instagram before. Build a good single-player environment and figure out how to turn it into multiplayer environments. If you have only a multiplayer environment, naturally, when that network effects start shrinking, your platform dies.

Turner: It's like your liquidity of content posting, browsing, viewing.

Pim: Look at Facebook. The time it took Facebook to become irrelevant after the core people started leaving was very low. It wasn't a very long period because there was nothing interesting on Facebook anymore. And so, a few other platforms have the same problem post-COVID but we didn't because it is inherently a single-player behavior.

Now games do have that problem, which means we do see the aftermath. Because games that are inherently multiplayer, they are going to go through these network effects shrinking. But for the most part on those games, we saw them transition more into like a weekly habit as opposed to a daily habit. And then there's other games like Roblox that didn't have that problem.

Turner: And then you benefit from the ebbs and flows of different games. You're like a shock absorber. Maybe for a couple months, Valorant, Rocket League Minecraft are popular, but then Roblox takes some share and they're still on Medal and you benefit from gaming time spent as a whole.

Pim: Any mass consumer platform that has an organic go-to market, you can tie almost all of them to this thing called a social inflection point. Like Nextdoor is tied to when you buy a new house or move into a new neighborhood. Twitter and Telegram are both tied to major world events. Slack is tied to when you join or build a new project And so, Medal is tied to new games.

These are definitely inflection points for us. These are what drive all organic growth and they're very good for us.

Turner: Were you still doing all this on $150k or was there another point where you needed money?

Pim: We raised our seed round, I believe, in 2018.

Turner: Was that shortly after you launched?

Pim: Shortly after we launched Medal. Yes.

Turner: Nice. What was that process like? Was it a little bit easier?

Pim: Uh, no. Because we were splitting our focus. We hadn't decided to pivot yet. We were working on Medal but we were also still working on the game. So our story was pretty unclear. My first raise was actually pretty hard because we weren't really sure which one we were going to do. and as a company, we had been trying to raise for a long time, so it wasn't really working.

I think I have the sheet somewhere. It was like 87 meetings and one “Yes” that ended up doing it. And then that one “Yes,” ended up turning into obviously a lot more “Yes”es, but yeah, it was hard.

Why an Investor’s Belief in a Founder Matters

Turner: Do you know what was the thing people were buying into? Did they really like the thesis? Did they just really buy into you and the team?

Pim: In retrospect they've told us that they bought into us as a team, but at the time it definitely felt like they were pretty invested in the products that we were building. But I think that's normal for a founder. I think it's just an ego thing. I thought they liked the products, but they liked us.

Turner: It's really interesting, a lot of people have different opinions on this, and I try to form my own opinions, but it's always like, sometimes you're more influenced by the founder. You're like, “She's just going to figure something out,” or it's that the product's just so good. The founder's passion or intellect or drive is being reflected in how good the product is.

It's hard to really tie it down, but I think it does usually come back to just the founders. That's how you build a good product – it's through the team.

How Medal Used the Capital from Its Seed Round

Turner: Okay, so you raised a Seed round. What were you using the money for? Were you guys like doing a lot of customer acquisition? Was it hiring the team to build product? At what point then did you decide to kind of go all in on this clip thing?

Pim: Yeah, I mean we were trying a bunch of stuff. We obviously had to build a team because building a video platform is surprisingly hard. There's a lot to it, especially if you're trying to do a recorder, mobile app, website, desktop app.

Turner: What all did you try?

Pim: We started off as just a mobile app and then we built a recorder on PC. And then the recorder worked so we had to build a desktop app for the recorder. And then people wanted the mobile app to go along with their clips because they wanted to view their stuff when they were at school and show their friends. And we had to build a mobile app.

Eventually the mobile app became very popular for also viewing content, so then we initially built the mobile app in JavaScript. That was actually one of my projects. I made the mobile version and then eventually hired an engineer to maintain it, but then we decided to go native.

It was a very expensive and long company to build, to get to a really good product quality. That's what we used most of the money for. And then we tried paid user acquisition for two years and then we didn't need it anymore.

Turner: So in terms of all these different features you were adding, how did you know what to do? Were you just talking to users?

Pim: Talking to users and using the products, to be honest. It’s like playing games and then finding every little annoyance that you find and then fixing it. For us, if you think about it, taking a clip and sharing it really quickly is not that complicated of a use case. It’s something that you could very easily test yourself on a bunch of low-end devices and see if it works well. Most of it was just us using the product ourselves and then fixing it up and then shipping when we had updates.

