🎧🍌 Building a $70 Million Chocolate Factory | Nick Saltarelli (Co-founder, Mid-Day Squares)

Competing with 100+ year old monopolies, surviving a 85% drop in revenue, building a moat in CPG, lessons from Facebook's launch strategy, and why founding teams should go to therapy

👉 Stream on Apple, Spotify, and YouTube

Nick Saltarelli is the Co-founder of Mid-Day Squares, a healthy, functional chocolate bar. Nick, his wife Lezlie, and her brother Jake started the company in 2018 from their kitchen in Montreal, and have since built their own factory with $70 million in capacity, and grown the company to a $26 million revenue run rate.

Find Nick on Twitter and LinkedIn.

The episode is brought to you by Secureframe

Secureframe is the automated compliance platform built by compliance experts.

Thousands of customers like Ramp, AngelList, and Coda trust Secureframe to get and stay compliant with security and privacy frameworks like SOC 2, ISO 27001, HIPAA, PCI, GDPR, and more.

Use Secureframe to automate your compliance process, focus on your customers, and close deals + grow your revenue faster.

To inquire on sponsorship opportunities for future episodes, click here.

In this episode, we discuss:

The history of the $200 billion chocolate market

Competing against 100+ year old monopolies

Finding a huge opportunity in healthier chocolate

The dirty secrets of contact manufacturing

Why no one knows how to make a Snickers bar and Coca Cola doesn't have a patent

How to build a moat in CPG

The reason Mid-Day Squares had to build their own factory

Making chocolate like Tesla makes cars

Copying Facebook’s launch strategy

Measuring product market fit in CPG

Almost running out of money during COVID

Why every founding team should go to therapy

Surviving a 85% drop in revenue

How to raise a bridge round

Building an enduring brand

Why marketers should study the music industry

Follow The Peel on Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok.

Thanks to Zac and Xavier at Supermix for the help with production and distribution!

Transcript

Find transcripts of all prior episodes here.

Turner: Nick, how's it going? Thanks for joining me today.

Nick: I'm pumped. Let's fire it up!

Turner: Can you just talk about the chocolate market? Help us understand everything that's going on, how big it is, what are the dynamics, all that stuff.

Nick: To set the stage, this is an industry that's caused war, that's caused corporate espionage. It's had largely three companies, maybe four, run it for the last 100 years. It's $142 billion industry. And anytime you have that amount of concentration of control with that much, let's call it treasure up for grabs, you're going to have a wild part of an industry.

So I would say Midday Squares has been trying to learn the politics of chocolate. Trying to make friends, trying to play the game rather than just sit here and complain that the game's hard to play.

We've had cease and desist thrown at us. We're still not allowed to call squares “functional chocolate,” like those two words are not allowed. At some points we even were questioning calling ourselves real chocolate, because we don't use dairy inside of our product and we don't use regular sugar inside of our product. We use like a coconut sugar, but there's no definition for coconut sugar.

Turner: You kind of market it as a healthy product, right? There's a reason that you don't.

Nick: It's absolutely a healthy product. Number one, it does not raise any of your blood sugar levels. It's under 160 calories per snack, under 10 grams of sugar. We don't use any artificial sugar, so we just use regular sugars, but we do it at a low threshold and we make a product that tastes good.

But like I told you, when you're entering an industry and you're pushing the status quo, you're going to be put in situations where you have to fight. And we've been in three of those situations already – one being a cease and desist from Hershey's that I'm proud about how we handled ourselves and how we came out.

But this is one of the craziest games in the world. It's a hundred years of four companies running the show. You're not going to just walk onto the stage claim your spot.

Turner: Okay, so that's not what I was expecting you to say. A hundred-year wars for companies. How did this all happen? Do you know the story around like market dynamics?

Nick: Europe was a huge component of the rise of chocolate. I read the Ferrero book and I think that, does a good job at explaining the history of chocolate. You have to remember, this was a sought after commodity. I won't go into the exact histories, not to botch it, but this was a treat that's been used for as long as probably modern civilization.

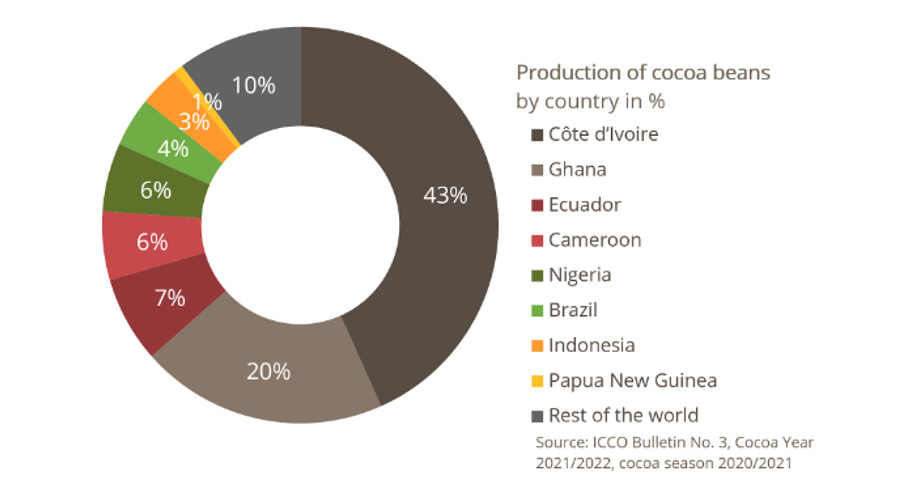

It's had many different formats along the way, from health aspects back in the day from the concentrated cocoa beans to the modern day confectionary snack. The cocoa bean can't be grown everywhere in the world. We can't grow it in North America. So that right there set the stage for a lot of problems in the cocoa trade in general, because most of the stuff's coming from Africa.

Most of it's now coming from South America, but still Africa's the dominant one. And I don't like getting into the war component, but everybody that knows anything about Africa knows that England pretty much controls most of the exports of Africa. And with that commodity has come a large lineage of problems which has caused chocolatiers to have to be very creative.

(Most cocoa is produced in Africa and South America. Source.)

That's really how Nutella was born. It was the rising price of the cocoa bean commodity and the introduction of a cheaper alternative through hazelnut. But nonetheless, this is a commodity that's had everything from modern-day slavery attached to it, child labor, all sorts of stuff that make dealing with this commodity intense.

And I think the average human doesn't understand what goes into commodities in general. I was just speaking with one of the biggest pineapple importers, and I'll leave their name out. They have a full militia. So this is a company that you guys know that is traded on a stock exchange in employment of a full militia that protects the jungle yards of their pineapples.

Turner: Wow.

Nick: They finance an internal army and this is how intense it goes. We could sit here and talk about these things all day and here we are just a small little player that started in 2018 making chocolate out of their condo, trying to navigate this whole thing.

Turner: Yeah, I definitely want to hear more about that. You guys also have your own factory, which I definitely want to talk about in a little. So it's a, $142 billion market. That's like revenue for the four big kind of conglomerates?

Nick: No, that's really the trade. If we're getting into market cap, if you just look at the four big conglomerates, it goes above $200 billion. We're talking $142 billion in revenue traded annually on the commodity.

Turner: Okay. $142 billion of the chocolate like cocoa?

Nick: No less cocoa commodity, really just chocolate. So that could be anything from the chocolate you dip your ice cream in, to chocolate at Halloween to chocolate that you get in a box to snacking chocolate like us. The full spectrum of chocolate.

Turner: Interesting.