Turner: Were there any times where you were like, “Holy shit, this works. Like this is actually a real company.”?

Pim: At some point we hit 10,000 videos captured per day, which. Right now we're at three and a half million. That was the big moment for us. It was like, “Whoa, people are capturing 10,000 of these moments.” And then they were uploading 5,000 of them or something.

We were like, “This is really – we are doing this.” We had pretty high conviction at that point. We were seeing good both organic and paid installs.

Turner: Were there any pieces that were breaking? Things that didn't work or holes you needed to plug?

Pim: Forr sure, I wrote the first version of the backend. At some point, queries were just timing out and we had to write a new version because mine was too scrappy, frankly. We had to hire a better backend engineer to build a better version of the backend.

The mobile app was written in JavaScript so we took a lot of the code from that and turned it into desktop app because we had the account system and all these things we had already built. And so the desktop app was like a copy and paste of the existing mobile app that we had, and then with a desktop functionality built around it, which initially was like a very bad architecture. We had to do a lot of things to get out of that.

They say that growth solves everything. And like, honestly, that's true. Unless your growth is unprofitable and it will eventually kill you, which you and I have seen, then it will actually solve all problems. As long as you're growing, it's easier to recruit, it's easier to find investors and get the best talent. That is really the main problem to solve. And we always did, which is really nice.

Turner: Talking about recruiting, I think you've mentioned before that every single employee you had at Soulsplit, your Runescape server, now works at Medal. Is that true?

Pim: It is – most of them, I wouldn't say it's every single one of them. all. The ones that we had the opportunity to work with, I would say it's like 60 to 80% of them. So definitely a majority. But when you like working with people, why not do it again?

My partner at my private server, Josh, is now CTO at Medal. We grew up together. I think, in a way, it was kind of interesting because at my private server, I was the person really calling the shots because it was mine. But this was the first time that we actually collaborated and did it together, which created a very different dynamic and has been really good.

So yeah, it's all the talent from the private server. We brought them in together to do this one and it has turned out great.

Favorite Interview Questions

Turner: Do you have a strategy for hiring or a favorite interview question that you look for in people?

Pim: I have a number of favorite interview questions. The first one I like is asking someone to explain how a system they work on works. Because it's super simple. It tells you a lot about the thing they take pride in and how much they actually learn about it.

Say somebody can tell me the different connections that are running in the network protocol, as if it was a game server. Why did you pick that protocol? What are the problems with it? If you can go to this level of granularity, I can tell you are the person.

Additionally, if while you are telling me about that high-level strategy, and I dig a little deeper about how these systems actually work and it gets a little iffy, I can tell you're usually using it to get ahead and it wasn't actually your work. That's why it's my favorite question.

This can range from “How did the website work?” to “How did the server work?” And then I'll ask a lot of clarifying questions to make sure I understand. Usually I get a good idea of 1) how technical the person is, 2) how ambitious they are, and 3) how deep they go. The deeper they go, the better, and also the things they work on.

I have a few things I look for. Like if somebody speaks ill of the people they used to work with in order to hide something they did. If they're trying to prevent you from talking to their former employers, I always look at that as a big red flag, as they don't take ownership of the mistakes.

I also always ask people to describe their mistakes and I always ask them what they could have done differently. How do you respond to that question? Even if they did nothing wrong, if you're a humble person and you don’t have massive ego, you can still respond to that question and say, “I encouraged us to work more as a team by facilitating more of these discussions”, for example.

Even if your team didn't work well together and it’s not just your fault, realistically there's always something you could have done better. Their response tells me how they're going to deal with failure. It tells me if they've run away from it.

For me, if something fails, I want to know everything about it. I am obsessed with why things either work or don't work in this world. A failure is an opportunity to regroup, rephrase, modify, edit, keep going. There's people who look at that and they get discouraged, and that's fine too. How they deal with this question tells me a lot about the person.

This is controversial, but I generally look very negatively at people with very short work stints. Startups are hard, projects are hard, people are hard. And I'm not going to invest my time in somebody who I think is going to leave at the first sign of trouble.

Turner: Or not be invested in you and Medal. You want it to be a mutual investment.

Pim: It's not even about that for me because I could really mess up, right? We're really far along now, but hypothetically three years ago, we could have chosen to pivot. I don't care about that.

I care about if you are obsessed with building for people. I care that you are able to take a few hits and build that personal environment where you can take those hits and at the same time, you're not someone that jumps to the next shiny object.

And that's hard because people pay a lot in tech. And so this is something that people do, and I get it. If that's your style, that's your style, but that does mean I'm probably not going to hire you. I'm looking for people who are builders who want to learn how to build things, people who want to be part of one of the most unique groups of people I have ever worked with.

And sure, eventually, after we raised our B and C, that meant we're going to obviously also pay you a lot of money, but initially that wasn't possible. So I had to look for those things.

Why Remote Work Was a Big Mistake

Turner: So you had a really interesting point about talking about mistakes. What do you think was the biggest thing you messed up with Medal? Like anything you would change if you could go back?

Pim: The biggest mistake I made was overreacting to remote work and moving everybody remote after we had built an amazing in-person culture. If I look at the most destructive thing I've ever done, that's it.

Turner: Can you talk us through that?

Pim: For remote environments, it's hard when work environments are different or unique. Because in the end, it's about your connection with people and the problems you're solving together. If you're isolated, the job is just a job. What I found is that remotely, the company started feeling to people like just a job.

The second mistake I made is that I didn't keep the bar high enough for a while, I think. So as a result of that being the accepted culture, my thinking was, “There's a mass pandemic going on. There was a lot of political uncertainty.” And so I was like, “People are burned out, so this is going to fly over.” And I ended up lowering it a little bit because hiring was so hard. That's probably the second biggest mistake.

You might see them as one, but I think the second is that during COVID, while we were remote, because we wanted to hire, we overhired and we hired people that didn't meet those criteria. We ended up shifting the company back in-person, which was painful. We lost a lot of people. But I have seen that culture is back.

I will say that probably put the company back. I don't even think it was legal to stay in-person. But we should have gone back to the office sooner. And we should have spent more time together. And we probably shouldn't have lowered the bar during COVID just to be able to hire people. We should have stayed a little bit smaller for a little bit longer.

We grew to almost 105 people, I believe. And now we're about 45, for context. We are generating more revenue and have more users than we did during COVID. If you're optimizing for a team, you're optimizing for density.

If you find somebody that doesn't meet the criteria, I've adapted this thing that I overheard from another entrepreneur that said, “In our culture, if it's not a hell yes, it's a no”, which makes it very easy to say no to things. I've really adapted that culture, in hiring and everything. But if it's not a hell yes, it's a no.

Medal’s Approach to In-Person Work and Building Culture

Turner: And you had quite a few employees in Europe. You were saying, we're going to move in-person in New York.

Pim: Our version of in-person is different than other companies, I would say. So before COVID, we were about 75% in-person. My first company, I built 100% remotely. Decision-making was very centralized.

I think how remote a company can be is directly correlated to the amount of people involved in the decision making process. The people making decisions need to be in the same room. If you are a people manager, you have to be in-person, no exceptions. And you're in the office five days a week.

If you are an IC[2], you're allowed to be remote at Medal, but you're spending 10 business days out of every eight weeks in the office. That's per team. So as a team, you can choose to come in on a Monday, work through the weekend, and leave the next week. Or you can spend time in New York on the weekend, do stuff together, and then work again the next week. Usually it's a mix, so you have to spend 10 business days every eight weeks, if you're an IC.

This is good because it keeps the culture. Eight weeks is the perfect period to keep that culture ingrained. And if you’re a decision-maker, you have to be in-person. It really helps us filter out the people who just want to write code and get stuff done versus the people that want to become leaders.

We had this dense culture of leaders and constantly ICs rotating in and out. And as leaders it's cool because you're constantly spending time with new teams.

[2] IC stands for independent contractor. Independent contractors typically set their own hours, scope and other aspects of their work and can serve multiple businesses. They generally don’t receive employment benefits such as paid time off or insurance coverage.

Turner: You mean you switch what team you're on inside of Medal?

Pim: No, they fly in. So they're 10 business days and they're never there all at the same time. So every 10 days there's a different team in New York. For the leaders it feels like 100% in-person.

At the same time, if there are ICs, they just want to get stuff done, they can do that. They can spend six weeks getting stuff done, 10 days in the office with us, making sure the stuff they're working on is the right thing.

A large part of those ICs’ motivations is having those personal conversations, being close to the decision-makers, and doing things together. They want to trust decision-makers. And if you don't talk to each other, you don't trust each other.

This has been our structure for almost a year now. Our culture is better than it was before COVID, because we made a commitment to spending time in-person. The truth is that we had tried every other thing.