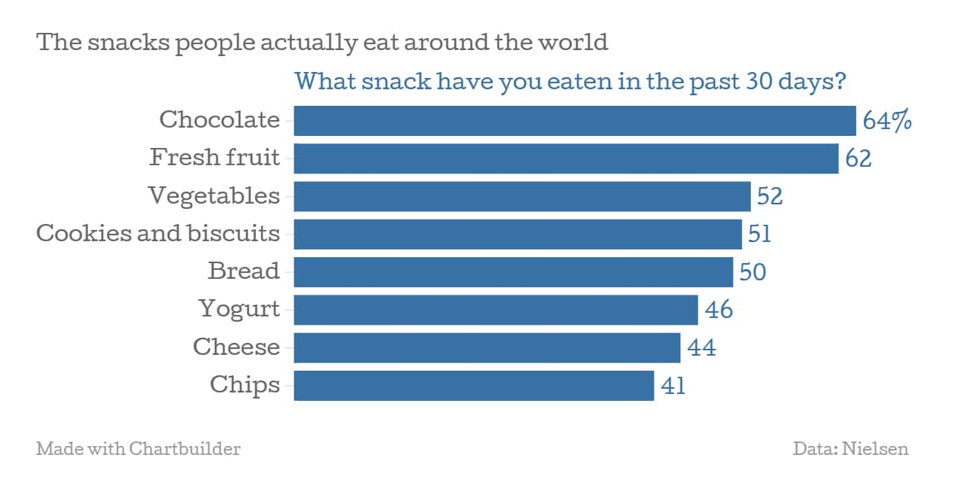

Nick: It's one of the largest snacked items after chips in the world. I believe it has actually even surpassed it on a global stage. And what's really interesting about chocolate and why we chose it, it requires no education in any country.

(Chocolate is the most popular snack in the world. Source.)

Every single country in the world, no matter where you are, if you give somebody a piece of chocolate in any form and condition, they know exactly what you're giving them for. They know it's a form of endearment. They know it's like a good vibe thing. It's an incredible market.

Turner: Do you know why it's so popular? It just, it tastes good. Is it cheap to produce and you can sell it at a high price?

Nick: Definitely not cheap. I think it goes back to our heritage and the globalization of the people. Again, not knowing the exact origins of chocolate, but you gotta remember this thing has been eaten for as long as modern humans have existed, and so spread naturally throughout the world.

Europe was the heartland of chocolate and chocolate consumption, but it has spread everywhere by this point. And I just think because it's a delicious thing. There's nothing quite like it. It's a fat that goes into your mouth and melts at this specific rate that just creates this incredible silk texture that just can't really be reproduced.

The most current form of recreating that mouthfeel was palm kernel oil. But I think prior to that there was no real substitute for chocolate. If you want a chocolate, you really just had to have it.

Turner: And it's so good to your point. It's probably one of the things I try to practice the most self-constraint with to prevent myself from only eating chocolate every day, for every meal.

Nick: That's why I got into the business. I was that kid. I think if you asked in my elementary school, I said I wanted to be Willy Wonka when I grow up. I used to watch commercials of Nestle run where, I don't know if you guys had this where you were, the rabbit for the cocoa would run around touching things and everything would turn to chocolate. That was my dream.

Turner: Was that Nesquik?

Nick: Yeah. Those were the Nesquik commercials and they were the best.

Turner: So you grew up in Montreal, right?

Nick: Yeah.

Turner: Okay. I grew up in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Nick: I didn't even know you were a fellow Canadian.

Turner: I am a fellow Canadian. I think those Nesquik commercials were a Canadian specific thing. Someone can probably correct us.

Nick: I do believe they were.

Turner: I remember those, the rabbit was so cool. The commercials were so much fun.

Nick: Yeah, and then the last piece just on the chocolate is because the melting point of cocoa fat is the temperature inside your mouth, that's what makes it such an incredible experience. When it's in the real world, it's kind of like this hard thing. And then the second it goes into your mouth, the melting point hits right away and it's just incredible texture.

Turner: And chocolate or at least mass-produced chocolate is probably not the most healthy for you.

Nick: Yeah, confectionary chocolate is like the furthest thing from being healthy.

Turner: So what does that mean? Confectionary chocolate? Can you kind of explain that to us and why it's not healthy?

Nick: Yeah I’m really pro business and pro everybody, so I'm not going to throw any one specific person under the bus. I'll just keep it general in the explanation. Most modern chocolate bars that you eat contain pretty much only sugar and palm kernel oil. The rest is, we're talking like micro percentages, very low percentages of cocoa.

Turner: So it's like fake chocolate basically.

Nick: Essentially it's not chocolate at all in those terms. And that really happened because the commodity of cocoa has gone up significantly in price. And what's better than selling sugar and fat? Nobody's going to say no to sugar and fat.

That being said, we're making a huge bet that palates are changing. And to be honest the product we're putting forward we think is where the modern consumer is going. And so you're absolutely right that the chocolate bars that you are eating today consist primarily of sugar and spike your blood sugar levels significantly. And that's why you, you feel kind of a crash and not great after eating them.

Turner: So this is a question from Twitter: are there any products that could be a threat to chocolate consumption? Are there any alternatives – or maybe Midday Square is the alternative – to what's currently called chocolate.

Nick: So I don't think at this current moment, there's a, like a threat to the actual chocolate piece of the industry. I think snacking diversification is probably the largest threat, right?

More and more snacks being introduced, people's palates and exploration, expanding well past just a chocolate snack as their go-to item. But based on the data we see chocolate is not going anywhere. And at least not in my lifetime, I don't believe.

Turner: Yeah, and I think I've seen just broadly, you probably read more about this stuff than I do, but any sort of healthy food option, all the numbers are growing whatever, double-digit percents, whether it's being plant-based, low sugar, dairy free, whatever it is, not just in chocolate but across most of food, it seems.

Nick: Here's the fun fact. If you go look at any of the snacking items that exist in the US there's a company called SPINS and Nielsen that track all of the POS data that's happening when you go shop. They keep track of all the scanned items and how many people are buying those items at Whole Foods, Walmarts Targets, like you name it, they keep track of it across the board in pretty much every non-salty snacking segment.

Let's call it a sweet snacking segment. The top SKU profile is always chocolate of some sort. So if you're having a cookie, the top SKU is chocolate chip cookie. If you're having a protein bar, it is a chocolate protein bar. And that just continues to help push chocolate forward because whether or not it's the direct snacking item or the commodity within the snack that's being eaten, pretty much in every top category, chocolate is present.

Turner: And it's just because it tastes so good. Why is it so prevalent?

Nick: It's the consumer's choice. People love chocolate. Let's say we forget health or not health and which chocolates are healthy and not healthy. There's a range of what chocolate is and the cheapness that you could produce chocolate at. So without commenting on that piece, Tte consumer in any shape or form is demanding chocolate.

Now, whether you as a producer give them cheap chocolate or real chocolate, or expensive chocolate, that's your prerogative. But the consumer basically seems to have voted that they want chocolate period. And how they take it, they'll end up deciding if they want cheap, good, or expensive.

Turner: a very frequent purchase gift around the year. If you think about Halloween, Valentine's Day, Easter – these are almost events that we've made up to sell chocolate or that we've built chocolate around them.

Nick: You nailed it. And so we saw a huge opportunity in chocolate being an everyday item. The interesting part about Midday Squares is – most of the chocolate companies bank on three days a year. Almost all the revenue happens on that Halloween portion, that Valentine's Day portion, or that Easter portion. I can't even tell you how much of the volume happens on those three days.

We're like, “Hey, we want to be an everyday item closer to a Starbucks and we want to position ourselves there” and so actually holidays are not where we get spikes. We're trying to say, how do we give you a chocolate bar that you can eat every single day and feel great about it?

Turner: Okay, so that's an interesting thread that we just kind of opened up. The idea for the company – I've heard you talk through this before, but let's pretend someone's not familiar with what you guys are doing at all. Can you explain how you came up with the idea and maybe walk through the first year so we can see how it all played out?

Nick: Yeah. My wife and I had always dreamt about building a big brand. We didn't quite know in what. Our whole lives, we've been chasing, building a massive brand of some sort.

Turner: When did you meet her?