We tried career ladders, bringing in excellent VPs from top companies. We tried semi-annual retreats together. We literally tried everything to the point where we were like “The problem is remote.” This was before everyone started realizing this.

In 2022, we started moving into spending more time in-person. And then we pulled the plug on New York because we had people from Europe who work at Medal. We were all in LA but many from Europe moved back and New York is the place most accessible from Europe for traveling because it’s a short flight compared to SF or LA.

Turner: For the management team, for those more senior, it's 100% in-person, but if you're more of an IC, it's 75% remote but you still spend a lot of time in-person?

Pim: The two weeks are intense. It's 75%, but we think it's more like 60/40.

Turner: So you describe it as in-person, but you're hybrid. It seems like you found a sweet spot.

Pim: The amount of impact someone has at a company isn't a one to ten scale. It's a one to a thousand scale, maybe even minus one thousand to a thousand scale. In a remote environment, where someone starts is where they'll likely stay.

So let’s say you’re a +100. You're probably gonna stay at a plus 100. You're maybe gonna become a +150 because you're gonna work a little faster. You might become a +180 because you get a little better. But in person, when you're constantly observing those founders who are at +700, +800 – it's contagious. People go from 0 to 500 quicker.

In remote, if you are a nine out of ten performer you’re already at a point where you don’t need that. The amount of people I'm talking about remote is like 20. We've picked the people that are allowed to operate in this structure and it's unlikely we'll hire new people into it.

We hire in-person, we don't hire remotely, which is why I describe it as an in-person culture. But we do have this structure for those who couldn't come to New York.

Turner: We went deep on remote work during COVID. You raised a couple rounds during COVID. You raised the seed round, then the Series A. Was that when it was working, you had 10,000 clips a day?

Pim: It was a hundred thousand clips a day.

Why Medal’s Series A was Easy to Raise

Turner: So, did you feel the need to generate more revenue just to cover the bills? How did that process play out?

Pim: Our seed round was challenging. By our Series A, we had become proficient at fundraising. We conducted our Series A meetings at the Game Developer Conference (GDC) in 2019.

Turner: Was GDC a gaming event?

Pim: Yes, it's the largest gaming conference of the year.

Turner: All the investors were there?

Pim: Correct. And so we lined up all the meetings at GDC. Josh and I sprinted from meeting to meeting, but we had them lined up, because the metrics were good. We did back-to-back meetings and ended up getting two term sheets at GDC, one of which we accepted and were very happy with.

The Series A was, fairly easy. Series B we raised right when Covid broke out because I was actually very concerned about the market. The series B was mostly like insiders. The company was doing really well. And I didn’t know what would happen with COVID, like the market crashed, right?

Also for context, I had worked at Doctors Without Borders on Ebola before starting Medal. So my idea of what could happen here was pretty grim. And I think I probably overreacted a bit. We raised a series B while things were going extremely well.

Turner: That's a good time to raise though. It's good to raise when you look like a good investment.

PIM: Yeah, and luckily we had Makers Fund on the cap table for us. They weren't a major stakeholder before, but they really liked us and so they bought a bunch more of the company at Series B, which was great even though they're not traditionally a Series B fund.

It was unusual times. They did the Series B, and then we raised the Series C from OMERS in late 2021 and also Dune, and then the rest was internal as well. We basically had a one year in between every fundraise up until about late 2021.

Two things happened after that, which is valuations reset obviously. It wasn’t a great time to raise. And also we turned on revenue. We were in the process of turning on revenue and we knew that we were going to be valued on revenue moving forward.

So were doing the very typical consumer growth play where you have good retention and you have good organic growth. You don't spend money in marketing. You assume you can make money, but we weren't sure. The other thing is that because we're video, it's traditionally easy to monetize. Very engaging.

We wanted to push it off monetization because the market was very competitive. We spent most of 2021 buying companies and building the good product together. So 2021 was really interesting. We raised our last round in late 2021. And then, 2022 was like a reset for us.

We reset the culture back to in-person and then 2023 for us has been growing again. Like we're basically turning that growth into precision work where we know exactly what we're doing, having a culture that we love, having a product that is working, and also now monetizing really well.

And then figuring out, how do you get that to scale as quickly as possible. We’re very much in the scaling phases now and like less so in the figuring stuff out, which is really nice.

Turner: Can you talk much about the monetization? I guess I have a couple ideas in my head about how you might be making money.

Pim: It's very easy. It's subscriptions.

Turner: What do people pay for? What are you giving them when they subscribe?

Pim: It’s $9.99 a month. You can go from uploads that are two minutes to uploads that are 10 minutes. You can download videos without the Medal watermark on them. We give you status symbols around your profile when you're using the product so your background on your profile is gold. Your activity shows up gold in the background.

It's a kind of a combination of the profile status play and utility, and that's going really well. So revenue went live July of 2022 and I believe it's grown, on average, between 50 and 25% per month since then. Basically, we're now at the point where we're pretty close to being profitable just off subscriptions. We haven't even launched creator monetization. We haven't even launched ads.

Turner: David at Dune told me that I had to ask you this question. You didn't have a deck or there was something crazy in either your Series A or Series B deck. Does that ring a bell? Do you know what I'm talking about?

Pim: Yeah. But the context here – I believe it was probably the Series B where we didn't have a deck because 1) we were growing really fast, 2) it was COVID, 3) we already had a lead because Makers already knew they liked the company, and 4) I’m extremely consistent with investor updates.

You can literally go back every month and read what's going on with the company. My investors, they knew what was going on, so they were ready to commit. I’ve done two rounds without a deck. The Series A+, which was basically after we got our Series A locked in, there were a bunch of people that wanted exposure to the company, that we couldn't fit into the A. I didn't take their money at first because I didn't have a way to use it. And then once we started ramping up paid, for a little bit at the end of 2019, we decided that we were gonna take that money and put it into paid advertising.

It was people that had already seen the company that I said no to, and later I went back to and said yes. So there was a round that I raised off an email that was $3.6 million. That was my Series A+. We raised $7.5 in the A and then we did one maybe like three to six months later, which was pretty cool. It was an uncapped note. It was crazy.

Turner: Yeah, it’s a disaster for most investors, but…

Pim: No but the cool thing is they did really well because the note ended up converting right when COVID broke out, so it wasn't too far off. That was the other round that didn't have a deck, which is where David came in, because we were already quite consistent.

I know it's a bit of a meme to raise around without a deck, but again, I stand by that. This whole business is all about building trust and maintaining relationships and doing what you say you're gonna do.

Turner: He said the deck included a potato house. What does that even mean?

Pim: Okay, so there was a strategy appendix. This was not a fundraising deck. There were people who were interested in the Series B that I had sent an 10 to 15 slides of my thoughts on the business strategy that they had asked for.

I built this deck that was like, “Instagram for games has been tried a thousand times. What you care about is somebody who's sharing these memories. It's first and foremost your own moments before anyone else's.” On Instagram and Snapchat, I would argue that their biggest secret is that people care far more about their own stuff than they care about everyone else's. As a product person, that's where you invest, right?

We saw the same thing. And so what everybody was doing is they were building these network-like companies that were like, “Upload your video clip.” And we were like, “No, you gotta go deeply personal by building the capture layer and then expanding from there.”

So the potato was there because my argument was, “This has been tried a bunch of times. Here are the examples. Here's the competition. I can find more efficient ways to light money on fire. Did you know they made house out of potatoes?” and yes, there was a picture of it as well.

It was kind of a meme-y way of like saying “This strategy doesn't work. We're gonna do something better.” It made for a memorable deck for sure. I can send it to you after.

(The potato house slide from Medal’s deck)

Turner: And you mentioned you, you had a bunch of slides about strategy, how much do you share? I know some people, if they’re pretty early, they don't want to tell you their vision for the company. Isit a good idea to share exactly what you wanna build with investors?

Pim: The amount of people that can actually do things in this world and make a vision come true are far more limited than we imagine. The majority of people, frankly, are not occupied with what you're doing. That’s the big myth.

There are people that will copy you, don't get me wrong, but in the end, if it's that easy to just copy you, they'll do that anyways. So the way that I'm looking at it is, everything that you do in startups, it comes down to your own speed and your own merit. And if you're comfortable with your own speed and your own merit and you know you're better than the people you're competing with, then by all means go shout it.

If you don't think that anyone can do what you're doing and do it better, then share it. We were already at a point where we realized it was pretty difficult for competitors to go build what we were building. In fact, a lot of them had tried and failed and so we kind of knew that we were kind of the favorites to win this particular segment of the market already.

Turner: And this was the Series B, where you had hit like a certain amount of scale?

Pim: It was when we turned off paid user acquisition and the company was still growing more than 10% a month. That's when we kind of knew that things were just really working. There were a bunch of companies that still tried to go out after this space after that still got funding and most of them are either doing adjacent stuff, or a lot of them are pretty interesting.