Nick: I met her when I was 16 and she was 14, and we didn't start dating until we were 27. So we were close for many years before it became both a business and romantic partnership. But the reason why we were so close for so many years is we were the only people I think in our circles together that really were capable of dreaming at a level that was so big.

Believe it or not, when you're younger and you have big aspirations, it's hard to find people that really buy into them. A lot of people will brush you off. When she was 18, she was trying to build a hotel in Las Vegas, and whether or not she was capable of doing that, it doesn't matter.

All that matters is that for her, it was real and she was attempting to do it. And I was like, that makes sense. There was nothing in my mind that was like, “Why couldn't you do that?” even though we all know that the odds of doing that at 16 is very low probability.

We just never judged each other's dreams based on that and I think that's what made us really close. And then, I was part of a software company as the fourth employee. That company ended up having a liquidity event and I exited.

I had some time on my hands trying to figure out what I wanted to do next. She started a fashion company in New York and so I had written an angel check into that company.

Turner: As friends, kind of?

Nick: Correct. She needed money. I had come into some money and I believed in her as a horse, right? I was just like, no matter what this person does, I'm betting this horse.

Sure enough, that bet ended up leading to Midday Squares anyway so that's the beauty of it. When that clothing company didn't work out, she returned back to Montreal from New York. And during the process of us working together kind of on that project, we realized how much we enjoyed working together.

We wanted to build a food business and going back to my love for chocolate. It wasn't obvious. I'm going to give the audience kind of a spectrum. This is all 2016 and 2017 now.

During 2017, I'd come across a report talking about how massive the plant-based industry was growing, how big the real chocolate industry was growing, and how fast the refrigerated section of grocery stores were growing. The consumer was largely chosing fresh and refrigerated products over long shelf-life products.

Turner: Do you know why that's the case?

Nick: Yeah, a move to freshness. A hundred percent. The consumer is getting further and further away from being okay with their product living in a package for two years and being okay with why that is possible.

Turner: And is it a health thing? Is it a taste thing? Maybe both.

Nick: It's both for sure. One, what you could get from a taste perspective in being a fresh product is 10 times better than what you can get from trying to get something to last two years. And two, people are just more health conscious. People want to understand every single item on their ingredient deck.

And that's what we're tapping into. And so we just saw the massive opportunity to build an item that had the brand love of a company like Nike.

We didn't believe that it had been done in CPG yet in a category that was a commodity that was big enough to bring out the types of revenue that Nike could hit and in a channel that was differentiated from the current channel, and really try to build a company that gave Mars, Hershey, Nestle, Ferrero a run for their money in the categories that they were reaching consumers in. So we went for it.

Turner: Okay, so you had this idea. What was the order of operations or the next couple steps you kind of went through to make this happen?

Nick: So my wife was making a version of our brownie batter at the time. Like I said, we decided first that we wanted to create a food business, not necessarily sure what that business was going to be. The second thing was us deciding that it was going to be a product that filled this gap that I just spoke about. Third was my wife was making a product that already fit this gap. And so now we had to convert it into a product that was capable of being marketed and manufactured.

That’s when we had to decide on what price point we wanted to be on the shelves at a grocery store. And we also had to decide what was this thing that we wanted to sell to a consumer.

And for us, we wanted it to be plant-based, not because we wanted to be a plant-based company, but that's just where most of our dietary eating habits were going. We wanted it to be a very low sugar product, but we don't want to use artificial sugars because I just like regular sugar – I just like low sugar products. I don't need 30 grams of sugar. I just need 10 grams of sugar and I'm happy.

We wanted it to have high protein. We wanted it to be high in fiber, we wanted to digest well. And all these things were kind of what we put on a paper and we're like, now we gotta take your product that you're making and we gotta make it this.

We started hitting up universities. We ended up finding McGill University.

Turner: Is it in Montreal?

Nick: It's in Montreal. It's one of the premier universities. It's got one of the premier food science programs. Shout out Dr. Karboune she's the dean of food science there. She gave us the opportunity to work with McGill and we spent pretty much all 2017 developing the first iteration of Midday Squares that we want to take to market.

At this point, we were naive and we thought we were going to be able to get this manufactured. And we can get into the whole story of how we ended up having to manufacture this in our condo, but just to give the audience perspective, we didn't know that this wasn't going to be able to be manufactured.

You're told the story your whole life. When you listen to other brands, they contract and manufacture. You find somebody to make your product. And so being naive and green, we were like, “Hey, we're ready to go get this product manufactured. This is how we're going to do it.” And we were punched in the face with reality.

Turner: Really? What was that reality?

Nick: Well, The reality was that nobody wanted to make Midday Squares the way we wanted it to.

Turner: Why was that?

Nick: Because contract manufacturers are weird. You gotta remember there is a discrepancy in incentive. A manufacturer wants to do as little changeover in their plant as they're producing for customer to customer.

So the idea is, is that if you own a manufacturing plant, Turner, you don't want to have 50 products that you make with ultra customization, because every time you do something on your line that requires customization, you have downtime and you don't have efficiencies. In contract manufacturing, all your money is made on the pennies you're able to scratch out on volume and efficiencies. And you have limited warehouse space.

Okay, so let's say we come to you and you're already making chocolate and you're using palm kernel oil. I'm oversimplifying this example, but you're not really incentivized to have to bring in cocoa butter if Midday Squares wants to be the only person to use that on your line, because now you gotta find its own place in your warehouse. It's got all of the quality requirements that come with it.

And so anytime you as a small company start to add customization, you become a huge turnoff for contract manufacturers.

Turner: And you didn't even exist yet, right? Like you were a startup and you were trying to demand this stuff?

Nick: No sales. People were like, “Absolutely not. We are not doing this the way you want it.” The number two problem that we had is that the way Midday Squares is made is, it looks simple, but it's actually quite complicated in its form factor.

Everybody that knew how to make protein bars didn't know how to make chocolate. And everybody that knew how to make chocolate didn't know how to make protein bars. And Midday Squares is really like a combination of manufacturing practices of the two worlds.

It became this really complicated task. When we would get examples from contract manufacturers that were willing to give us potential samples of what they could make us, it didn't come close to what we wanted.

Midday Squares is all about form factor: double layer, stacked square. When you chew a Midday Squares, it's like a hard snap top to a soft bottom – two distinctive layers. Our chocolate layer, it's thick.

Now, believe it or not, that chocolate layer is extremely complicated to do, and the thickness and smoothness and all the things that we want it to be. So when they would give us examples, it would be this shitty little millimeter high chocolate, and we would be like, “Guys, no, this defeats the whole purpose of what we were trying to accomplish.”

Turner: It kind of reminds me of like a, like a peanut butter cup. It's got a thicker peanut butter layer with a thin layer of chocolate on the top, and then maybe on the bottom too. And again, it's probably like that's what they were set up to produce.

Nick: All the people that have come into the market to create bette-for-you chocolate, have just copied one of Hershey's, Nestle or Mars's products and just tried to change the ingredient deck.

For us, we wanted to own the form factor, the experience, and the name. So if I make a healthy Reese's Cup and I give it to you in the form of a Reese's Cup, it doesn't matter how much I do to convince you that it's not a Reese's Cup. In your brain, you're like, that’s a Reese's Cup. That's how great of a job Hershey's has done and owning that form factor.

And so we just didn't want to go towards those form factors. I think we're at a point right now that most people when blindfolded, if given a Midday Squares, they would recognize that it's a Midday Squares and nothing else.

Turner: It seems like the playbook for CPG - building your own manufacturing capabilities is not even something you consider, but building a unique form factor that requires its own manufacturing process is maybe a little bit more defensible because it's just harder to spin up.

Nick: There is a book written by this doctor who does all this research in building CPG brands. He's very active on LinkedIn. He wrote a book and in the explanation of building a true CPG brand at scale, he talks about this idea that we did by accident.

I won't try to say that we had this incredible foresight, but the concept that he proposes is that if you make something capable of being made on the current manufacturing infrastructure that exists at contract manufacturers – one, the probability of you have creating something unique is low, and two, everybody's going to be able to copy you very, very quickly.

And so that the only real true innovation exists on making a product that is actually incapable of being made on current manufacturing infrastructure. That's kind of his thesis. And I buy it because of what we're seeing at Midday Squares.

Turner: Yeah, and I kind of think of it too, if I were your contract manufacturer and I was making something for you, I get better margins by having higher volume. I'd be like, “Hey, other people come make it the exact same way.”

Nick: Correct. Oh the contract manufacturing industry is so dirty. I've been at conferences where people are literally selling me other people's IP. It's because that's how they get more volume, right?

You go to the table and it happens all very discreetly. They go, “Hey, so-and-so is making this here. We could do that. And it's selling like hotcakes.” That's the dirty secret of the contract manufacturing industry.

And so what's really interesting, if you look at the top companies – and I love studying them – Mars has never taught anybody how to make Mars Bar and Snickers. All of it, till this day, remains completely under Mars manufacturing facilities. They will never teach a contract manufacturer how to do it. And so I think that speaks volumes.

Number two is Coca-Cola never filed a patent on their formula because then it would have been public matter after a certain of time. They just said, screw it. We have more defensibility protecting our process and how we make it than actually a license or a patent to protect it on a public scale. So we think about that a lot at Midday Squares.

Turner: That's wild. I did not even think about that. Not filing a patent, because obviously you have to show people how you made it in order to have a patent.

Nick: It’s very common actually.

Turner: I think a lot of the startup advice you might get if you're building some kind of a physical product is number one, file a patent.

Nick: And let me ask you, how many of those people giving that advice have actually built a company? It's probably usually a lot of people that were backseat quarterbacks. That would be my bet. If you could find some founders that have gone from zero to let's say $500 million, that would have that same opinion, I would be curious to know.

Turner: So we actually have had a prior guest on the show that was one of his big things. I mean, he builds hardware. It's like internet of things, connected devices. Again it's, it's a valid thing to state and I think there's always nuance to it, but this makes a ton of sense in this case specifically.

Nick: Okay, so there's a flip side to that. I think on that debate, let's say we were having that live debate in hardware. It's very rare that you'll be able to control your end-to-end manufacturing and therefore at one point you have to disclose a lot of the internals regardless.

Turner: There are going to be different people for the chips, the assembly, like wiring things…

Nick: Yeah, most of it, and the finished product is most probably never going to happen on American soil or may happen. And so because there is such a strong industry around that type of IP and a lot of precedent around that IP in the court systems, I would say probably when it comes to electronic hardware, there's a strong argument to be made as to why IP is definitely worth considering.

Turner: And then in CPG, you probably can take all the raw materials or the inputs and basically just create it.

Nick: Nobody has to know. For most of food product, your supply chain is not like electronic. In electronics it's called a sub-assembly. So you'll have multiple sub-assemblies of raw materials.

Turner: That means like different factories, different places?

Nick: Chips, plastic molding, battery provider – on food, you're largely getting finished goods. Literally raw materials show up at our manufacturing facility and we convert the entire thing into a finished good. And so we're dealing with commodity raw material suppliers.

Turner: Okay. Did not think we'd go down this route, but that was, that was, that was crazy. Okay, so you figured out this whole contract manufacturing thing. How many did you talk to? Was it a couple or ten?

Nick: I think it was like 27. We started in the Canadian circuit, then we went to the US circuit. We were so desperate we even went to the European circuit and all of it was like nays, nays, nays.

There were a few that said, “Hey, why don't you invest $5 million in our plant and we could do this?” And then it was like well, if we're going to invest, 5 million in your plant and then we have to teach you how to make it, we should probably just do it ourselves.

Once we started to get to those conversations is when my wife really started to bring up, “I think we should build a manufacturing plant.” And I was actually, I was angry when she said that at first.

Turner: Because you were probably like, “That doesn't make any sense. That's not what you do.”

Nick: Are you crazy? We know nothing about manufacturing. This is not what I signed up for.

Turner: So were you live at that point? Like were you doing sales yet?

Nick: No. So I can tell you the craziness of how this all went down. So it’s summer of 2017. We started to get to an area where we're ready to launch and we have no fucking way to make this product. And so I'm on the circuit now doing some fundraising to potentially float the idea of us building a manufacturing plant.

We were getting rejected left right, and center, rightfully so. Why would anybody in their right mind give us money with no manufacturing experience to go build a plant? But we tried it anyways.

And then there was this real moment going into end of August where we looked at each other. At this point, we had brought on a third partner, my brother-in-law, who's a machine at building community and getting your brand out to the people. But we had all looked at each other and said, “It's time to either quit this idea or figure out how to get this done.”

And we had this – I'm not a religious person, but I'll just use it – this come to Jesus moment where Elon Musk was a big inspiration in the way that he kind of funded Tesla.[1]

[1] Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning were the original founders of Tesla. When they sought venture capital in January 2004, they raised $6.5M from Elon Musk in their $7.5M Series A and became chairman of the board of directors. A lawsuit settlement agreed to by Eberhard and Tesla in September 2009 allows all five (Eberhard, Tarpenning, Wright, Musk and Straubel) to call themselves co-founders.

And so we built a roadmap that was really simple. We’re going to build this really expensive product to convince people to buy into it so we could build a less expensive product to get more money to build an even less expensive product. And this is where we came up with the idea of: 1) price out what we believe we can do at scale of Midday Squares, so do the supply chain pricing based on scale, 2) build a roadmap of how we get to that scale, and 3) start manufacturing in our condo by hand and just assume that we're going to figure this whole roadmap out.

And that's what we did. In August 2018 when we officially launched, we went on Instagram and the whole idea was to combine Elon Musk, the Kardashians and Shark Tank into this one kind of storytelling style of showing entrepreneurship as it unfolds, really truthfully the whole thing.

From behind the scenes, we started shouting to the world that we were about to start this chocolate company with this crazy fucking idea of taking over the industry and building the next Hershey's. And we were going to do it in our condo. And we were going to figure out how to get from condo to massive manufacturing scale.

Turner: So you told people that like a factory was coming when you were just going live from your condo.

Nick: Yeah. We were like, there's no way to make this. Nobody's going to fund us, so we need sales to prove that people care about this. Once we have sales, then we can at least try to convince people to fund the roadmap of a manufacturing plant to get to scale, to make this an incredible business model.

Turner: So it was almost like crowdfunding in a way, but through people buying the product.

Nick: Yeah. But really using product market fit to convince true institutional investors to buy into the vision. This was the huge pitch: Midday Squares is a negative 14% gross margin company today, and we have a roadmap to get to 65%. This is how.

Our production cost based on our research is going to get here. And our material cost based on our research is going to get here. We can't get there unless we have a plan. So what do you need to see from us in order to give us the first couple of million to continue proving out the plan?

I think this is an incredible way to fundraise in steps when you're going after a big idea that requires a lot of belief in you as the entrepreneur, which is to set out a roadmap and kind of create a cadence structure.

And so the first check that we received, it was like we did a $2 million round with Boulder Food Group. The big hypothesis was, can Midday Squares continue to grow revenue at a a hundred percent? We got to a million dollars of revenue out of the condo in less than nine months.

Turner: And this was just like posting on Instagram, TikTok, and it was all through your own website?

Nick: No, it was even crazier. So we can get into that part. I don't want to confuse the fundraising with that part. Let me finish the piece on the fundraise and then we'll get into the actual, how did you go build this?

So the fundraise was like: fundraise one, take in a little bit of money and prove that we can create the blueprints for a manufacturing plant that actually would be capable of making Midday Squares while continuing to grow the product market fit, top line revenue of the business, and replicating the model outside of the province of Quebec in Canada. We'll return to this piece.

The second part was, “Hey, we have a blueprint. We're ready to make it. We did all this from a revenue growth standpoint. We've made all of this progress on production cost and input cost. Let's go build a plant.”