They're focusing on TikTok capture now. That same problem that I described to you, which is that basically a lot of the recording software was built for long-form recording as opposed to short-form recording. All that is true for live-streaming software still.

There’s now like things like Medal that you can have good short-form recording, but long-form recording from live streams and turning that into short-form is still really difficult. A lot of competitors are now in that space, which is really interesting. Our competition is mostly coming from the larger companies now.

Actually what's funny is, you kind of go from fearing your competitors to fearing your users, which is even more scary. Because when there's nobody in the space really chasing you. It's very hard to get that same level of urgency behind a lot of the things that you're doing until you look at your retention data when people hit certain paths on the product where they just quit.

You kind of go from worrying about your competitors to really worrying about the problems that you have with your own product and the users. It's very refreshing. I think the lesson there is that actually we probably should have cared less about competitors and more about those problems in the first few years. I think there was probably at least a year that we spent too much time worrying about competition. That's probably my, third biggest mistake.

Turner: What are examples of maybe places where you didn't focus enough on the customer or you lost people because you didn't listen to them enough?

Pim: Doing video capture is incredibly difficult. Every PC has different hardware, different versions of the operating system, different encoders, GPU encoding, CPU encoding, integrated GPU or not… It has to work perfectly with all these things: webcam enabled, webcam not enabled, game that you're allowed to inject into to capture the frames versus you have to capture the screen.

There are all these variations under which the software has to work really well. And I think for a good period of time, we care too much about the network and too little about like the edge 10% of use cases that needed to be supported.

For example you think about it, if you're growing 10% less for a year every single month, that compounds to a lot less than what you could have been. And so I think the lesson there is that I was probably too fast in a lot of the network decisions and too slow in a lot of the core product quality decisions. It didn't lead to us losing our position in the market. We were always quite careful with it, but we could have made more people happy faster if we switched that priority a little sooner.

Turner: So what would that have been? Because I guess when I think about what's like the common advice, there's the Pareto principle. It's like listen to the 20% of people that drive 80% of the outcomes. Some people might say screw the 10% that you're not hitting. Why was that important?

Pim: I take feedback on the product very personally, and maybe that's just me. Here’s the thing: Medal was my first product that went beyond 10 million people. And so, I've never tried running product the other way. It's too risky for me because I know this thing is working.

So I fear that the feedback that my users are giving me and the potential size of those problems, because I'm pretty good at quantifying product problems when they're presented. It’s always hard to take a like non-quantified thing and weigh it against a very quantified problem. It’s easy to look at it like a failure.

In retrospect, I think we could have done both better, but I think the outcome is that social graph and social growth and content consumption started growing like crazy. At the same time, we have a lot of users now that, for example, have specific problems where we now have like a year worth of quarter backlog that we have to go and solve.

I think if I had done it again and knowing what would've worked, I would've spent a lot less time chasing high upside social graph in the fear of the competitor coming and wiping us out, and spend more time on those 10% of recorder people, because that's your baseline. We did good, but we could have done better

Turner: So how do you think about iterating on product?

Pim: The main thing I would add there on how you iterate on product is rapid fire iteration – your speed is everything. And you have nothing until you have retention. Don’t let anybody convince you of anything until you have, if you're a network, more than 20% Day 30 retention on the 30th day. You just iterate until then, and then everything works itself out if you manage to figure out how to grow as well. Iteration is speed and if you're not shipping every day, then it's probably problematic.

Turner: What's kind of the state of Medal now? I don't know if I've ever like seen. How big are you guys? Publicly, what are you saying?

Pim: Yeah, so we have DAU and MAU at single digit millions at the moment, but growing at a very consistently same pace since COVID. And as of the last 6 to 12 months, we've really been able to start building that on-platform social graph, on-content graph so that the use case has become more social sharing versus the capture components.

In addition to that, revenue is obviously working so our state is basically we have this base engine that's working really well. Now we're trying to take that into Latin America and Japan and try to figure out how we can replicate that success to get even faster growth. We have this like baseline engine that's growing steadily in Europe and the US. And now we're trying to figure out, can we plant that in Brazil? Can we plant that in Japan? Et cetera.

Turner: And you've gone from kind of this tool to a little bit more and more of a destination that people will visit. It just unlocks more on the business model too, of what all you can do.

Pim: Yeah. We have this interesting trend, which is kind of like, if you think about what I said at the beginning, that feeds are less engaging than interactive entertainment. What we are seeing, however, is that people are starting to watch more than they play. but that's not necessarily TikTok feeds. A lot of those are on YouTube and we see it in our own data as well.

A lot of time, if your friends are playing, for example, that's still interactive and fun so you'll watch your friend play. What we've seen is that a lot of that trend in the past year is that we're going from a lot of play to a lot of watch, which has been really interesting.

Turner: So you guys have acquired, I think you said six companies. How do you acquire a company? What's the process like? If I'm a founder trying to think about it, what should I be thinking about?

Pim: Each of them is different. The most straightforward ones are the ones where you need the tech that they have. So we did two acquisitions, which was the PC editor and the mobile editor, which were just straight up, we had a very clear goal. This is how much we're willing to pay and then generally you kind of wait for a point where that company is interested.

Turner: You're kind of paying for R&D or you would've had to hire these people to build, which would have taken time.

Pim: And once you get a product at scale, you realize that actually going zero to one on things is really hard. It’s actually much less risky to buy something that has gone from zero to one, and maybe found like mediocre success that you can improve than try to figure everything out on your own.

We did that with the PC editor and we did that with the mobile editor as well. Those were both technical acquisitions. We did another technical acquisition, which was cloud clipping, which is where you basically generate the video inside the cloud. This was also an R&D acquisition – we bought the best company at that so that we could go and integrate it into the product.

That was Gif Your Game. It was less clear, it was more future vision. The first two were like, “We have a problem, we can quantify how much we would pay for it on like time and we'll spend the money or not. Plus we get a good, really good team that is passionate about this space.”

We also used the fact that we had raised our Series C, which kind of cemented our position in the markets, and our growth where most of these other companies weren't growing anymore. We kind of used that to get a lot of those companies on board with us so that they would retain upside in the market, which I spent like four to five years building in. And they could go do something else. Three of those companies were kind of that caliber.

Turner: So you would give them equity in Medal and then they would not have to keep working and they could go?

Pim: Correct. Three of our acquisitions were founders who deeply believed in the space, who we competed with before, who saw that we were very successful and decided that they wanted to join up with us as opposed to continue to compete against us.

There’s Fuse, and to an extent, there's actually one that we haven't announced. It happened years ago, but they wanted to keep it quiet. Those are easy because like you don't have to spend a ton of cash because the founders want to stay long. As long as the investors are okay with that, they kind of shift their interests to a different asset and that worked really well for us.

We’ve done a few cash deals that were primarily for talent. Obviously you give the talent equity, but you gotta buy out the cap table. So we've done a few of those. Every single one of my acquisitions has been strategic to where I want that to be a part of the product order roadmap at some point.

It's just that level of clarity was very clear on some and not very clear on others. Right. Like Megacool, for example, is the B2B clipping. We knew that it would be five years before we got to it, right? But the team was really good. So it's primarily an acquihire. And then we knew that the product would become useful and the knowledge would become useful.

Gif Your Game – same thing, two to three years into the future, but the talent was really good. Team was really good. Fuse and this other company that I can't talk about fit in right then and there. We just have to go do it. What I learned is you have to be okay whether or not that acquisition is successful or not because they take time. And so the speed of close is really important to your entire org because they need clarity. Are you gonna build the thing or are we gonna buy the thing?

Look at Microsoft, Activision – I cannot imagine how hard that was for the people making decisions there, right? Because you either have this thing or you don't.

Turner: How long did that play out?

Pim: I think it's over a year now.

Turner: Okay. And is it like officially closed? Didn't it get like approved or something?

Pim: Yeah, so I believe they are allowed to close before October 18th or something like that. I think the major hurdle hurdles are probably over, but that just gives you an idea. You gotta do 'em quick.

That’s the other thing that I learned. Good deals happen quickly or not at all. You don't have velocity behind the process? It's gonna fail. You have to see eye to eye with the founders, obviously. Like if it's already like a combative process during the negotiation, it's just not gonna work unless you have like a billion-dollar proven business and you buy another billion-dollar proven business.

That’s a different story because you're built. You're buying a system, not team and a product. And then each of the acquisitions just have their own nuances. And again, for me, everything comes down to relationships.

The thing that I think did really well is that I'm still close with most of the founders that we acquire companies from, and I could call them anytime and ask them a question. And they would help. I think the, the people aspect is very important.

Turner: Do you spend time getting to know your competitors? Even if it's just like a friendly, like, “Hey, we should probably just know each other.”