The third was, “Hey, we built a plant. It's working. Now we need to fundraise to start scaling the business.” And that's really, the three fundraises that we did. I'm happy to say for the listeners, Midday Squares, in less than five years, has been able to go from condo to a full-fledged, fully automated manufacturing plant that has above $70 million of output capacity. And we did it in those three steps.

Turner: That's amazing. Are you comfortable talking about – do you think you need to fundraise again? Are you guys in a position where you think you can self-fund?

Nick: It's interesting. All of the money of fundraising went to fund negative gross margin expansion. So essentially it was a chicken and egg problem. We had negative gross margin, which means every dollar was causing us to lose dollars. But you need the scale in order to get the plant running in order to achieve the gross margin that you need to be an incredible business in CPG, which is 65%.

People could debate me and I'd be happy to open lead debate on this subject matter. I think to build an incredible CPG business, your gross margin must be 65% so that's revenue minus discounts brings you net revenue. Net revenue minus cost of goods, out your door is 65%,

Turner: Raw materials and you count labor in there too.

Nick: Yeah. All of your labor costs, your utility cost involved in labor, like literally every function required to make a square must be in that COGS. After you deduct your net revenue from your COGS and divided by net revenue, if you're not at 65%. I don't think you could build the next Hershey's.

I'm not saying you can't build a company. I don't think you could build the next Hershey’s without that.

Turner: Okay. And then did part of that funding go towards actually paying to open the factory? I'm assuming that with all the manufacturing processes, it was probably expensive.

Nick: Yeah, but we were able to fund that all on debt. That was really interesting. So basically the strategy was that, in my opinion in general, I don't believe equity should ever go to funding capex because that's a debt function for me, and I think it's a poorer use of equity. That being said, you do what you gotta do to scale.

So really our equity dollars went to funding the discrepancy of gross margin as we expanded it, because we had no choice. So imagine when you're accelerating from $1 million to $3 million to $6 million, and this year we'll do $26 million. Our margin went from negative 14% to 7% to 16% and change, to twenties, to thirties. We're finally at 53%, still trying to get to 65%. You're hemorrhaging capital while you're doing that.

But now to answer your question, do we need to a fundraise. If we were doing another fundraise, it would probably be to expand quicker because we're actually at a point where the company's generating cash. We got there.

Turner: Amazing, congratulations!

Nick: Thank you. I appreciate that. The bank account hasn't gone down in six months. So our cash position from a free cash flow standpoint, we're at break even. And the gross margin has been the piece that's expanded everything to get our net revenue where it needs to be.

And so yeah, I think you saw it with Tesla as well too though, once they hit their scale, their gross margin expansion was like fast. And so I think there's an incredible opportunity to build incredibly difficult businesses that require this type of scaling model because of how few people are capable of doing it.

Turner: I think it's the only thing worth doing. Like I don't want to minimize or maximize what other people are doing, but it's like if you are trying to build a new company, you should probably do something hard and you should bring something new into the world, solve a problem, make people feel better in a different way, a new experience of some kind. It shouldn't be easy, it shouldn't be simple.

Nick: But it's 10 times harder. That's where I think a lot of people get deterred because there's moments of opportunities. And it will continue to happen. I believe there's always going to be fast money pump and dump startups. It will never go away. That is the feature. Not a bug.

That is the feature of great capitalism because at the end of the day, for every incredible breakthrough innovation, you're going to have a bunch of bullshit come through the door that's going to go up, down, confuse people into creating value that’s not real. And I don't think we should change that. I really don't. I think that's a feature of an incredible capital market.

What I do think is that the real riches that should drive true, big thinking capitalists out there. Things that are incredibly hard to make are incredibly hard, but provide incredibly value outcomes if you could pull them off.

Now I'm not saying that's a healthy choice, because there are great ways to make good money in life that don't take this tax on you. But I do think that for me at least, I want to try this once in my lifetime. I don't think I'll do it again in my lifetime.

Turner: Okay, so we covered the crazy ambitious fundraising, how you accomplish that to tackle a huge goal. Can we talk through the actual journey on the product, the company, the customer audience development building? So you were in your condo. How did you get the first couple customers and build the first couple products?

Nick: Yeah, so I think this is a great playbook for all CPG. It was stolen really from social software. So when you think about creating social products like Facebook, TikTok, Instagram, at least in the early days I would say, proved if you pump a lot of money into scale, you could get there if you have a great product.

But in the early days, you need to be resourceful. You go back to Facebook – it was like college by college launch. So we, we had the same idea. So rather than trying to create a CPG company in a North American scale of breaching to everybody on the internet that's in the United States or Canada, we chose to focus on our small market of Montreal.

And the reason that we did it this way is that the probability of somebody running into each other on the street, at a hairdresser, at a gym when you're marketing to somebody in Vancouver and somebody to Montreal, is very low probability, right? The landmass between them is like really, really, huge.

Turner: And Montreal is literally an island, right?

Nick: You could do the whole island in an hour with no traffic.

Turner: Okay. Is it 1 million? 2 million?

Nick: 2.3 million people, I think in the total Montreal. If you start to buzz in Montreal, every fucking person knows who you are.

Turner: So your strategy was literally take over an island, like that's how small you went.

Nick: Another thing was, we didn't want to use Facebook ads for the first million dollars because we had a belief that Facebook ads can create false positives from our experience. You can artificially trick yourself into thinking you have product market fit by buying the audience. And it could create a slippery slope of whether or not you have true product market fit.

So for us, it was can we get into grocery stores and can we turn on those grocery stores? Because let me tell you, a grocery store, if you are not providing value to the grocery store, they will kick you off in two minutes. So if you do not have real product market fit, you're going to find out real quickly.

Turner: Okay. So you've mentioned product market fit a couple times here. Can you explain how you think about that at Midday Squares? What does that mean for your product?

Nick: That the consumer wants to repurchase without very much reminder. So it's very, very obvious that they are returning and that they are making this a part of their staple. And it wasn't just a one-time wham bam. Thank you ma'am. That they are excited to talk about it. That they're excited to repost about, that they're excited to tell their friends about it. That to me is true product market fit.

If you tap a market where the largest source of your product marketing is word of mouth. To me, you've reached true product market fit. Now we can have debates on the spectrum, like what level constitutes product market fit, but I think a good rule of thumb is people screaming about your product more than you're telling them to scream about it is a good inclination that you're getting product market fit.

So how did we really calculate that? There was no real science. It was more art, but I can explain the art pretty in depth. One, we were so sure that our products deliciousness and what we were promising the consumer in terms of macros, meaning calories, proteins, fibers, sugar counts, was so epic. The deliciousness and the macros of it together would be a mind-blowing experience for the consumer based on what they're used to tasting in that category.

So we knew that we just needed to get it in people's mouths. What we did was we created a sample program. On our website, the sample program was 50 cents. Literally, you can buy one sample of Midday Squares for 50 cents, and we would get it to you.

And why we chose to do that was one, we want to get all the freebie people out of it, but we want to create social content. So we were recording everything at this point in time. We were waking up in the morning recording us doing manufacturing, telling the story of that.

Then we would get into our cars at 11:00 AM and we would go hand deliver all of the products to the consumers. And this is really out of Y Combinator's playbook, like when you're doing something early, do stuff that doesn't scale.

Turner: Yeah. That does not scale very well.

Nick: Yeah, this doesn't scale at all. That felt like a really good place to start. And so what happened was, for two months leading up to the launch, we were doing cryptic social media marketing with really cool stuff and food laboratories, chocolate testing. We were getting people hyped about what we were doing.

And let me tell you Turner, like we didn't have a big following. We're talking like 700 people each. But people were excited about what we were doing and so on the day of launch, we announced that you could get a sample on our website for 50 cents. And this shit just went crazy.

This is what happened. We would get an order for 50 cents. Then my brother-in-law and wife had this idea that we would create a customized Polaroid. Every morning we would dress up in funky outfits. We would take a Polaroid and we write a specific message to them. We would go make the hand delivery.

So in most parts, we were meeting the customer. We would film that content, post it on our social media. They were then excited about it. They would post it on their social media and it kind of went viral in our town. And it started going haywire. I'm telling you, it never stopped.

Basically, since that day till now, it's all been a blur and it's just been controlled chaos throughout to the point where pretty much all of our retailers have been demanded from our fan base that we've built through social media.

We never did a cold, explicit pitch to a retailer. And so that's how we got our retailers and everything. But we were starting with small coffee shops, anybody that was willing to give us a shot, and we did it in the island of Montreal only. We did a million bucks of revenue on Montreal island only.

Turner: That's gotta be almost scary. I'm just thinking about from a cashflow perspective – somebody gives you 50 cents and I'm assuming it costs you more than 50 cents in raw materials, but then you're also probably spending money on all the other things involved to get the product to them. So the faster it grows, the more money you lose.

Nick: Let me explain though, that program didn't last longer than three weeks. But we immediately put the full priced item on our website. And so it started to translate and we just kept on pushing the envelope. Eventually there was no sample program.

But for a full year we didn't stop the hand delivery. And so, it was really intense for 11 months. And I just think that's the dedication that's required to break through in CPG. I don't, think there's a way to do it that's much easier at this point in time.

Turner: Yeah, I think from what I've heard from friends who've similarly gotten into retailers of some kind, there's some element of social proof that's required typically, and whether it's pure social media, just being friends with the CEO of Target or whatever it is, like you need things to help you get in there.

Nick: Oh yeah. And then you need to perform. Getting in is just a small sliver of the equation. Then you need to perform on that shelf. And so we were just dedicated to performing.

I think when Boulder Food Group made the first investment in us, there was really two things that we needed to prove. By the end of the $2 million running out, we would have to achieve two things very clearly. One, can you get a blueprint to build a manufacturing plant? Two, can you replicate the success you had in Quebec outside of Quebec? And we chose Toronto as our second market and we ran the exact same playbook in Toronto and it worked.

Turner: So this first $2 million funding round, was this kind of after you took over Montreal or like during it?

Nick: No, a full year after.

Turner: Okay, so you hit a million dollars within nine months, you raised the $2 million bucks, and then you said, all right, we're doing Toronto next.

Nick: We had to move into a big kitchen. We didn't have a plant yet. But I think if you ask Dayton, who's our board member, investor, and dear friend, honestly, at this point in time, what was so convincing about Midday Squares throughout the journey was that we kept on making huge improvements on how we were building it.

My wife was a wizard during that time. We were creating efficiencies manually throughout the process. So there was new technology being introduced every 30 days so we could get more efficient in our output. We were figuring out full automation.

I think that was just really encouraging to everybody around the table, that it was not like status quo from beginning to end. Every 30 days, there was incremental evolution in how we were making Midday Squares.

Turner: So what's an example of that?

Nick: Okay. The trays we were using, custom trays that you could buy at stores, were only allowing us to output 32 squares. So we tested how big of a tray could we make? With a welder, that allowed us to get to 64 square output. Then the cutting process was becoming difficult. So we literally engineered a cutting device.

Just all these little tools along the way. How we were doing our batch processing and mixing. How we were doing the weighing Just nonstop. Iteration on efficiencies.

Turner: And it essentially just gives you a little bit more throughput, a little bit less waste, a little bit more output. So obviously margins slowly keep creeping up every week.

Nick: Correct.

Turner: Okay. And then so you had Toronto. Any crazy stories about the Toronto launch or was that pretty smooth?

Nick: Okay, so packaging was crazy. Packaging was the hardest point to scale Midday Squares because we were using these really pristine four pack pouches that we wanted for our price point. There was no easy way to do that.

Any way that we could have done that early on made the product look shitty and I can't even tell you how many times I would take a flight to Toronto, drive an hour and a half, fill suitcases with wrappers and have to fly back the same night in order to make production deliveries the next day.

The Toronto part created logistical pieces that were new for us. It created insane constraints. And then we were in these weird situations. There was like chicken and the eggs. So we wanted to launch a one SKU product. Why? Focus is everything in CPG, especially when you own your manufacturing component.

Turner: That’s the only way you're going to get scale and enough kind of margin on that one product.

Nick: Yeah, but guess what? No retailer distributor wants to list a one SKU product. They all want minimum three to four SKUs.

Turner: Why is that?

Nick: I don't know why. I think it's like this old kind of “just because” that's come through that makes it harder. Now we broke that norm, but that became crazy to convince people.

We were in a situation where Whole Foods wanted to launch us nationally, and no distributor in Canada wanted to hold us. And Whole Foods wouldn't launch us without a distributor. So it was consistent craziness like this nonstop. I could literally tell you stories till the end of time of just the chaos of manufacturing.

Turner: So you were doing these crazy trips between Toronto and Montreal in a day with packaging. Were you still working out of, your condo?

Nick: No, we were in a big shitty kitchen now, so we were in a commercial kitchen that had a little warehouse space. It was horrible conditions but it was better than the condo.

Turner: Okay.

Nick: And we had to still be following, for the record, since our condo, the Canadian Food Inspection agency's requirements. So we were being inspected throughout the whole time. You can create a food company outta your condo but you have to build a second kitchen, blah, blah, blah.

The sheer chaos of controlling your manufacturing brings in the whole new set of having to manage food safety. It was crazy. So we've been doing that as well the whole time.

Turner: So what happened after Toronto? Is that when you started to really think about, “Okay, we're going to make this factory,” or did you launch another city and you were doing a triangle trip with flying around?

Nick: No, we ended up doing a national launch in Canada. After Toronto, things were really picking up. COVID then hit so just to give you perspective, we had run out of money and we were financing the machinery. So at this point in time, we had to pay 25% of this whole factory and we would only get the output like in 24 months. So you have this huge capital expense that's early on.

We had all this money that was sitting on the line and production was getting to a point where we couldn't handle manual production anymore. People's bodies were breaking. There was significant, literally no joke, tendonitis happening in shoulders.

We were dealing with things and we desperately needed this machinery. COVID comes. Luckily our machinery was delivered to the new facility right before the world shut down.

Turner: Yeah, that would've been an absolute shit show. I can't even imagine.

Nick: I think it would've been the nail in the coffin for us. I actually don't think we would've made it back from that. But then, because a lot of our machinery is coming from outside of Canada, we couldn't get any of the engineers into the country to do the installation.

Turner: Wow.

Nick: And if we used any local engineers to do the installation, the machine companies were going to make the warranty void so we could not touch them. This created four months of the craziest chaos of our career so far to the point where I had to plead with the government on public television to get them to create special visas, to allow for these engineers to come into the country and actually do the installation so we can get the machinery up and running.

Turner: How did you make that happen? Like how did you get on national TV?

Nick: I think that's one of the big things about building out loud and being very public. We were developing relationships with journalists and television and radio hosts like when we were blowing up in Montreal. We have a huge fan base, a hometown fan base that's rooting for us to succeed on a global level.

And so we went back to the people that were covering our story and we told them the story and we're like, we need your help getting the story out there. Turner, I think you know better than anybody – building an audience and fan base is the dividends that will keep paying for the rest of your life.

Turner: It's super helpful. Just for context, for listeners, I have a portfolio company. Their Facebook ad account got cut off. We just talked about the reliance on Facebook and I tweeted about it. I have five people that all sprung in to help within less than an hour. And we're making progress. It's a pretty complicated issue.

Okay. So in terms of whole COVID thing, did you get engineers in to install all the equipment?

Nick: Yeah, and I'm telling this story because for anybody that's out there, that's an entrepreneur eating a shit sandwich right now. Just know this is what we get paid for as entrepreneurs. We get paid to deal with these shit sandwiches and ultimately it's how long could you stay in the pocket while feeling the pain? That’s where intelligence really has nothing to do with it. It's about that grit and pain threshold. It was just so painful.