Pim: Yeah. So Fuse and Gif Your Game, which, which were two of our competitors, we bought both these companies on the same day. We shook hands on terms on the same day. They didn't know.

Turner: Oh, interesting. Okay.

Pim: I had dinner with the founder of Gif Your Game. And then at 7:00 PM the founder of Fuse texted me that he was interested in selling, and I went to his house. They’re both in LA so dinner was in Santa Monica with the founder of Gif Your Game. We were already talking, they already knew, so we agreed on terms with them. And then, I got the text. It was crazy. I told my team about it and I went and shook hands on the terms for Fuse at like 10:00 PM that night.

And the reason was because I already knew these people. They knew they could text me. I had never really like positioned myself as this combative force. I was always kind of there if they needed me in a good way. I wouldn't speak ill of them. I wouldn't make life difficult for them.

We respected each other because we competed. That’s the other thing that I learned is that you respect your competitors. I'm good friends with a lot of people that I've competed with in the past.

Turner: And I think for the audience too, they might not know I invested in a competitor of Medal before I met him. And, we're just friends now. I feel like there's a lot to learn too from competitors also. And again, they might pivot also, and then maybe you guys are like allies down the road or you team up and you work together. I feel like there are a lot of ways to approach it.

Pim: I think a competitor relationship is just another relationship. It's just like the timing isn't right, you know?

Turner: Yeah. And truly at the end of the day, if you both become a sustainable business, you have different customers probably. So maybe you compete adjacent in a way. But you're still serving probably different customer segments or one of you won't exist eventually,

Pim: As long as you stay like above the belt, product development and getting things adopted by people is as much of a meritocracy as it should be. You are judged entirely on your results and not in your efforts, which is like the ultimate game, in my opinion.

And so that's the thing about competition, right? If they can beat you, it's because you're not good enough. Let's just face it. And. you know, that's a very absolute take, but that's the truth. If you are not good enough, it means you have to fix something.

Competitors are good because they keep you on your toes. Again, there are things that you can do that are below the belt that, you likely won't have a relationship, but I mean, most companies don't do that.

Turner: Alright, let's jump into rapid fire. So do you have a favorite CEO that you really look up to or that you've learned a lot from?

Pim: Elon Musk. Pre 2023.

Turner: Okay. So this was before he went down this interesting path with Twitter.

Pim: Okay. It went from real interesting and relatable to real interesting, but less relatable real quick. And I think his style is very, very interesting. Let me put it this way. I really liked everything he did up until the point where he started messing with the things that I knew a lot about.

I knew they were the wrong decisions, which is when I started thinking that there were maybe a few weaknesses to his approach as well. I admire everything he did. But there were a few things that he did in 2023, and when it comes to people and when it comes to products, I know taking a slower approach is better.

He would still probably be my number one pick if it was like a CEO I looked up to, but I wish he slowed down a little bit sometimes.

Turner: Do you like his like, commitment, passion, vision?

Pim: Dedication to the mission. Willingness to get into weeds. Not being afraid of being contrarian and people-pleasing or caring about optics. What he did with Twitter really was the beginning of like a great reset in tech when it comes to, expectations and work ethic frankly.

The thing that I really like about him is that he leads with big missions. which allows people to buy into big missions and solve big problems despite him not necessarily being there for everything. And so I think leading with a big mission is just really, really important.

If you're gonna do a big company – he did this with Tesla and Neuraliunk and Boring – there's just a playbook that is like very respectable to me. The means of executing it sometimes have question marks, but the basis I really respect.

Turner: Favorite game? What are you playing right now?

Pim: Rocket League.

Turner: Rock League. I feel like you've played that for a long time.

Pim: It is one of those games where I got to a place in the ranked letters that I'm just so consumed by it. No other game comes close in terms of how it engages me.

Turner: Just to explain Rocket League super quickly for people, it's soccer, but you have a car that you control instead of a person.

Pim: Yeah but it goes really deep.

Turner: And the physics are very interesting, right? The way it all bounces and moves. And it's an enclosed course and you can drive up the sides

Pim: Yeah, exactly. There is so much to it. It's such a simple game, but there's so much depth to the mechanics and play styles that I could play for a very long time. It gets very tiring because it’s a very high pace but it's amazing.

Turner: Awesome. Well, speaking of amazing. This was a great conversation. Thanks for coming on. Hopefully people learned something. I feel like we went deep on a lot of interesting topics.

Stream the full episode on Apple, Spotify, or YouTube.

Find transcripts of all other episodes here.