Turner: What was your process for dealing with the pain? What advice would you give everyone?

Nick: We see a therapist every Tuesday. We see a founder therapist. We've been doing it as three founders. His name is Dr. James Gavin from the University of Concordia.

He specializes in management teams, executives, all this type of stuff. Deep psychological background as well too. Not just like business performance really. Psychological performance and then how we're communicating with each other. And we've been doing that every single day, every Tuesday for five years.

Sometimes we do three sessions a week where we'll do it as a founder group, then two of us will do it together, or one of us will do it alone. And it's been on our P&L, our investors have known about this. The company pays for it and it's religious.

We show up in good times and bad times. I think that's very key. A lot of people think to just show up in bad times. What you want is a muscle of where you're just doing it no matter what. Every single week, no matter what, whether you have nothing to talk about, all everything's hunky dory. Just keep on developing those dividends, to be paid in the future. And we just stuck to it.

A lot of therapy, a lot of feeling the pain and just accepting it. And then also giving yourself permission to quit, I think, is really important. It's just a reminder that nobody is putting a gun to our head to do this every day. And so this is all self-inflicted. And so how bad do you want this?

Turner: Did you ever want to quit?

Nick: So many times Turner. So many times. I still want to quit. I just had this like last week. I'm pretty exhausted and I'm just like, I don't know how much longer I could do this for. It's five years of intensity.

So here's our rule to solve for that second problem. Every September we have an alarm that goes off in our phone that says, do we still want to continue this journey? And if not, we have to, to come together as a founding team and understand what the next steps are.

If you really want to quit, you gotta take a month off first and only after a month off. If you still really want to quit, it's time to quit. And so I don't have an answer right now. As I speak to you, whether or not I want to continue doing this, I could tell you that pretty worn out and I don't know how much more I have in me.

Turner: Wow. So have you ever taken that month?

Nick: Not yet. Every two and a half months, I take a week off and that's my first litmus test. And I'm talking a real week off. People ask me, “What do you do during that week?”. I do nothing. I sleep for a week straight. I do nothing. I replenish. I recharge. I just do me, I walk, I do nothing.

I'm not trying to go and get more energy in the tank by doing X, Y, and Z. It’s to a point where if we do take a trip, of the 10 days that I'm off, I'm only on a trip for three days. That's it. So like my wife and I will go to Mexico for three days, or we'll go to Europe for three days, not more than that. Because I need to be sleeping for the whole time.

And based on how I feel after that, I decide. What I can tell you is every year it's gotten a little bit better. And we're very close to the point where we finally have an executive team that's supporting us. We're not fully there yet. We still have a few key team members to plug in.

I see the light at the end of the tunnel, but I'm also in the conundrum of I'm gassed. And so I have to just really decide how I feel. And uh, and, and that's an iterative process. The best advice I can give is never make hasty decisions and never make decisions while you're tired. Ever.

Turner: Did you guys make any mistakes when COVID hit? I'm assuming that was just a very up-and-down period for a company that relied on the internet and also in-person community.

Nick: I'm really proud about the way we handled COVID and our execution. We actually raised a round as COVID started to go on offense, and we launched the United States in COVID because we believed everybody was starting to play defensive. So I stand by the excitement of the move that we made there.

One of the biggest mistakes we made was underestimating. We used to be a two-square package and we changed the whole company to a one-square package.

We did a package change, a design change, and an ingredient deck change all at the same time. And we severely underestimated the destruction that would do to our supply chain. We almost bankrupted the company because of it.

We literally did a UPC change. So when you do a certain amount of changes on your package, you're forced to do a UPC change by the governing body of retail.

Turner: What is a UPC for people who don’t know?

Nick: It's the code that you scan your item for it to show up in the cash register at the grocery store.

Turner: So you had to change the barcode essentially.

Nick: Yeah. You can't run the same barcode when you make too many changes. They classify it as a completely new product.

Turner: And is, is that a big deal? It just changed the barcode.

Nick: Huge deal. But to your point, Turner, we felt the same way you did. This is not a big deal. We’re going from two squares to one square. We're doing a price change. We're doing an ingredient change. Like whatever. It's not the end of the world.

So why is this such a big deal? None of the supply chain infrastructure is sophisticated enough to take over the data that they have from your old UPC to your new UPC. So in your supply chain and distribution, you build up an incredible amount of data of when they do repurchases, how much should they be purchasing, when should they put in their purchases, how is the store purchasing?

So all this, what I call the wheel in motion data, didn't transfer over. We didn't understand that integrity. So basically you start completely fresh. And let me tell you, and I say this with love, the entire supply chain is not sophisticated when it comes to this industry.

I don't think any industry, to be honest, is that sophisticated. But the food industry specifically – it’s not a sophisticated supply chain, the people that are in it, number one, probably need 10 time more support than they even get from the companies that they're in.

And so when you make a fucking change and you go off the cliff, it's not like there are a hundred people ready to problem solve this problem. Everybody's in sheer utter chaos. And we saw our revenue decrease by 85% in the first month and shelves empty. Just nobody knew how to order.

And then this was the kicker that we screwed up on. We went and printed a UPC code on our new packaging that was too small to scan at the grocery store. So why is that a big deal if your product doesn't scan at the grocery store? The grocer is just going to input it as a grocery checkout, not as a Midday Squares checkout, and your inventory won't deduct from the system.

All these sales are going to start to go through and none of the data is going to flow upstream. So now not only did we do a fucking UPC change, which already destroyed the system, we screwed up on the UPC. And it took five months of us – like just honestly, I could throw up thinking about those five months – on calls and fixing.

Just the sheer chaos of that UPC changed my career. I don't think I will ever sign off on another UPC change at Midday Squares.

Turner: So I'm trying to get an understanding – when you talk about a UPC change with the supply chain, does that mean that you do not know when you're running out of certain raw materials or when you need to order more?

Nick: It's more your supply chain, so your distributors, not knowing how much to buy from you, on what cadence, the stores having no clue what to do. Then there's going to be a period where all the stores are going to have to do manual tag changes on the shelves.

What I can tell you is physics - the law of an object in motion stays in motion until it's reacted upon by an equal or opposite motion – is true. You do not want anything to change when you're on a shelf and everything's just flowing like clockwork. That means it's, finally set up. There's no human intervention that's required and you're in the flow of that grocery store, which is managing over 10,000 different products.

The second you have to do a UPC change, somebody has to go to your shelf, remove tags, remove the product – you're just disrupting a flow of purchasing that is not going to refine its flow in less than probably eight months.

Turner: So how big was the business at that point?

Nick: It was about $1.5 million a month, and we went all the way down to $400,000 months. And we had just in a fundraise and stocked the company for $2 million months. We had invested in an infrastructure of teammates. It was horrible.

Turner: I guess at least you did the fundraise to have some cash.

Nick: Yeah. We burned through it pretty quickly and had to do an emergency bridge round. That was the money largely that hasn't gone down that I told you about.

Here's what I'll say. It's not over until it's over. And if you just keep fighting, it's not easy to wake up every day and come do it. But if you keep fighting and you keep your eye on going one inch forward and communicating incredibly with your teammates and your investors, what will be will be. And in our case we survived.

Turner: Can you maybe talk us through just the tactical process of communicating and getting in front of a bridge round like that? Because I have a feeling that maybe something that a lot of founders are just curious to understand what it's like and how to do it.

Nick: So I think it is very important is to be ahead of everything with your investors, your board. So the goal is not to spring things on anybody last minute. That is like the worst thing you can do.

We immediately went back to the table, explained the problem, explained the potential implications of cashflow, and explained that there's a possibility that we're going to run out of money, before the chaos is done. And that way we may need to prepare to do a bridge round.

This happened like four months before the bridge round actually was executed and we were consistently reporting our cash position. One of our internal investors raised their hand and said, “We're in a position to do this.” And that allowed us confidence to know that we had a potential person on the rocks that was going to be able to do it.

But we were preparing as well, conversations with others in the event that we weren't going to get it from our existing investor base. I don't want to sit here and say that there was a perfect formula here – just a lot of luck in that the timing of our fundraise worked out that it was a new investor that had just come on that was ready for larger checks.

They had done a smaller check because we didn't want the money that they were willing to give us at the time. So that kind of put us in a interesting position to be able to ask for money because they had already wanted to give us more money. That's where I think luck comes into play.

But I think that the big takeaway is just get in front of it. You do not want people to find out last minute that something's going to hit the fan.

Turner: Yeah, that makes sense. As, I mean as an investor, I always appreciate understanding what's coming with my portfolio companies. You don't want to be overbearing, but you can help faster and more efficiently if you just know what's going on and you have visibility.

Nick: Correct.

Turner: How do you think about building tribalism around a product and building an enduring brand? Because it seems like you've done a very good job of that. Any just thought processes, advice, tactics for other people to kind of think through?

Nick: So my definition of true tribalism and brands that have it is you need to build fans and not customers and I have no secret sauce on how that's done other than this, though I do have a macro view on this. Why are creators having such, success building brands? The reason is that humans love following people less so brands.

But if you could bridge the human and a brand, it could live long past the human. What do I mean by that? Ben and Jerry haven't been with the brand since 1999, I believe, and Ben and Jerry's is still thriving, because the essence of the human has lived long on with the brand. And so I think in this day and age specifically, it is our job to create emotional connection with audiences.

That doesn't necessarily mean selling your product. And if you look at Kim Kardashian or Logan Paul or Mr. Beast or any of these people, they didn't build a brand first. They built an audience connection first, and then they plugged in a brand to the audience connection, and ultimately the audience shows up to watch them, not necessarily the brand.

And that really, I don't think, will ever change. Great stories build fans more so than functions build brands. When you look at Lululemon, there's almost this mystique around how they were built.

When the rumor becomes bigger than the story of how something happened, Goliath didn't have three arms, he had five arms. Or when people get to tell their own version of the mystique around how this thing got done, you're building fans and you accomplish that by entertaining.

In my belief, we always said it at Midday Squares, we act like a band and instead of selling records, we sell chocolate. And instead of going on tour and doing, musical acts, we do podcasts, we do speaking gigs, and we do this nonstop. That's how you build fans.

Turner: Yeah, that's fair. Hopefully you get some new fans out of this.

Nick: I'm pumped, man. I just appreciate you giving me the platform.

Turner: How do you build in public? That's related to this whole telling a story, and maybe the word build in public is actually the same thing as telling a story, but it's this word that a lot of people talk about.

What do you disclose? What do you share with people? What do you take as feedback? How do you process that?

Nick: Again, just my opinion on this subject matter is, everybody's gotta find their definition of how they're willing to do it. I think in our angle, we saw a huge opportunity that 90% of people in our position were unwilling to be truthful with the public.

Turner: Really?

Nick: Yeah, I really believe most CPG startups were unwilling to show the bad stuff that was happening to them. Machine breakdowns, product and quality problems, lawsuits, like all the shit sandwich that comes with it. There were very few that were willing to show it, and so we just felt that was our competitive edge. It was that we didn't care.

To show everything – that's something that's very comfortable to us. We shown therapy sessions where me and my wife are talking about divorce. That's how deeply we've uncovered that and that's our competitive advantage of how we do storytelling.

That being said, I don't think that's the only way to do it. I think what you do have to do is remember that humans are pretty selfish in what type of content they want to consume. And so you either have to add value, that's number one, or you have to give them entertainment or you have to give them reason to dream. Those are your three things.

In my opinion, that's like the most macro way to do it. And you have incredible people that have built a whole career in building in public, and by just providing value, right? Because maybe they feel, “Hey, I'm not charismatic. I don't relate well on camera. I don't find myself interesting, but I know a ton of incredible shit that could help people expand their lives.”

That’s a great way you could do all three. You could just provide entertainment which I think reality television has done really well. How many super intellectual people do I know that love watching trash TV? Why? It's just entertainment. They get to turn their brain off. But it still provides eyeballs and attraction.

So I think as long as you remember that your job is to compel an audience and no matter which channel you do it through, there are formulas to compel an audience, i.e. entertain, create value or inspire, You'll do just fine.

Turner: It all ties together when you think about it. Make people feel good, teach them something

Nick: Or entertain. Like why is so much of the music that's being played right now popular? Because it's giving people permission to be a little bit more ratchet.

Especially when you look into the hip-hop scene, and I see it on TikTok, you have incredibly well-put-together people wanting to expose their ratchet side. And so there's this genre of music that's giving people permission for 30 seconds to be either promiscuous, be more ratchet, or just do whatever the fuck it is that they want to do. And that's working incredibly well.

I think there are so many tricks to learn by just studying the music industry of what entertainment really means. And there are incredible tricks to learn from following people like yourselves and other people on Twitter of how they're adding value.

I study Elon, man. I study the way Elon plays his game. There's formulas to this stuff.

Turner: He's probably one of the best at it.

Nick: In his niche. There's other people better at other niches, but in his niche he's the best.

Turner: Oh, interesting. So what other niches or what other people doing it in different things, would you call out?

Nick: I think Kim Kardashian's a machine. She's hated by so many and misunderstood by so many, and I think she's just a brilliant machine that has been able to get herself to her heights by playing a game that makes a lot of sense to Kim Kardashian.

Elon's played a game that makes a lot of sense to our world. But Elon doesn't relate necessarily to a 22-year-old in college, per se, that is in a different area of life. Some he does. He's got fanboys. I'm a huge fanboy.

Then you have like Drake. Everything he's put together in the Drake package has been fundamentally chosen. Just follow him for the last 10 years. Everything from the clothing he started to wear, how he dresses himself, how he portrays himself, it has created that piece.

So for us, we do album cover photo shoots. We've done this forever. There's no reason why we should do album cover photo shoots, but if we portray ourselves in the light of that, we want to live in the cross section of fashion, rockstardom, and CPG.

If the consumer relates rockstardom to a specific thing, then if you do not show up to the consumer in that way, why would they ever relate you to that thing? And these are the tricks and games that you have to study in terms of how to communicate and build fans, in my opinion.

And you could do it in so many different ways. If you want the Tony Robbins crowd study, what Tony Robbins does. You're not going to find Drake fans by acting like Tony, you know what I'm saying? You have to decide who and what type of fans you want.

Turner: You tell the story that your fans want to hear.

Nick: All great copywriting is just regurgitating what somebody wants to hear.

Turner: Essentially yes. We probably have five minutes left before both of us have to jump. We're going to do a couple rapid fire questions.

First question, this is from Darryl Stone on Twitter. Are there any oompa loompas working in the Midday Squares factory?

Nick: So there's no real oompa loompas, but I think we have the most incredible team here. How about this? We have pipes that transport chocolate in the Midday Squares factory. So industrial pipes that look like you would find them in a wall of a building that have chocolate in them and if you tap them, chocolate comes out.

Turner: Wow. Is there a video of this online anywhere?

Nick: We don't post that type of stuff. But I bring my four-year-olds and seven-year-old nieces in. There's nothing like seeing a kid's face seeing chocolate come out of industrial piping because they don't expect that behind this thing is going to be chocolate.

Turner: Yeah, that's fair. Do you have a favorite interview question when you're hiring at Midday Squares?

Nick: Less of an interview question, but the process is actually quite important. We ask people to make a video pitch as their first interaction with Midday Squares. Why I love this so much is it fields out a bunch of people that believe they're too good to make videos at their stage of their career.

The video is actually less about the video and more about how you react to being asked to make a video. That's the real test. And I think it's an incredible tool that we use and I love it and it really funnels through the right candidate that's going to fit well in Midday Squares. I'm not saying it's for everybody, but I love that trick.